How should digital producers navigate privacy?

Between eavesdropping bots, the Equifax hack, and Russians targeting Facebook users in battleground states, issues of digital privacy and surveillance are now leading headlines daily. How are interactive producers and artists addressing these topics in their work — and how much is too much when it comes to collecting audience data? To find out, Immerse sat down with media producer and Mozilla’s Commissioning Editor Brett Gaylor and creative director and Visiting Researcher at MIT Open Doc Lab, Sandra Rodriguez.

Both of you worked on Do Not Track — a groundbreaking personalized documentary series about online privacy that launched in 2015. What’s happening in the long tail of that project, and how is it influencing the work you’re doing next?

Brett

Gaylor

Brett

GaylorBrett: It’s still being exhibited — we had a lovely invitation for the Biennale of Santiago, Chile, where it will exhibit this fall. We’re also in conversation with the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), Arte, and Upian, our producers in Paris, about archiving the project.

I know from all the email from creeped-out users that it’s still regularly visited. They also let us know when things break: If one of the APIs that keep it all together stops working, you’ll know that day!

In terms of how it’s influencing current work, for me it reaffirmed that online privacy and security is something we need to keep helping audiences understand. My current role at Mozilla is as a commissioning editor, and this year we partnered with the Open Society Foundation on a program called Surveillance Counter Narratives — helping media producers create work that disrupts the typical discourse around privacy, which tends to focus on a false binary between the privacy of individuals and the desire of state actors to monitor communications to disrupt terrorists. We have an open call for proposals that Immerse readers would be welcome to apply to.

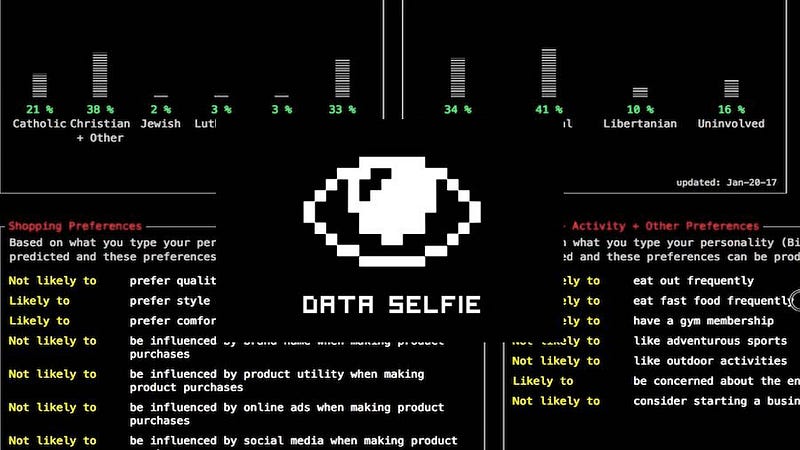

One example of this work is Data Selfie, a plugin that allows you to see yourself as Facebook does. It uses some of the same techniques we employed in Do Not Track but has a more sophisticated product-like approach. We’re supporting Hang Do Thi Duc as a fellow to create more work like this, work that helps people understand the data collected about them.

Another is a virtual reality work called Porton Down by MIT Open Doc Lab fellow Callum Cooper. He’ll be prototyping an early version of this work at the Mozilla Festival this week.

The second answer for me in terms of how Do Not Track influenced my future work is that it set up my current project exploring the Internet of Things. My first feature, Rip!, was really optimistic about the Internet and the role it would have on our society. Do Not Track was created during a period where I started to feel some apprehension about the business models of the Internet, and how these lead to far too much personal information about us being shared online.

My next project is going to use our current infatuation with connecting everything in the world to the Internet as an opportunity to say: Hold on. On balance, is the Internet actually playing a positive role in our society right now? There’s plenty of evidence to suggest it isn’t, but also a need to re-discover the parts of the Internet that we like and nurture those elements.

Sandra

Rodriguez

Sandra

RodriguezSandra: Well, well. That tail is long…

So, I have two hats: I’m a maker (documentary films, webdocs, immersive and interactive media) and also a sociologist of new media technology.

When I started working on Do Not Track, I had just finished a PhD that focused on how young adults used and made sense of online sharing practices when striving for social change. I conducted in-depth interviews with 137 young Canadians aged 20–35 years old and was trying to underline the whys and hows of their everyday social media use. And the findings were unexpected.

Rather than cynical, apathetic or disengaged technophiles, these young adults were part of a social culture deeply marked by networking, by a remix culture and social mobility. On one hand, many did not feel that sharing or forwarding online defined political change or action — too easy. But they strongly believed that sharing online was an important part of “spreading the word” — forwarding and sharing everyday experiences through social media was a way of being heard, voicing others concerns, or influencing and shifting collective ways of thinking, acting and perceiving. That was the conclusion of my PhD dissertation — sounded good and meant a lot.

In other words, we love sharing (yay)! But data tracking and data-driven decisions cast a real shadow on this utopian power of retweets. Do Not Track tackled this subject front-on.

The objective was to open a public conversation on how tracking affects what we feel is normal in this new social contract. Everything we do — from taking an Uber, to buying online, to looking for home renovation pictures — is tracked. It forms part of an economy that’s ever-expanding, and that loves categorizing us into little boxes.

I don’t really like boxes. Nor do I think I fit easily into one; interest proposals and Google suggestions are always off for me. But Do Not Track did more than just point fingers. We had fun, as makers and creators, we had fun tracking trackers and tracking users. It was very meta.

And the more we dug into this, the more I started discovering many cool toys, apps and software out there that could help creators like ourselves track audiences, users and visitors. It was exciting. It still is. Imagine all the cool things you could tell a user about the way he/she/they behave, react, or respond to an experience. That’s all super-positive. But it’s also scary sometimes and, just like consumer tracking, it raises many important ethical questions. And that troubled me — especially when tracking bleeds into the world of art, expression and creation.

So after Do Not Track. I started working on a research-creation post-doc project (supported by SSHRC and Lab Culturel and incubated at the MIT Open Doc Lab) entitled Hello_Publics. The idea was to question how creators use tools to track their own publics and then play on that to create an interactive installation that tracks its own public, loves it, mimics it — a bit like Jane Goodall reproducing apes’ behaviours to better understand them. For many makers, creators and funders, new tools mean new amazing and easy ways to understand what a user or visitor likes, feels, how they interact with the content. This is useful. It helps create better, more functional, even sometimes more personalized and alluring experiences. But it also raises questions about how we perceive the “public” — are they only reactors? Consumers and likers?

Tracking questions also really apply to emerging tools like AR and VR. I am working as creative director and producer of immersive VR projects. Here, too, tracking users, evaluating user behaviour, is a huge thing. Brett… I think we’re cursed — we love the new tools with which we get to create new things. But are we doomed to track?

So, both of you tell this story about moving from early enthusiasm about the liberating potential of digital technology to a much more wary and qualified stance. What are you doing in your own lives to protect your online privacy? Are there tools or resources you think makers need to be using?

Brett: I do practice some measure of “digital hygiene” — for instance, I use two-factor authentication for services like Gmail, Twitter, or basically anywhere it’s offered. I also use a password generator so that every website or service I log in to has a unique password. That way, if one service gets hacked, it doesn’t give an attacker access to everything else in my life. It’s also handy in that I don’t have to remember everything myself when I log in.

In general, working on Do Not Track made me much more skeptical and choosy about what information I share and caused me to consider my “threat model.” A threat model is a process to analyze how a potential adversary could compromise your personal information, and what kind of harm they could cause in doing so.

I think if creators are working with sensitive information, their threats are more severe — so they should absolutely be taking steps to make sure their communications are encrypted and that their operational security is tight. I think this is even more important if they are trusted with information about people in vulnerable communities, who are more likely to be subjects of surveillance. If you’re working in a country where the state is known to surveil citizens, make sure that you aren’t putting someone at risk by communicating with them or holding information that a state actor could use against them.

Sandra: Yes. I agree. That also goes for they ways in which we can use tools to create experiences. I have to say aside from what Do Not Track marked in terms of my own “digital hygiene,” I haven’t changed all necessary habits. Yes, I do still have a Do Not Track sticker on my computer cam… it kind of reminds me I should do more. But I believe the important word here is “know.” Have a constant thought or at least an acknowledgement that whatever keeps being promised to users and consumers about the way their data is being used or who gets to see what is mostly unprotected by any kind of regulation. And, most importantly, it happens behind closed doors. So for me, it’s more about understanding the powers at play — reminding myself and others of important questions related to data tracking: who owns the data? What data are they using, to what purpose? What protection do we have against the way this data could or is actually being used?

This also applies to creation. In the years since Do Not Track, it’s been exciting to see the number of projects that track users’ data — even biometric data — to enhance the experience, see biases in users’ behaviours, etc. And it’s inspiring but… I also worry. In my own life, to answer the question, I got both excited and frightened with the new iPhones. Facial recognition can be used in super-playful ways, sure. But having that to unlock a phone taps into so many biases and discrimination issues. On this particular double-edged sword I really like the work of creative coder researcher Joy Buolamwini, at the MIT Civic Media Lab. She leads the Algorithmic Justice League to fight bias in machine learning, and has been recently speaking about one of many projects she’s developing. For one project, she wore a mask for several days, trying to see all the systems that would fail or work better while changing her skin color. Pretty revealing!

If tracking your audience members is getting too creepy and invasive, what are some other ways that media makers and funders can think about the impact of their projects beyond reach and social engagement numbers?

Sandra: Well, again, it’s about knowing. Brett, I think you put it best when you were defining Do Not Track’s main objective: To make sure we have a public conversation about these issues — and that means making sure said “public” understands enough to not feel completely excluded.

Part of the approach of Do Not Track was to track users and track trackers, all while showing users their own data and giving them power over whether we could use it or not.

For the “Big Data” episode I directed, I wanted to make sure there were two layers of tracking made transparent to users. The first was the obvious “choose an option that represents you” but also tapping into the visual culture of all the quizzes and tests we fill in for fun and that are, well, in many cases, just ways of compiling and refining data to create a digital portrait of sorts.

For some users, that was already learning something new — that these innocent tests and daily selections of options are not so innocent after all. But the second layer of tracking was more insidious. We also decided to track behaviors: Were you diligently watching all the clips? Were you skipping them? Were you frantically clicking or moving your mouse? Were you distracted by all forms of aesthetic interactions that were added to the visuals? All this tracking, too, had to be made transparent.

That was the “Aha-moment” part of the experience — making sure users first understood that they were being tracked, and even when they did, making sure they realized there’s always something else that is not fully transparent and that can be used for many forms of categorization, some good, some very discriminatory.

So for makers, why not use these tools to show what’s happening behind closed doors? I think tracking doesn’t necessarily measure impact. In fact, impact is not always measurable. Neither is social engagement. It’s always been the role of the artist to ask questions, to disrupt, to invite reflection and deeper thoughts. With the work I am now doing on artificial intelligence and machine learning, I want to open more Pandora’s boxes. Why not?

An artist from Bucharest told me a fantastic quote from Buckminster Fuller, while trying to explain what she likes in my projects: “We are called to be architects of the future, not its victims.”

I’m also just thinking of another bug I have with measures used to evaluate the “impact” of interactive and immersive projects and experiences. In sociology, there are questionnaires and surveys, of course. But there are also other approaches where we ask polled individuals to give feedback on the questions themselves. Questions can be biased, or poorly formulated. With digital tracking, and biometrics, gaze-tracking, etc., it’s even more difficult to say: “Well, you see, my headset was glitchy here and so I was not looking away from a character, I was trying to fix the head tracking.” Or, “I got a hair in my VR headset and kept trying to move it by blinking my eyelashes” (true story). Or any other weird behaviours we may have that might not be interpreted correctly by the tracking tools we used. It’s hard to tell a computer “Sorry, hair in my eye. Can we start again?” like you would an interviewer.

Brett: For me a lot of this comes down to agency and transparency. Do people understand the bargain you are making for their data? With Do Not Track we tried to be really upfront about that, with the central value proposition being, “If you share data with us, we’ll tell you what the web knows about you.” We asked users to create an account with us so their activity could be stored with a profile.

If you do that when you watch the series, you can see what data is collected, when it was collected, how you connected, and the bespoke information that’s collected in each episode. This is placed in an API that each episode could have access to, so that data collected in one episode could be relevant in another. We also let people delete their accounts on this page, or specific pieces of data.

With this bargain, we found that a lot of people did actually sign up to receive future information and future episodes — about 50,000 people had signed up for this last year when we did a case study with Media Impact Funders. At that time, that was about a 5.6 percent “conversion rate” from casual viewer to committed “member.” I’m not sure what the numbers are now — we’ve had more unique visitors since then and I don’t know how many people have signed up for the newsletter — presumably fewer since it’s no longer being released serially every two weeks.

I think that you can get a sense of the engagement rates of your work without tracking people in a creepy way. At Mozilla, we partnered with the Harmony Institute to develop something called a “Total Engagement Index.” This was a way for us to set a benchmark of how audiences were reacting to content on our social channels, and then we set internal goals to improve this. Basically what we do is weigh audiences’ reactions to a piece of content. If they just watch it, we might give it a score of one. If they “like” it, we might give it a score of 2. If they share it, we’d give it a 3, and if they take an action, we’d give it a 5. This way you optimize what you’re making for shareable and actionable content. And you don’t need to know what books people read or their ethnicity to do this kind of analysis.

So, now we’ve got wearables tracking our bodily functions, online platforms tracking our consumer preferences, and Roombas tracking and sharing the contours of our houses. What do you think the next frontier in tracking will be?

Sandra: I’m reading this and the next thing I think of is a fully dystopian future. I mean… I love serendipity. I love coincidences. I love discovering something I didn’t know I would like.

All of this tracking is usually associated with promises — you’ll know what you drank and if you should drink more. (What about just feeling thirsty?) Or we’ll offer you things you may like. (Well, offer me things I might not like for a change.) I personally don’t want a company to have my bodily functions, preferences and house contours! Because my experience tells me about 50 percent of the time, they get me wrong. That’s like asking your doctor to flip a coin to decide if you’re sick or not. I would say no to this doctor. Why are we saying yes to these companies and services?

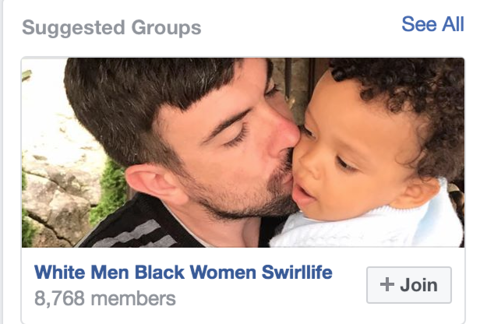

Yesterday, Facebook suggested groups that might interest me. For three days in a row now, it suggests “White men black women swirllife.” I went to look at the group. It’s a group of lovely families sharing their own life experience of being a mixed race couple. I don’t know what to make of that (not the couples, obviously — Facebook). Is Facebook trying to tell me I should be in a mixed-race relationship? That I am? Or is it assuming I am?

Basically, I don’t mind the suggestion. But the question is: Why this one? Is it based on my last name? Oh, and no, I do not want a T-shirt or sweat-shirt that has my name, occupation, or favorite sport on it. How simplistic do these algorithms think we are?

So what’s the next frontier in tracking? I’m afraid to say. I feel new developments try to track everything, yet can’t figure us out correctly. What if I say dreams are the next frontier — will someone try to develop trackers that do that, too? I surely hope not. I have very strange and imaginative dreams and I love them just like that.

Brett: I definitely think the next frontier of tracking is our home. I’ve been doing some research for a project about the Internet of Things, and watching a lot of goofy “home of the future” promo videos from Silicon Valley. Almost all of these videos feature someone turning lights on by waving their hands, or issuing voice commands that make coffee or check the weather. What’s clear, then, is that in the home of the future being dreamed up in Silicon Valley, you’re always on mic and you’re always on camera.

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.