i-Docs research fellow Julia Scott-Stevenson gives a rundown of her visit to the Alternate Realities showcase at Sheffield Doc/Fest, with additional comments from Mandy Rose and Juliet Lennox.

I’m handed a VR headset which feels disconcertingly wet when I place it against my face. At first I think perhaps the attendant has been slightly overzealous with cleaning it between users, but soon enough I realise why it’s damp when my own tears start pooling on the foam padding beneath my eyes.

Vestige

VestigeVestige is a fifteen-minute experience, exploring the grief of Lisa after the death of her husband, Erik. Animated fragments of memories surround me, and I can walk towards or away from them, triggering new ones. I shuffle tentatively, as my headset is tethered above me to the top of the dome I’m standing in; occasionally I brush up against the triangular pieces of set decoration around the edges of the dome.

The Alternate Realities exhibition at Sheffield DocFest (7–12 June) contained an impressive array of immersive work, showcasing a range of the tools and tech currently available. A popular theme emerges among many of the projects traversing emotion, grief, the mind, and relationships with our fellow humans. In Vestige, an actor playing Lisa provides a voiceover monologue as she digs through her memories of her time with Erik. As her voice breaks, the effect is heart-rending, yet I’m not sure what the intention is beyond this. I have nowhere to direct my emotions, other than to walk away considering the terrible sadness of the moment. Perhaps that’s enough.

After a few projects in a row with similar weighty themes, I needed to talk through the experiences with colleagues. Following is a discussion with Mandy Rose and Juliet Lennox of the Digital Cultures Research Centre about the various projects we saw.

Mandy — The one I liked most was Porton Down, because it actually used the VR experience to question the use or ethics of VR. It tells the true story of a man who was subjected to military trials involving mind-altering experiments in the 1950s. What you get in the experience is animations which tell that story. These are intercut with scenes when you find yourself in a lab, and are directed to take a series of tests of your cognitive abilities. It’s disconcerting. Once or twice the lab assistant tells you results that you don’t think are right, but you have no way to protest. At one point when you are trying to do a test the visual environment gets very distorted so that it’s impossible to follow instructions. When you leave you get a print-out that suggests that you have been assessed in ways that you weren’t aware of, too. I think that was a kind of fiction, but it was good. It called attention to the ways that a headset-based experience can be used to track the user. In other cases, though, I began to wonder why we’re seeing so many projects which visualise disturbed or distressed states of mind. Manic VR did it well in many ways. But I wish we could get past this preoccupation with walking in the shoes of another, seeing through the eyes of another…

Julia — Yes, I did feel quite drained at the end of a long day of stories of distress, sadness and loss, across the 360 degree works too. Vestige made me really cry, and the animation was beautiful, but at the end, I was left wondering whether the monologue could have been delivered in some other way. I did enjoy Manic VR, particularly the elements that I assume were meant to represent the “up” stage of bipolar — floating through space with supernovas and manipulating streams of light with my hands. I also thought it was a useful trick to have the hand controllers vibrate when you’re supposed to reach for or touch something.

Manic VR

Manic VRJuliet — My hands were the wrong way around in that part of Manic VR [Julia — mine too!], so I took the controllers off and switched them over midway through. I think it kind of demonstrates that none of the pieces were “quite right.” The attendants and set up are so important . If you’re rushed through, or it’s too noisy around you, or the headset doesn’t sit well, that all impacts on the experience. It seems we’re still at a stage where there’s lots more to get right.

Julia — My favourite was perhaps Is Anna OK? (A VR piece which tells the story of the relationship between twin sisters, after one of them experiences a serious brain injury. Two users experience the work at the same time, each one from the perspective of a different sister). I was Anna (the twin with the brain injury), and I really appreciated that I was encouraged to speak to the other user (who saw the story as Lauren) afterwards. We discussed how the experiences had differed, and learnt more about how the other sister saw and felt things.

Mandy — Yes I liked the agency in Is Anna OK?, being able to pick things up and interact. I enjoyed being able to throw objects around and have a tantrum at one point. The set design was also well thought out, with the real picnic bench and street lamp a neat device for staging.

Juliet — I think it’s interesting that so many of the VR pieces added objects that tethered them back to the outside world in some way. Is Anna OK? gave you a letter to read, Terminal 3 gave you a badge to wear, Face to Face took a photograph of us while we were in the experience and gave it to us afterwards. Is this perhaps some indication that creators are realising we need something more than the virtual experience?

Is Anna OK?

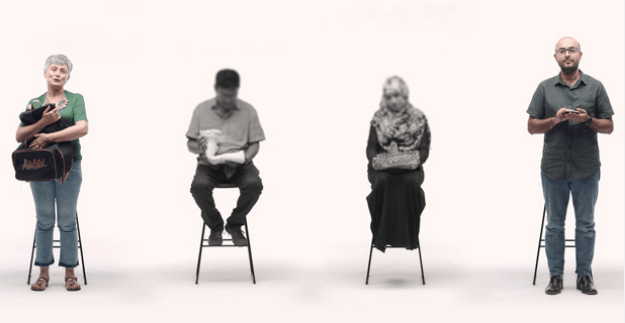

Is Anna OK?I really liked Terminal 3 (an AR work in which the user plays the role of a US immigration control guard and has to interrogate an AR representation of a real person attempting to enter the US). I liked how the character became slowly visually clearer through the piece, the more questions I asked.

Julia — I also liked Terminal 3, and experienced it in multiple layers. On the one hand, I would occasionally remember I was supposed to be a border guard and wonder if I should be asking tougher questions. But I was also just interested in the woman and her story. In a way, I always knew I was going to let her into the US at the end.

Mandy — I thought Terminal 3 was pretty good too. The lighter HoloLens headset was such a relief after being closed in by the VR HMDs. And the ideas it explored were interesting. I found I was quite keen to role play being the guard (which of course made me a little uneasy — shades of the Milgram experiments). But I thought the directing was a little off, because the interviewee didn’t talk as if she was answering questions from a border guard. It seemed like she was chatting to a friend.

Julia — Yes, that did somewhat reduce the jeopardy of the experience. But it was impressive. I had to ask one of the volunteer attendants afterwards if anyone ever says no to allowing the character into the US at the end. She replied that she’d experienced the work a couple of times and so had tried different paths, including denying entry at the end. Ultimately, it seems to be about how that sits with you, the guilt of it.

Juliet — I think the exhibition space really benefited from the placement of Belongings on the wall at the end (an interactive wall-sized projection of six refugees. Pointing a smartphone at a character triggers the person to rise and tell a story about a belonging of theirs that they brought with them from their home country, and the audio plays through the phone speakers or headphones). I thought it was a really simple and effective interface, and a welcome alternative to engaging through a headset.

Belongings

BelongingsMandy — The problem though was with choosing someone from the line-up. It felt a bit like “displaced persons-on-demand,” the logic of getting to activate the characters, taking over their agency in a sense. But you are right that being able to use your own phone as a navigational device was very cool and effective. It would be interesting to see that used in other ways too.

Julia — I thought The Day the World Changed (a VR experience about the bombing of Hiroshima and nuclear disarmament) was overall a missed opportunity, and a great example of trying to do too much, both in terms of tools and experience. There were so many different elements that didn’t hang together very well: a lot of mismatched visual content, the interaction with some items that triggered audio was a bit clunky, and the blue dots coming out of our hands at the end were quite confusing as to what they were for and how much control we had over them. From an installation perspective, with four users at once our cables kept getting tangled and a volunteer at one point grabbed my foot to lift it over a cable. The animation of nuclear mushroom clouds appearing across the globe was quite effective, as was the moment of realising a thousand missiles were pointed at me, but in general there just wasn’t a coherent story to the piece.

Mandy — To my surprise I found some of the 360 video experiences the most effective. Danfung Dennis had two pieces about climate change in the programme. I saw one, Feast, which was about the destruction of the rainforest to make way for cattle ranching. There was something very powerful about using the 360 camera to document this process. In part it had to do with how they took the camera right into the middle of things. I also very much liked Sanctuaries of Silence, which was another piece with a message, this time about how places untouched by human and machine sounds are becoming extinct. It centered on Gordon Hempton, a “sound ecologist.” The piece really made you listen, and gave you a very welcome experience of calm, which was rare among the pieces on show.

Life After Hate: Meeting a

Monster

Life After Hate: Meeting a

MonsterSome final thoughts

I finished the day with a visit to the Alternate Realities Portal, a dome in which six or so people could sit and view 360 degree video on the walls around them. Perhaps ironically, it was the piece Life After Hate: Meeting a Monster which provided a note of hope on which to end my Sheffield exploration. It presents the story of Angela King in reenactment, with Angela herself narrating. An angry and lost young teenager, she found acceptance among a group of white supremacists, and began a predictable journey towards rage, violence, and imprisonment. The translation from a VR headset to the igloo walls was not without quirks; some compression of the height of the image made bodies occasionally stumpy as if in a funfair mirror, and the image was not always clear.

However, I imagine it would be an effective story in a headset. When Angela reaches prison, she sits nervously among a number of black women, and is surprised when they calmly approach and engage with her. Her views are progressively challenged, and she emerges with a clear understanding of the error of her ways. She co-founds Life After Hate, an organisation dedicated to helping people leave white supremacy groups.

While a work about life after white supremacy may not exactly be uplifting, the demonstration that something as simple as conversations and interaction between people who are different can lead to change is encouraging. In many ways, this story is classic documentary fare — a personal journey through adversity, and connections with a broader political and social story. Perhaps the traditional approach to narrative, combined with some of the affordances of VR, is what leads to both stronger and richer work. Of the pieces I saw at the Alternate Realities showcase, Is Anna OK? and Terminal 3 came the closest to achieving this interplay.

This post was originally published on the i-Docs site

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and is fiscally sponsored by IFP. Learn more about our vision for the project here.