One day, as I was filing some paperwork, I came across my medical records where it had been written: “Birth Control: Copper T Intrauterine Device (IUD).”

How could I be so ignorant about this piece of technology that’s inside my very own snatch? My self-disappointment then turned to wonder. Where does the copper in my snatch come from?

So begins a SNATCHural HISTORY of COPPER, a transmedia project in which I explore copper, a mineral on which our households, cities, digital desires, and selves depend.

To learn what’s at stake, I trace a line between my snatch and your screen.

The Source

Copper is a mineral requiring an intensive extractive process that has polluted 40% of America’s headwaters. Copper, a mineral, dear reader, on which our on-screen intimacy in this very article depends.

Since we started using copper back in 8700 BCE, we’ve used up all of the best and purest copper that’s been laying around on the crust of the earth. Today, we have to dig deeper through more and more impure rock (ore) to yield the same amount. It’s energy-intensive and highly toxic: while the extraction of gold, copper, iron, and bauxite contributes to 2% of all global carbon emissions, the downstream processing of these metals contributes to nearly a quarter of all global carbon emissions.

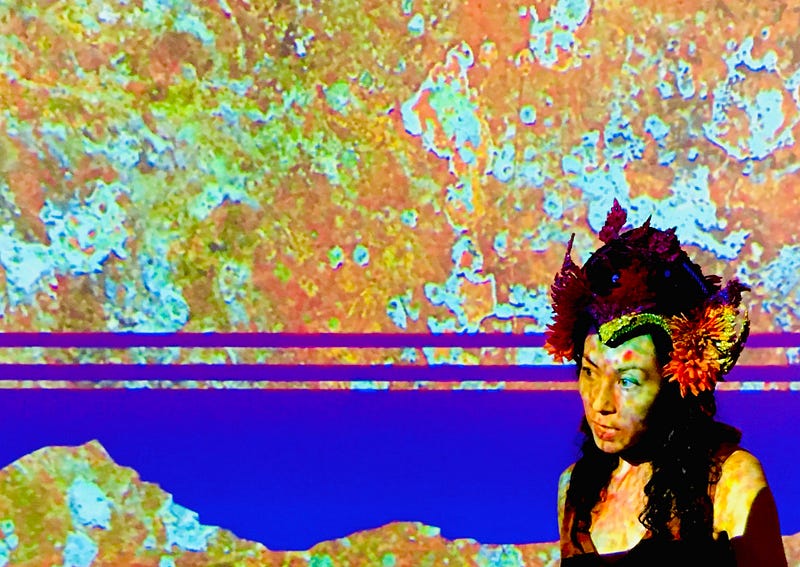

Copperscape 2 by Marisa Morán Jahn, 2019.

Copperscape 2 by Marisa Morán Jahn, 2019.If you are one of the 170 million women out there with IUDs, you may be wondering if the copper in your cooch is contributing to climate change. Good news! Your IUD is effective, relatively low-cost, and a critical low-carbon tool. Just a single penny would yield enough copper to produce ten IUDs.

Likely, the copper in your IUD comes from the Rio Tinto-owned Bingham Copper Mine, which produces 1% of the world’s copper and 70% of America’s copper. The amount of excavated rock (ore) it takes to yield the copper used in my IUD is a scoop of earth the size of a tablespoon. And the amount of ore it would take to yield the copper for us ladies who comprise the global club of copper IUD owners is about the size of a minivan—an efficient and good use of copper.

“Gifts of

Earth and Extimacy” (2020), an installation at 21c Durham by Marisa Morán Jahn and architect

Rafi Segal, invites the viewer to examine three artifacts that extend our digital, corporeal and

libidinal selves: a contemporary copper-based IUD (intrauterine device), an ancient Hellenic

copper-based contraceptive device (“pessary”) from 400 BCE, and a motherboard used in personal

computers. Together, the three artifacts present a fascinating story of extimacy — the mediation

of intimacy through technology — and the continuum between flesh and earth. Altogether these

three gifts sensitize us to desire — and its regulation — as a way of knowing ourselves, each

other, and our environs.

“Gifts of

Earth and Extimacy” (2020), an installation at 21c Durham by Marisa Morán Jahn and architect

Rafi Segal, invites the viewer to examine three artifacts that extend our digital, corporeal and

libidinal selves: a contemporary copper-based IUD (intrauterine device), an ancient Hellenic

copper-based contraceptive device (“pessary”) from 400 BCE, and a motherboard used in personal

computers. Together, the three artifacts present a fascinating story of extimacy — the mediation

of intimacy through technology — and the continuum between flesh and earth. Altogether these

three gifts sensitize us to desire — and its regulation — as a way of knowing ourselves, each

other, and our environs.What are inefficient uses of copper? The greatest source of copper consumption is urban expansion — all those pipes, cables, wires, and AIs running on data farms that power our so-called “smart cities.” As Nicole Starosielski points out, although we imagine cloud-borne satellites to connect continents, today, 99% of all signal traffic occurs through terrestrial underwater sea cables whose inner fiber optic cables are insulated by surrounding copper wires. And the demand for copper is only rising: according to predictions, the demand for copper will increase between 275% and 350% by 2050.

So whether via snatch or screen, most of us living in the global North are implicated in the consequences of copper extraction.

Mine(s) and Others

The majority of those reading this article live far removed from sites of extraction. As a consequence, and in spite of our digital hyper-connectivity, we remain unaware, uninformed, and unable to monitor those powers (corporate, governmental, paramilitary) that profit from mining.

As an artist who’s spent several years teaching art, transmedia, and cultural studies at Columbia University, The New School, and lastly at MIT — the latter institution whose founding was based in part on prospecting for raw resources like copper — it seems imperative for me to recognize and question our role in the extractive industry.

Poster

design by Marisa Morán Jahn for the interdisciplinary workshop she co-taught with Rafi Segal in

2019, supported by the MIT Transmedia

Storytelling Initiative.

Poster

design by Marisa Morán Jahn for the interdisciplinary workshop she co-taught with Rafi Segal in

2019, supported by the MIT Transmedia

Storytelling Initiative.In “Mine(s) and Others,” a workshop co-taught with architect and MIT Associate Professor Rafi Segal, we explored transmedia storytelling’s power to strengthen a sense of connection, strengthen accountability, and call attention to the complexity of extractive landscapes — our dependency and desires, the promise of sustainability, indigenous sovereignty, and a biopolitical revaluation of the subjugation inherent in rapacious extraction. Working in partnership with the Center for Biological Diversity, whose advocacy halted a copper mine from destroying an ecological hotspot where jaguars freely roam, our students sought to create short films that environmental activists and advocates could screen, use in community meetings, and include in social media campaigns to reach broader audiences.

In one video, two students, Caroline Nockelby-White and Catherine Lie, a phantasmagoric cellphone chides its former owner who intended to recycle the phone. The phone instead ends up being disassembled in a junk pile. The backstory here is that due to a host of factors — weak environmental regulation, supply chain opacity, outdated mining laws, and a capitalist free market — extraction is incentivized over recycling (despite the fact that copper is nearly 100% recyclable).

Extracting resources, extracting narratives

Alongside examining these materialist mechanisms, our workshop examined the phenomenological pre-conditions to an extractive approach. As Macarena Gómez-Barris writes in The Extractive Zone (2017):

Before the colonial project could prosper, it had to render territories and people extractible, and it did so through a matrix of symbolic, physical, and representational violence. Therefore, the extractive view sees territories as commodities, rendering land as for the taking, while also devalorizing the hidden worlds that form the nexus of human and nonhuman multiplicity. This viewpoint, similar to the colonial gaze, facilitates the re-organization of territories, populations, and plant and animal life into extractible data and natural resources for material and immaterial accumulation.

Gómez-Barris point out that for extraction to take place, earth and bodies must be necessarily recognized as usable assets that could be converted to personal gain.

As a storyteller, it’s hard not to draw analogies between extractive mining and extractive storytelling: both profit from the lived experiences and environments of historically under-served communities.

Over the past decade, I’ve codesigned transmedia projects with women, immigrants, youth, and low-wage workers (specifically, domestic workers, street vendors, migrant workers) precisely because these stories are systematically excluded. Without these authentic, nuanced voices, democracy is threatened.

Marisa

Morán Jahn interviews her collaborator June Barrett, a Miami-based caregiver and member of the

National Domestic Workers Alliance. Photo by Marc Shavitz, 2017.

Marisa

Morán Jahn interviews her collaborator June Barrett, a Miami-based caregiver and member of the

National Domestic Workers Alliance. Photo by Marc Shavitz, 2017.Situated storytelling, as opposed to extractive storytelling, relates to what Sarah Pink would describe as sensory ethnography: “a route to understanding other people’s emplacement through collaborative and reflexive exploration.” For me, I draw upon my experience as the daughter of Chinese and Ecuadorian immigrants to transform vignettes of grit and grace into larger structural patterns that enable us to act.

Situated storytelling is also cosmological world-building. I turn to and find inspiration from Arturo Escobar’s notion of redes: “In contrast to the English word ‘networks’, the Spanish word redes (nets) suggests a lack of strict pattern regularity. Redes are shaped by use and user and are always being repaired, as life and movements are ineluctably produced in and through relations in a dynamic fashion.” Upturning anthropocentric narratives, Escobar’s notion of redes refers to not only humans but other life forms (animals, minerals, vegetables, dirt) on which we depend.

Situated storytelling as transformation and communion

In a performance-lecture at Creative Time Summit X (2019), I transformed onstage into Aphrodite, goddess of love and copper.

I cajole the audience as a lover and threat. “You need me; I’m already in your blood and perhaps your snatch; I regulate your digital desires and networked selves.”

Skulls swirling in the background, I warn against destroying our tender relationship: “You depend on me.”

I turn to butter again when you confirm you see me, and see us, a continuum between flesh and earth.

On the one hand, situated storytelling is a process of self-transformation in which the nuances of our experiences alchemically conjoin with the myths enriching our cultural imagination. I draw on Giorgio Agamben’s writing in Homo Sacer (1998) to inform my artwork that queries extraction, metallurgy, and transmedia storytelling: “The transformation of metals occurs hand in hand with the transformation of the subject…the care of the self necessarily passes through a work; it inextricably implies an alchemy”

But here, the emphasis on the individuated self implied by the word “self-transformation” denies the power of stories to transform ourselves relationally, as entire communities. Situated storytelling, I’m suggesting, is a process of relational transformation, a ritual or communion whose participants together undergo a shift in being.

An artist of Chinese and Ecuadorian descent, Marisa Morán Jahn’s work has engaged millions through worker centers, museums such as The Museum of Modern Art and Brooklyn Museum; media such as PBS/ITVS, The New York Times, Artforum, CNN, BBC, and Univision; civic bodies such as The United Nations and Obama’s White House. An educator at MIT and The New School, Jahn has received awards from Creative Capital, Tribeca, Sundance and is the founder of Studio REV-.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.