Image by

Keira Heu-Jwyn Chang

Image by

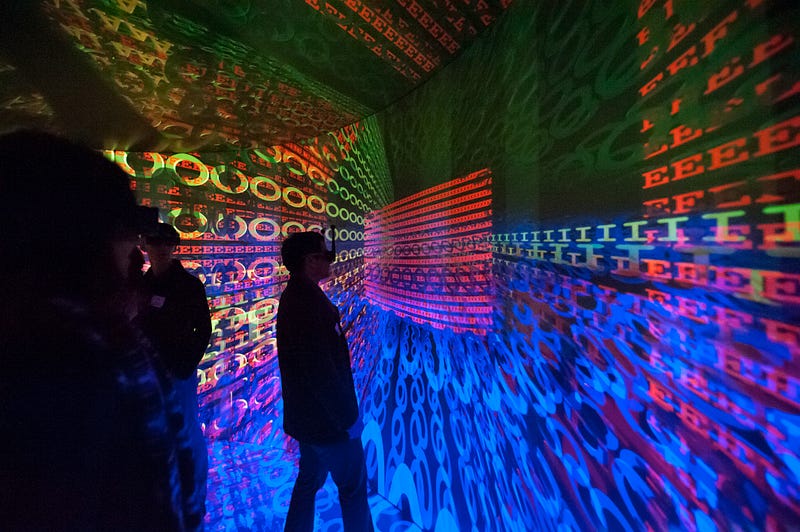

Keira Heu-Jwyn ChangIn the months before the Apple Watch was released, nerds around the world (myself included) slow-motion scrubbed through ads to Kremlinologize the device’s anticipated functionality. One video seemed to feature animations of hand gestures — a thumbs up and a thumbs down — which I interpreted to mean that the bundle of optoelectronic, gyroscopic, and accelerometric sensors Apple was calling a “watch” could read and interpret a user’s hand gestures.

I found myself wondering what programmer in which sub-basement at Apple got to decide what a thumbs up or down meant. How were those gestures captured in data? Did each gesture have its own spec? How would Apple localize movement? What assumptions regarding users’ ability, local culture, gestural semantics, and skin pigmentation were required to discern user intentionality? How, ultimately, did Apple choreograph the interface of this device, and how would it, in turn, choreograph us?

I was teaching dance history at Harvard when the Watch was released, a fact I recall here because it happened a few weeks before one of our students, Aran Khanna, got very publicly fired from his internship at Facebook. Khanna had created a browser extension that scraped geolocation data from Facebook Messenger to make a “Marauders Map” enabling users to see friends’ realtime locations. There wasn’t an obvious way to prevent others from accessing the data, and more alarming still was Facebook’s apparent ability to log geospatial coordinates with neither users’ knowledge nor consent. I learned about the breach, fittingly, from my Facebook feed while across the street from Mark Zuckerburg’s former dormitory. Walking to seminar that day, I became fixated on the possible inferences that could be made on the basis of indexable location data. What patterns of life could be discerned from an individual’s (or two billion individuals’) movements across space and time?

I should note that I’m a choreographer. My dances have been performed on stages around the country, and I am an expert in how bodies create meaning through movement. Up until the 2015 release of the Apple Watch and the Mauraders Map, my engrained understanding was that choreography was a thing for trained bodies to perform on stages in front of people. I’d never contemplated choreographed bodies performing for audiences of machines, let alone algorithms. At this point, there was no obvious group to work through this with. There was no trade association, no membership organization, no books or pamphlets. Yet, more instances of choreographic interfacing between bodies and surveillant technologies cropped up daily.

It was around this time I became aware of how government intelligence entities use global positioning satellites, cell tower triangulation, and voice/speaker recognition to track bodies through real and virtual space. One top secret NSA program revealed by Edward Snowden (codenamed: CO-TRAVELER) juxtaposed the accumulated cell location data of known persons of interest against anyone else whose data had been previously collected. On this basis, the NSA was able to algorithmically hypothesize relationships between previously unrelated actors on the basis of shared movement patterns, (i.e. co-traveling). The resulting meta-data were stored in a vast digital archive called FASCIA, which, not coincidentally, is the anatomical term for the literally connective tissue that holds organs and muscles together. This body of data (or “Body of Secrets,” per journalist James Bamford) was in the service of what internal NSA memos describe as “all about locating, tracking, and maintaining continuity on individuals across space and time.”

It sounded like choreography to me. Whether it’s people existing under surveillance capitalism, within a national security apparatus or performing in a dance show, we’re ultimately talking about the observation, interpretation and meaning-making of bodies in motion. It’s just that these four components (observation, interpretation, meaning-making, bodies in motion) used to be done exclusively by humans. Now, they are all increasingly accomplished by machines.

I spent most of 2015 obsessed with the relationship between bodies and surveillance, but lacked obvious means to validate concerns for what I saw as a potential human/computer interface cluster$@*&. In the Venn diagram of choreography and surveillance I was the only nerd I knew in the overlap, so I started talking to folks with backgrounds in technology and performance, if not surveillance and choreography specifically.

I recall early discussions with software consultant, composer, and philanthropoid Kevin Clark, who pointed out the lack of stable classifiers for gesture and consequent absence of a Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) for movement. This led to a conversation with composer Stephan Moore, who had done sound design and tech for the late Merce Cunningham, and was completing a PhD in Computer Music and Multimedia Composition at Brown. He shared my interest in a potential reframing of choreography relative to emerging technologies, and volunteered his living room (and liquor cabinet) to facilitate future ad hoc gaggles.

I took him at his word, and later that month my longtime dance colleague, Keira Chang, rented a van and picked up nearly a dozen art nerds from around New York City and brought them to Moore’s Rhode Island living room. The group notably included Catie Cuan (now pursuing a PhD in choreography and robotics at Stanford), Victoria Nece (now a Senior Product Manager of Motion Graphics and Visual Effects at Adobe), dancer / choreographers Kristen Bell and Jordan Isadore, Moore, Clark, and a handful of others working across art and industry. Sitting on Moore’s couch, I recited my premises and concerns: are body-sensing technologies as potentially problematic as they seem? Could artistic practice broadly — and choreographic practice specifically — be a means to work through such issues? The conclusion of the group was a resounding yes.

A few months later, scholar Simone Browne published the brilliant “Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness,” a horrific genealogy of surveillance technologies and their tendency to reiterate (and, indeed, scale) violent bias. Through Browne I learned of other badass theorists — Lisa Nakamura, Shoshana Magnet, Kiri Miller, and Wendy Chun — who explored embodiment under surveillance as a function of race and ethnicity, and who made explicit the corporeal risks of historical and emergent technologies.

The stakes of choreographic engagement for bodies under surveillance was becoming more clear, and the rolodex of individuals wanting to work on the discourse was growing. We couldn’t find any extant convenings on the subject that foregrounded artistic research and had an explicitly anti-racist ethos, so we founded our own.

Since 2015, I have worked alongside (my now colleague at Brown) Miller, Clark and burgeoning live arts producer Ariane Michaud to produce the Conference for Research on Choreographic Interfaces (CRCI). It is dedicated it to questions of choreography and surveillance and operates with the belief that addressing such questions requires wildly diverse, intimidatingly heterogeneous expertise from culture critics, theorists, computer scientists, dancers, anthropologists, ethnographers, poets, improvisers, and podcasters, among others. We compose the space and save the time for others to move and fill with meaning. The team is careful not to separate art-making from more conventional research practices, and our programming brims with folks who would otherwise never be in dialogue.

At our 2019 gathering, for example, we had Browne share her latest research with Miller alongside choreographer Raja Feather Kelly, as well as a live-recorded theater and performance studies podcast On TAP, featuring guests from a skunkworks engineering lab at Oculus and producers from the Sundance Film Festival. CRCI works across traditional hierarchies of knowledge, the result of years of iterative organizing and community building, to permit simultaneous consideration of performance, technology, and power. While there have been tangible outcomes—companies started up, artistic ventures launched, IP created—such deliverables are less the point of the venture than the process which catalyzed them. It is the process that we ultimately care for the most. Most simply, my hope for CRCI is that with our powers combined, with all of our divergence and disagreement, this odd gaggle might eventually result in the sorts of art, theory, criticism, and practice that define the insurgence required to bring about a less fearful world.

Image of

Choreographer Kate Ladenheim by Keira Heu-Jwyn Chang

Image of

Choreographer Kate Ladenheim by Keira Heu-Jwyn ChangThese days, I teach choreographics at Brown University. I write, speak, and consult on the braid between bodies and surveillant technologies, frequently with the aim of co-creating artistic research practices that fight for more equitable futures. CRCI is a programmatic articulation of these labors, functioning both as a chosen professional family and emerging field. I admit that the thing started with the narcissistic centering of my own weirdass research questions, though this is thankfully no longer the case. Already a generational shift is underway, and my role is increasingly to resource a rising class of dance-interested artists and engineers.

Michaud — my former mentee, now programming partner — recently hired her own former intern, Kate Gow, to help administer the effort. Gow is a self-described “kinaestheticist” and Boston Conservatory at Berklee graduate with a self-designed degree in dance and technology — an orientation in part inspired by attending CRCI. Gow and Michaud will take over much of the management of the 2020 CRCI convening, as well as half a dozen other CRCI-produced gatherings in the works around the country over the next few years.

The traction of these gaggles validates the capacity of artists — dancers, specifically — to articulate and combat bias in body-centric technologies. For centuries, the Western dance tradition has largely been about aestheticized systems of exclusion. If we consider the proscenium stage an early, body-centric technology of surveillance, the fact of contemporary surveillant technologies’ reinforcing bias is no surprise. CRCI attempts to imagine otherwise, and anyone wanting to dismantle the prior art of structural racism should consider themselves absolutely welcome.

CRCI sticky

note aftermath by Keira Heu-Jwyn Chang

CRCI sticky

note aftermath by Keira Heu-Jwyn ChangImmerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.