Can virtual reality increase pro-social behaviour and reduce prejudice?

by Dr. Harry Farmer

The past five years have seen an explosion in both the technical capability and the affordability of virtual reality (VR) headsets which has enabled VR to spread outside of the lab into consumer environments. This progress has been accompanied by an increased interest in the use of VR as a means of conveying narrative including nonfiction narratives. For the past two years the Virtual Realities: Immersive Documentary Encounters project has been examining the production process for, and audience reactions to, this new field of virtual reality nonfiction (VRNF). Research by our team has found that between 2014 and 2017 the amount of virtual reality nonfiction content being released increased from 10 to 181 pieces and this increase in content seems set to continue with VRNF now an established feature of many film and documentary festivals.

A significant influence on the development of VRNF can be summed up by Here be Dragons/Within CEO Chris Milk’s description of VR as “the ultimate empathy machine” in his 2015 TED talk. This idea suggests that by giving us a sense of presence, the feeling of being spatially transported to the middle of a scene, VR can induce in the viewer a greater sense of identification with, and empathy for, the people being observed than traditional formats. The term empathy is commonly used but often vaguely defined. Within cognitive science it is commonly defined as the ability to share and understand the experiences of others. However, in common usage the term is often expanded to include related concepts such as sympathy and compassion and seen as the cause behind positive social behaviours and decreased stereotyping and discrimination towards marginalised groups. The idea that VR could provide a powerful new medium for boosting empathy and pro-social behaviours was a common theme among many early adopters of VR in nonfiction.

It is worth noting that the idea that novel technology and art can be used to drive changes in social attitudes is not a new one. Literature has long been held up as a powerful means of putting ourselves in another’s shoes. Indeed, thinkers such as Stephen Pinker and Lynn Hunt have linked the rise of the popular novel in the late 18th century to an increased acceptance of the ideas of basic human rights. For example, novels like Uncle Tom’s Cabin and autobiographical accounts of the experiences of enslaved Africans such as those of Olaudah Equiano and Fredrick Douglass have been credited with playing an important role in the growth of the abolitionist movements in Britain and the United States.

Similar claims have also been made of traditional 2D films. The phrase “empathy machine” was first used by the film critic Roger Ebert to describe the power of cinema to allow the viewer to “understand a little bit more about what it’s like to be a different gender, a different race, a different age, a different economic class, a different nationality, a different profession, different hopes, aspirations, dreams and fears.” These examples situate claims about VR’s ability change our social attitudes as continuing a well-trodden path regarding the role of art and media in granting us insight into the lives of others.

However, the value of nonfiction VR as a means of producing empathy has been criticised on a number of grounds. One objection raised by Kate Nash critiques the idea of VRNF as an empathy machine by claiming that the concept promotes an “improper distance” between subject and viewer. In her 2018 paper Nash argues that VRNF can only ever offer a superficial, imagined encounter with another person. She further argues that, in suggesting that such encounters can offer a deep understanding into the experiences of others, VRNF creators risk trivialising the suffering of others while fetishising our own responses to that suffering.

Others, like the social psychologist Paul Bloom, have questioned whether focusing on empathy is a desirable goal in the first place. Bloom argues that viewing empathy as the foundation of moral interactions leaves our behaviour prey to a host of cognitive distortions. For example, we tend to feel more empathy towards specific individuals rather than larger groups and to those whose behaviour we view as deserving, as opposed to those who violate our social norms, e.g. being more empathetic to those who contract HIV due to a blood transfusion compared to those who contract it due to heroin use. If Bloom’s analysis is correct, it is possible that, while VRNF may boost empathy towards the specific individuals depicted, this boost will not necessarily transfer into more compassionate behaviour towards the larger groups to which they belong.

Along with these theoretical issues there are also practical issues with examining the power of VRNF to boost empathy. One particularly strong one is the lack of any agreed way to measure empathy using an implicit task. Instead, researchers have tended to use self-report measures which are open to what psychologists term “demand characteristics,” or the desire to respond in the way they believe the experimenters want them to rather than reporting what they actually feel.

Motivated by these issues with the “pure” measurement of empathy, we decided to focus instead on the question of how far VR could affect wider social attitudes and behaviour. Specifically, we sought to examine how exposure to the VRNF piece “Clouds Over Sidra,” directed by Chris Milk, which depicts the life of Sidra a 13-year-old Syrian girl living in the Za’atari refugee camp in Jordan, affected prejudice towards Arab people. The question of whether VR can reduce prejudice is particularly important give the rise in Islamophobic and anti-Arab sentiment that exists in Western society. This has been most graphically illustrated by far-right attacks such the Christchurch massacre in New Zealand and, in the UK, the attack on worshippers at the Finsbury Park mosque in London, but also in the rise of anti-immigrant parties and rhetoric across the West in the wake of the decades long “War on Terror” and the more recent Mediterranean migrant crisis. In this context VRNF could potentially be a useful tool in challenging such negative prejudices and attitudes.

Image from

the virtual reality documentary Clouds Over Sidra, by Chris Milk for the U.N. (Credit:

Within/U.N.)

Image from

the virtual reality documentary Clouds Over Sidra, by Chris Milk for the U.N. (Credit:

Within/U.N.)Our Research

To examine these issues, our team conducted a lab study in which we modulated two affordances of 360° VRNF, immersion and agency. By immersion we mean the extent to which the viewer is fully immersed in the visual scene. High immersion occurs in situations where the scene fills the viewer’s entire visual field, such as when wearing a head-mounted display, in our case an Oculus Rift headset, Low immersion refers to viewing the scene on a more traditional flat-screen device, in our case a Samsung Tablet. By agency we referred to the extent to which the viewer had control of where in the scene they could look. Thus, for us, high agency would be the original 360° video format, while low agency was a “director’s cut” of the video with a fixed view in each scene.

Participant

in our full virtual reality condition.

Participant

in our full virtual reality condition.The combination of these two affordances of VR produced four different viewing conditions: high immersion and high agency, in which people watched in a headset and controlled their viewpoint via head movements (a “full” VR experience); high immersion and low agency in which viewers used the headset but their view was fixed and did not change with their head movements; low immersion and high agency, in which people viewed the documentary using a Samsung tablet with a custom-built “magic window” app which changed the scene based how they moved and tilted the tablet in space; and, finally, low immersion and low agency, where people watched the documentary on the tablet with a fixed view in a similar manner to a traditional, non-VR film. We tested 32 participants in each of these conditions, giving us a total sample of 132 participants.

We assessed the effects of watching the documentary in different conditions on prejudice using two different measures. The first was an explicit questionnaire measuring subtle prejudice towards Arabs and Muslims more generally. Importantly, we also measured implicit attitudes towards Arabs using a novel version of the implicit association test (IAT). This test is designed to reveal people’s unconscious associations between concepts in different categories by comparing how rapidly they can categorise these concepts when paired (for a demo, visit the Project IMPLICIT website). In our version of the IAT, we had participants (all of whom identified as having a European background) categorise photos of Arab and Wfaces and positive and negative words. If people responded faster when they had to press the same button for White faces and positive words and the other button for Arab faces and negative words we classified them has having a preference for white? Europeans. In contrast, we classified people as having a preference for Arabs if they responded faster when they had to press the same button for Arab faces and positive words and the other button for European faces and negative words.

Our final set of measures sought to investigate whether any change in empathy or prejudice caused by our VR intervention also led to meaningful changes in behaviour. To measure this, we gave our participants information about a charity run by Syrian refugees and gave them the option to donate any amount from £0-£10 of their payment from the study towards the charity. To further test their commitment to the charity we also asked participants if they wished to subscribe to the charities email address, an action which had a potential cost in terms of receiving emails from the charity in the future.

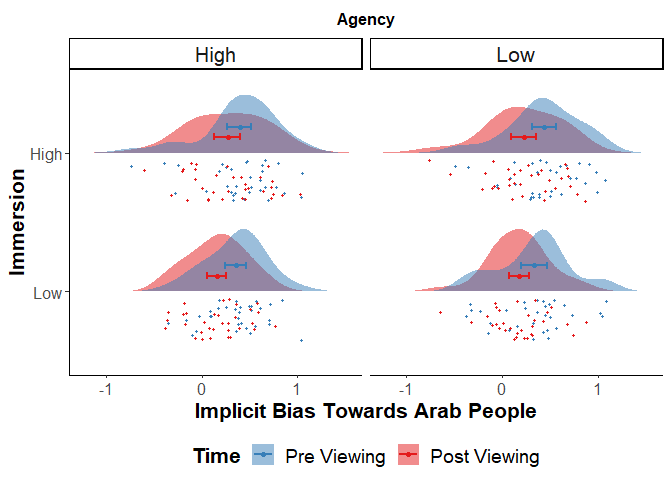

To look at the effect of VR on implicit and explicit prejudice we analysed differences in our measures between the four groups at two measurement points (pre- and post-viewing) as the key factors. For the self-report measure our data showed that there were no significant differences between our four groups, and reported levels of subtle prejudice did not change over time, suggesting that viewing the documentary in any format had no effect on participant’s’ self-reported levels of prejudice. When examining the results of the IAT measure we found a main effect of time with participants showing a lower score (less bias against Arabs) after watching the documentary compared to their pre-test scores. However, this pattern was the same across all four conditions, suggesting that the manner in which the documentary was watched was not important for the amount of prejudice change reports.

Raincloud

Plot showing implicit bias pre and post viewing the documentary. Further right indicates increased

bias against Arab people. Clouds show distribution and raindrops show individual participants. Solid

dots indicate means and error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Raincloud

Plot showing implicit bias pre and post viewing the documentary. Further right indicates increased

bias against Arab people. Clouds show distribution and raindrops show individual participants. Solid

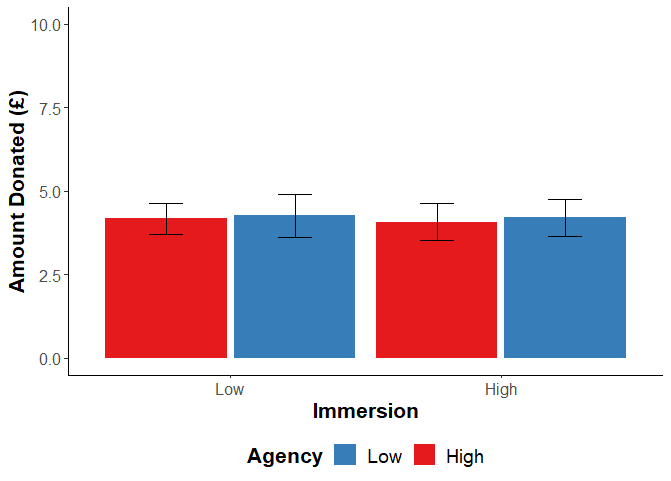

dots indicate means and error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.Finally, we examined the extent to which viewing conditions affected pro-social behaviour as measured by donations to a charity for Syrian refugees and tendency to subscribe to the charity’s newsletter. For both these measures, however, the results were similar to those for prejudice. While our participants did tend to donate money to the charity — with an average donation rate of £4 — the amount donated did not significantly differ between our conditions, nor did the rate of newsletter subscriptions, which was approximately 30% in all four conditions.

Amount

donated to charity in each condition. As can be seen the amount was totally uneffected by condition.

Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Amount

donated to charity in each condition. As can be seen the amount was totally uneffected by condition.

Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.Implications and Caveats

Did our findings support the idea of virtual reality as the “ultimate empathy machine”? Overall, the answer appears to be no. In general our results suggest that the use of 360° VR as a medium for content delivery has no greater effect in reducing prejudice, or promoting pro-social behaviours than more traditional forms of media. While this outcome could be seen as disappointing for content producers who feel that VR offers an opportunity to change social attitudes to an extent not seen in other mediums I will conclude this piece by giving some brief caveats to our research and thoughts on what forms of VR content might prove more effective for this goal.

The first thing to note is that while we did not find any strong evidence that the medium through which content is experienced could alter either explicit attitudes or implicit associations that does not mean that “Clouds Over Sidra” has no effect on viewser. In fact, we found that viewing the documentary in any format led to an immediate reduction in implicit bias against Arab people, suggesting that while the idea of VR as an ultimate empathy machine may, in this case, be overblown, there is support for Ebert’s original idea of film as a tool capable of bringing people together. The other key caveat to take from our research is that while 360 video is currently still the most common format of VRNF, largely due to its greater accessibility to content creators coming from traditional film backgrounds, it only scratches the surface of the potential uses of VR as a means of conveying narratives. There is considerable research suggesting that more immersive forms of VR, particularly those that give the viewer the sense of being embodied, i.e. by being able to feel or control the body of someone from a different ethnicity, gender or other identity, may be more effective in changing attitudes than this more basic form of virtual reality we examined in our study.

The challenge for VRNF producers to consider as technological progression expands the capabilities of VR is how to avoid falling into two key traps. The first of these is the trap of improper distance highlighted by Nash. Her argument that VRNF can risk becoming a form of experience tourism is even stronger when considering experiences which don’t merely seek give us the feeling of being transported to the same location as a distant other but actually the sense of being that other. The second issue is the question of how far any VR experience that allows the user to actually interact with the world they are present in can be considered to be nonfictional. By definition, allowing the user to interact with the environment in a way that can affect the scene blurs the boundary between an accurate recounting of an event or experience and the creation of a fantasy narrative. Thus to the extent that nonfiction documentary relies on a claim to be depicting “the real”, the adoption of interactive VR in nonfiction means moving away from the idea of documentary as replaying “real” events and a move towards seeing VRNF as a means of creating “real” experiences, even at the cost of the accuracy of those experiences.

Despite these challenges and considerations, however, there is already evidence that VR producers are rising to meet them. Jane Gauntlet’s Dancing With Myself, which aims to give users a sense of her experience in the lead-up and aftermath of an epileptic seizure, provides a nice example of an attempt to share experiences through embodied VR handled with care and sensitivity. Meanwhile, pieces that merge some aspects of traditional documentary, such as verite sound recordings, while allowing the user to freely explore a visual space (the BBC’s Easter Rising or Notes on Blindness: Into Darkness) may point the way towards giving users a an experience grounded in historical reality while making the most of the interactive abilities that VR can produce. It seems likely that future producers of VRNF content will be able to build on the work of these early pioneers to develop a new and powerful grammar of VRNF.

This article is part of Virtual Realities, an Immerse series by researchers on the UK EPSRC funded Virtual Realities; Immersive Documentary Encounters project. This project is employing an interdisciplinary approach to examining the production and user experience of nonfiction virtual reality content. The project team is led by Professor Ki Cater (University of Bristol), Professor Danaë Stanton Fraser (University of Bath) and Professor Mandy Rose (University of the West of England) with researchers Dr. Chris Bevan, Dr. Harry Farmer and Dr. David Green and administrative support from Jo Gildersleve. For more information see http://vrdocumentaryencounters.co.uk/

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.