Paul

Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920)

Paul

Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920)In her recently published book The internet is broken. But we can fix it, Marleen Stikker, internet pioneer, philosopher, and co-founder and director of Amsterdam’s Waag institute for technology and society, relates an alternative history of the internet. She uses Angelus Novus by Paul Klee as a pivot and a symbol of how we deal with our history and future. Stikker quotes the essay by Walter Benjamin, who made this work by Klee world-famous:

A Klee painting named ‘Angelus Novus’ shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such a violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

— Walter Benjamin, On the Concept of History (1940)

Amidst this storm of progress, everyday life goes on as usual. You do the shopping, track down information for your thesis, make a date, keep in touch with your friends, book a holiday, check your grade for your last exam, transfer money, apply for a job, or arrange your tax affairs — who could have imagined that the internet would so rapidly become so all-embracing, so intertwined with every aspect of our daily lives?

David Bowie

in an interview with Jeremy Paxman in 1999

David Bowie

in an interview with Jeremy Paxman in 1999Someone who was quick to suspect that there might be more to this new medium than met the eye was the late rock star David Bowie. In an interview with BBC journalist Jeremy Paxman in 1999 about the nature of the internet, he says “I don’t think we’ve even seen the tip of the iceberg. I think the potential of what the internet is going to do to society, both good and bad, is unimaginable. I think we are actually on the cusp of something exhilarating and terrifying.”

Paxman, either playing devil’s advocate or perhaps truly naive, replies, “It’s just a tool though, isn’t it? It’s simply a different delivery system there. You are arguing about something more profound.” To which Bowie responds, “Oh yeah, I’m talking about the actual context and the state of content is going to be so different to anything that we can really envisage at the moment. Where the interplay between the user and the provider will be so in sympatico. It’s going to crush our ideas of what mediums are all about.”

With this somewhat abstract phrase, “the actual context and the state of the content,” Bowie hits the nail on the head — as we now know. The internet is not just a tool but has become an all-encompassing environment, closely interwoven with our physical world, and virtually no one can afford to live without it anymore. In the words of Marleen Stikker: “The internet today is much more than a couple of news apps on your phone, a weather app, your email and social media — it is the digital superglue that connects devices to each other, and people to their devices.”

The fact that the internet has embedded itself so deeply in our lives, and has become such an inherent and necessary part of our society, raises a painful question: who does it actually belong to? Well, we now know that the internet doesn’t belong to us, its users, but to the “big five”: Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft, Facebook, and Amazon — companies with a combined value of over 3.3 trillion dollars and more than 40% of the Nasdaq 100 index. As Shoshana Zuboff points out in her book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, we are their capital—as mentioned before in this post: the data we leave behind us by living our lives is collected and sold to the highest bidder.

‘The

Internet is broken. But we can fix it’, published to mark the 25th anniversary of the Waag

institute for technology and society

‘The

Internet is broken. But we can fix it’, published to mark the 25th anniversary of the Waag

institute for technology and societyIn her book — as yet only in Dutch — Stikker discusses every aspect of this issue of the marketisation of our existence. She leads the reader through an alternative narrative on the origin of the internet, via the early years in Amsterdam, the freenet De Digitale Stad (“The Digital City”), hacker parties, discussions about net neutrality, phreaking & lock picking, mailing lists, transhumanists, and techno-optimists. She talks about the role of government, citing The Entrepreneurial State by Mariana Mazzucato to debunk the myth that it is the market that generates major innovations. Stikker also explores the interconnection of ecological and technological problems. But she also offers solutions: a series of related approaches and methods for us to develop over the next 25 years.

The way to create a different internet, Stikker says, is through “active citizenship”: the realization that technology is never neutral, and that there is always intention in design. This is why it’s so important not to wait until a technology has already arrived before you make up your mind about it, but to think ahead about the technologies to be developed. To do this, interdisciplinary collaboration between artists, scientists and citizens is crucial, because together they can reflect on the triangle of art/technology, society, and the future.

The development of algorithms and software is a case in point. This is generally left to developers and takes place behind closed doors, which is not only troubling but also unfair because the questions they have to deal with affect us all.

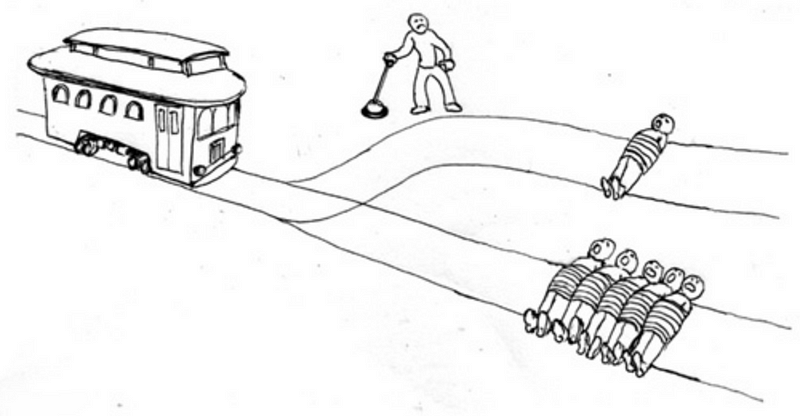

Philippa

Foot’s trolley problem

Philippa

Foot’s trolley problemTake the example of self-driving cars. Philippa Foot’s trolley problem neatly captures the dilemma. In the scenario she describes, a person has to decide in a fraction of a second whether or not to pull a lever. Should they leave the trolley to continue along the track and run over five people, or intervene by switching it to a different track, thus killing only one person? What if one of the people on the rails is a loved one or a family member? Or very young? Or very old?

Embedding this kind of decision-making in software is a virtually impossible task. It also makes clear that we have to recognize that the choices we make are not always objective, but are based on assumptions, as Stikker explains: “Anyone who collects data or writes software makes choices. You don’t have to apologize for it. You are only human. But you do have to recognize that your choices are not objective, and question your own presuppositions.”

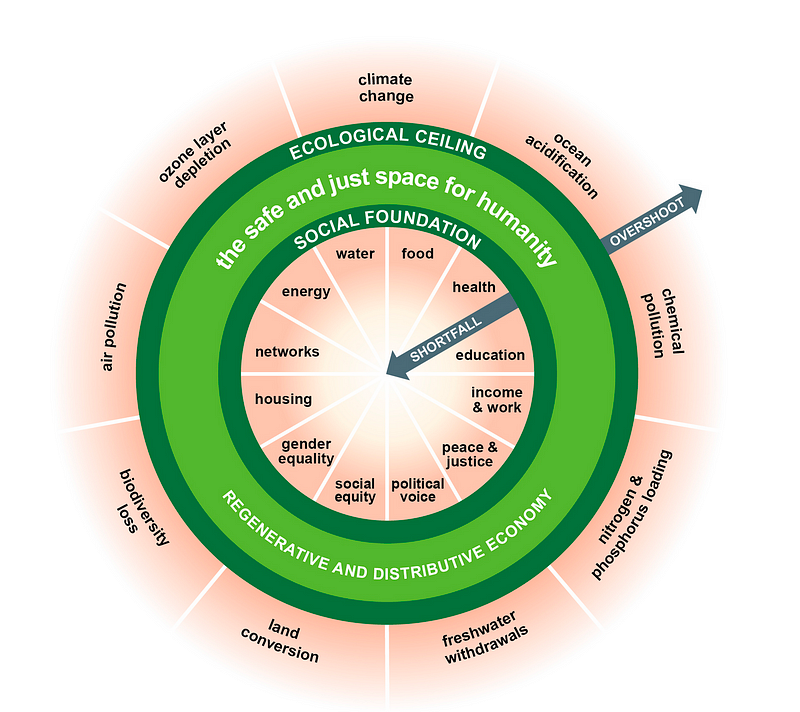

Donut

Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist Kate Raworth (2017)

Donut

Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist Kate Raworth (2017)

A second route to fixing the internet that Stikker explores is explained in the 2017 bestseller by Kate Raworth, Donut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist. Raworth places “the safe and just space for humanity” between two concentric circles. The outer circle is the environmental ceiling, and the inner circle is the social foundation. The basic principle is that economic activity should be “regenerative” and not “extractive.” This means that the capacity for recovery must be central, and profits should not be made at the expense of exhausting the system, as this is unsustainable. If we view the internet from the perspective of this model, very different choices would need to be made.

Open

Thursday at Fablab Waag, Amsterdam

Open

Thursday at Fablab Waag, AmsterdamA third point that Stikker makes relates to the power of creative culture: the idea that citizens and social organizations should be involved in designing technologies. Here interdisciplinarity and inclusiveness are central. Stikker cites the example of what she describes as “making-places” — manufacturing workshops where participants pose questions about technology — and “policy labs,” in which residents help to design new local government policy. The methods applied in these kinds of places center on design-oriented and artistic research, co-creation and prototyping: “As long as it takes place in an interdisciplinary group and ‘ordinary people’ — citizens or consumers — can participate.” To make a difference, Stikker says, society will ultimately have to appropriate technology. People will have to roll up their sleeves. We have to learn to tinker digitally, open black boxes, and also question our own assumptions.

The Art of

Tinkering by Karen Wilkinson and Mike Petrich (2014)

The Art of

Tinkering by Karen Wilkinson and Mike Petrich (2014)Stikker is not alone in her vision; there is a growing awareness that the world can and must change. Twenty-five years after the launch of De Digitale Stad, a new initiative has emerged: PublicSpaces, a coalition of around 20 Dutch public and cultural organizations including the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA), public broadcaster VPRO, Netherlands Film Festival (NFF) and Eye Filmmuseum, which is again trying to develop digital public space on the internet.

Ex-Mozfest Wrangler Ian Forester and hacker and pundit Bill Thompson are working on PublicSpaces on behalf of BBC R&D as a European partner, based on a belief in the possibility of an alternative internet. They are joined by people like Rachel Coldicutt, who at the last Mozhouse in London made an impassioned plea for “Just enough Internet” — an inspiring example of a fresh, new story. (“What is Netflix’s most important competitor? Dinner with friends or enjoying a glass of wine with your partner.”)

The book The Art of Tinkering offers a clear and accessible vision of an inclusive creative culture in which artists serve as inspiration. And indeed, the entire program at Waag itself is devoted to exploring the social and cultural impact of new technologies based on the values of openness, fairness, and inclusivity.

In short, it’s time to exchange our role as passive consumers for that of active villagers and townspeople — to shape the future together. All that needs to happen is to restrict the activities of monopolists such as Google and Amazon because otherwise any form of competition will ultimately be outweighed by big business. This is clearly a task for European legislators. But there is hope, says Stikker, in her conclusion:

“Twenty-five years ago the internet was still a greenfield. After years of a neoliberal tech bubble that caused it to wither into a brownfield, the wind has now changed, and a new, fresh breeze is blowing. Klee’s angel, hurled into the future with his eyes on the past, can finally turn around and shift his gaze to the future. There he sees new, green fields. Because everything we need to fix the internet is already within reach.”

This is number 5 in the Our Brave New World series produced in the context of the Creative Economy theme of the Fontys University of Applied Sciences in Eindhoven, in collaboration with the Amsterdam-based design studio ARK.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.