An afternoon with Klasien van de Zandschulp and Ali Eslami

This is number 3 in a series of posts that is part of a one-year research track called Our Brave New World, produced in the context of the Creative Economy theme of the Fontys University of Applied Sciences in Eindhoven, and in collaboration with the Amsterdam based design studio ARK. In this track we are building an interactive mapping of the Creative Industries in the Netherlands and look at how the creative industries can be framed as a blueprint for our possible futures and how we can keep track of their findings to give change a kick in the tail.

Outdoor perspective of Sacred Hill

Outdoor perspective of Sacred HillWe take for granted that only certain kinds of things exist — electrons but not angels, passports but not nymphs. This is what we understand as “reality.” But in fact, “reality” varies with each era of the world. It is shaping the field of what is possible to do, think, and imagine. Our contemporary age has embraced a troubling and painful form of reality: Technic.

—Technic and Magic: The Reconstruction of Reality, Federico Campagna

What is Real?

As Campagna shows us, it is technology that sparks our curiosity about an alternative reality: an existence beyond the physical body and space. The rise of virtual, augmented, and digital realities is making the question “What is reality?” all the more urgent.

Sacred Hill is a project that links these shifting notions of “what is real” to an alternate state of mind that offers the opportunity to a feeling of enlightenment or of a supernatural or even superhuman state of being. This quest forms the main motivation of the project Sacred Hill, and inspires the speculative questions this project raises: What makes us human in a virtual world? What do we need to be able to live here? Is it possible to feel enlightened or supernatural in virtual reality?

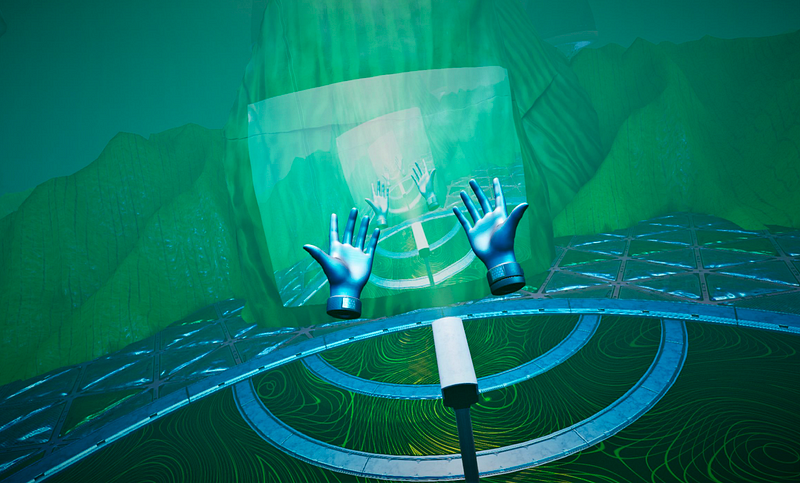

In the

beginning of the experience, your body is still there…

In the

beginning of the experience, your body is still there…The body

For quite some time, our bodies and minds have no longer been considered stand-alones. Even if we prefer to look at cat and dog videos on Instagram, as individuals we are data, nodes on a network, and nostalgic about our mythical pre-technological past.

The soft-spoken woman who once said she wanted to be “rather a cyborg than a goddess,” Donna Haraway, was an important inspiration in this quest to redefine our bodies in this changing world. In her famous essay A Cyborg Manifesto (1985) she proposes to get rid of the boundaries between human and animal, human and machine, and the physical and the non-physical. Through the notion of the cyborg, Haraway aims at new forms of feminism, beyond the limitations of traditional gender and politics, but she also frames the body itself as the battleground for identity.

Your body is an organised pile of muscles and bones, your body is a citizen, your body is a protestor, your body is a place of violent acts, of loving acts, your body is online, measured, analysed, felt, technological, a partly nonhuman body. Why should our bodies end at the skin?

—A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century, Donna Haraway

Inspired by this quote, the Sacred Hill team explored the correlations between space, human body, perception and alternate ways of communication in both the real as the virtual. They explore “spatial learning,” in which they use their bodies and their senses to explore the connection between a virtual, physical, and an “extra-human” experience.

Sacred Hill

in its lab set-up at The New Institute (image Anita Bharos, LAB8WORKS)

Sacred Hill

in its lab set-up at The New Institute (image Anita Bharos, LAB8WORKS)Sacred Hill

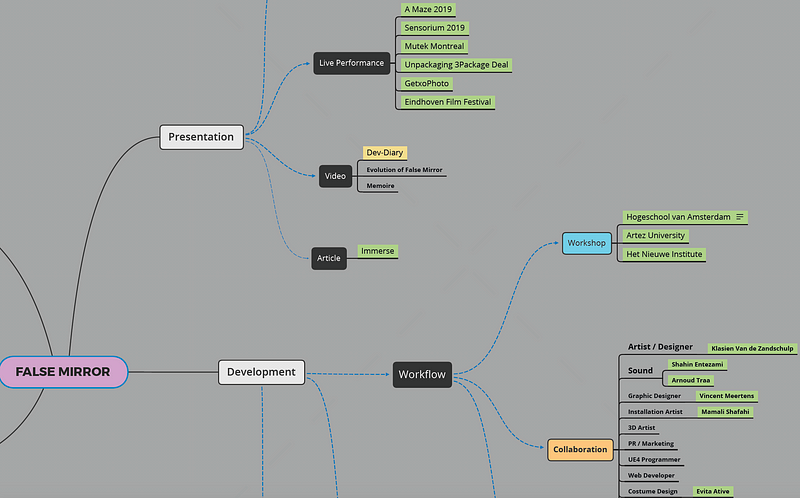

Sacred Hill was one of the highlights of the Interactive program of the Nederlands Film Festival held in September 2019 in Utrecht. The installation is the second step in a longer research project initiated by Ali Eslami, False Mirror. The project is a multi-year investigation in the shape of an endless speculative city under construction, and considers the question: “What would it mean to live in VR?” The multi-project’s preliminary outline encompasses installations, VR experiences, performances, labs, teaching practices, articles and literary research. In collaboration with different artists, in each new “chapter” of this work a new space will be added that explores new questions and perspectives.

Part of the

Sacred Hill development planning and mind map

Part of the

Sacred Hill development planning and mind mapThis second space of False Mirror is called Sacred Hill. It is a ritual machine developed in collaboration with artist and interaction designer Klasien van de Zandschulp and a VR exploration of humankind’s need for spirituality and systems of belief. Jointly they invited Mamali Shafahi as installation artist and many others, such as audio wizards, costume designers and scent composers, to create a fully immersive experience.

Ali Eslami and Klasien van de Zandschulp, as their names give away, come from very different backgrounds — Ali has Iranian Islamic roots while Klasien was raised in the Dutch Christian bible belt. They wondered what would be needed to live in VR for longer periods of time. They discussed the rituals and elements from different forms of occultism, meditation, witchcraft and natural drug experiences and asked how rituals and systems of belief could bring meaning to this world. How can we make the virtual space our own? Can we live there, inhabit it?

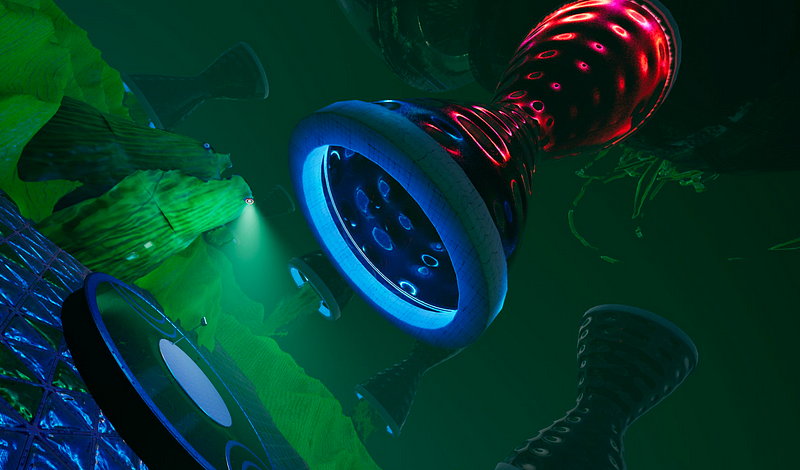

Mounting

platform in Sacred Hill

Mounting

platform in Sacred HillOver the course of a couple of months, during which they tested different versions and appearances of the work together with the audience, eventually they answered these questions through two different strategies: Firstly, they experimented with a new form of architecture, one not based on the laws of gravity and where the body has a different role in both locomotion and the way the environment could be shaped. Secondly, they sought ways to soften the gap between the real and the virtual, the human and the machine, and the digital and the physical. Here the body does not end at skin, and a new shared reality is born.

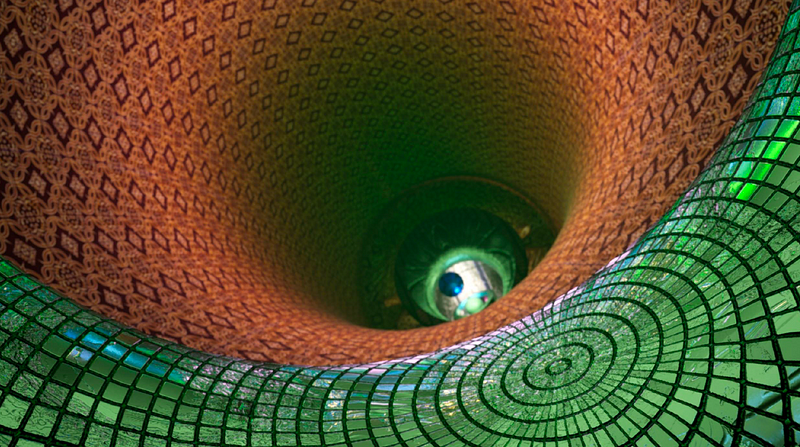

The Ouroburos, an ancient symbol

depicting a serpent or a dragon eating its own tail.

The Ouroburos, an ancient symbol

depicting a serpent or a dragon eating its own tail.Ouroboros

One of the things that puzzled Eslami and van de Zandschulp was why there are so many traditional buildings with walls and ceilings in VR. World building in VR seems to get stuck in similarities with the everyday world of stone, sand, and recognizable landscapes.

Their starting question for Sacred Hill was: What happens if we get rid of these architectural rules and try to look in a totally different way at space? This led to a new kind of design, inspired by the Greek mythical figure of the ouroboros: an ancient symbol depicting a serpent eating its own tail.

As also in Ancient Egyptian culture, the serpent illustrates the formless disorder that surrounds the orderly world and is used for the periodic renewal of the world. And to renew the world is exactly what Eslami and van de Zandschulp want.

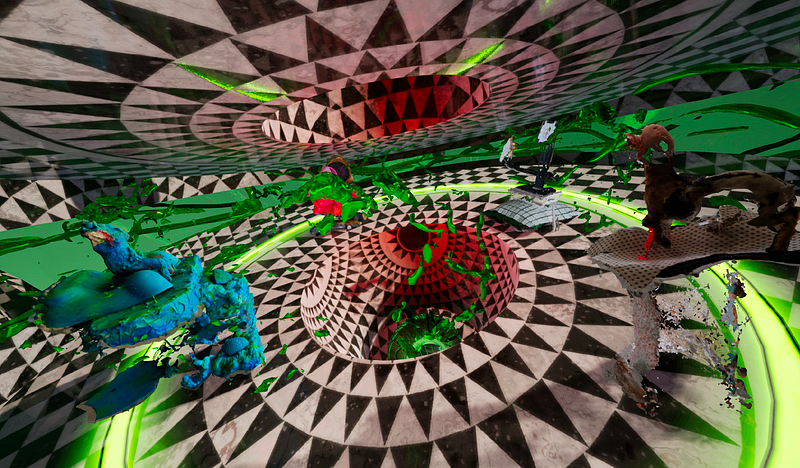

Deep down in

the VR experience of Sacred Hill

Deep down in

the VR experience of Sacred HillBased on this circular form, Sacred Hill consists of a series of four different tunnels inside this ritual machine, through which the visitor moves towards an ultimate understanding: the final “sacred hill.” The tunnel you enter is a torus, a donut like three-dimensional shape, and gives the illusion that you are moving through it, while in fact you are not moving at all; you are static and the whole room is moving through you, transforming you slowly into an increasingly disembodied state of awareness.

As you move through these tunnels, you discover how you can take over this space: you can shrink or enlarge the tunnel with your body, wrapping it around you, or making an impact on the space in different ways.

The

installation view at the Nederlands Film Festival

The

installation view at the Nederlands Film FestivalBetween the virtual and the real

Sacred Hill is a multilayered experience. The first step when you “enter” it is a physical one: You find yourself in a blue-lit environment in which the walls are covered in a fluorescent grid. The design is like a VR space: When you move too close to its borders, a grid appears to warn you that you have reached the edge of the world. Alienating and fluorescent details make you stop, look, and wonder where you are.

The second level in this world is a personal tarot reading but with a twist: a futuristic-looking costumed priestess asks questions like “How do you feel?” and “How would you like to feel?” and draws you a card to prime your mind.

The cards are to help you to arrive at an alternate state of mind and augment your experience in the VR. They cover four general categories that directly relate to the four tunnels in the VR:

- tangibility & touch,

- transformation & time,

- vision & light, and

- perception & perspective.

Each category includes four different cards which determine the story that will guide you through your Sacred Hill ritual. This gives you points of focus and helps you to create meaning in relation to your personal situation, stimulating you to open your mind, and intensifying the experience.

Card

reading ceremony

Card

reading ceremonyEach card connects to a space in VR in which you are introduced to different interactions that exceed the capabilities of your human body. For instance, you might be able to play with time by slowing it down by using a body movement, or change the perception of the space around you.

This part of the process was extensively user-tested. During the preparations and research the team were able to use an exhibition space at the New Institute in Rotterdam, the co-commissioner of this work. The audience members were part of the lab as witnesses or participants and, based on these interactions, iterations were implemented inside the exhibition space and the VR. After the reading, the visitor’s mind was prepared and ready to enter: their headset was put on, and off they went.

Bring on the third stage: Here there are different smaller steps to take which gradually take you further into the digital reality, as you leave your physical body behind. At first you still see glimpses of the real world that surrounds you. You see the installation with the other visitors, and you see yourself standing from a distance, which gives you the first out-of-body experience. There you are, geared up and ready for God knows what. But you are already taking off. You see your hands in VR — not really your hands, but close enough to still feel present in a recognizable world. As you enter the first torus, slowly the images of the real world fade. The tunnels start moving through you, reflections of the real world dwindle. Your hands disappear. You are swallowed by the snake as you leave your physical self.

Trippy

final torus of Sacred Hill

Trippy

final torus of Sacred HillSlowly moving and pulsing from shape to shape, eventually you reach the outer end of the torus and get your reward: the ultimate glimpse of “sacred hill.” Here I provide no image to show you what this is like; you have to find out for yourself.

Fiction or the real?

In an interview for the NFF, journalist Anton Damen asked a very specific question: “In what year will mankind spend more time in virtual reality than reality?” Zandschulp replied that we were already there: “People often say ‘reality’ and ‘virtual reality,’ as if they are mutually exclusive. In doing so, you neglect the fact that virtual reality is also real.”

Eslami also explained that to him False Mirror felt as real as Amsterdam. “I can go there anytime, I know my way, it is part of reality already.” Both artists claim that when we look at everyday life, we are already in a similar state. Commuting on the train, with everybody on their own phone or laptop, more people seem to live in a virtual reality than do not. Jumping back and forth from Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook is flopping in and out of different sorts of realities. As Sherry Turkle wrote in her book Life on the Screen back in the 1990s: “RL [Real Life] is just another window.”

Arguably we could say that Haraway’s cyborgian concept of the boundaries between humans and machines fading is becoming increasingly clear in a more or less unavoidable way, physically, and, in particular, mentally. Do we care? Maybe so, but basically the only thing we can and should do is to pay attention to the effects of the transitions that are taking place, both on us personally and on our society — to the what and how, and why. And while we are at it, just enjoy the ride.

And this is exactly what Sacred Hill does. To Van de Zandschulp and Eslami, the personal experience is key. They merely deliver the building blocks of the story; the rest is up to your imagination, and the meaning that you yourself attribute to the experience.

Ann Demeester, former director of the Amsterdam Arts Center De Appel and current director of the Frans Hals Museum, talks about her interpretation of the relevance of human fiction on the ideas of the German philosopher Hans Vaihinger. She explains how his idea of the act of “pretending” is a necessity in life. It is not only an instrument in film, art and literature, but is also essential for the functioning of the human brain and for human wellbeing: “It is the crux of our thinking and feeling as humans.”

By using speculative design we are able to explore this human power, “human fictions” in a future virtual space to inhabit. By questioning and adjusting our ideas and visions, it is ultimately possible to exert influence on the world that is ahead of us, as Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby state in their book Speculative Everything, quietly echoing the words of Campagna: “If our belief systems and ideas don’t change, then reality won’t change either. It is our hope that speculating through design will allow us to develop alternative social imaginaries that open new perspectives on the challenges facing us.” This is what Sacred Hill is all about.

When Damen asked the artists how often one should experience this ritual, van de Zandschulp replied: “Once a day, minimum!” And this might seem just the right amount of time to experience this speculative human fiction, so we are able to arrive at alternative social imaginaries that open new perspectives on the challenges that face us.

Sacred Hill was commissioned by the Nederlands Film Festival and The New Institute and supported by The Mondriaan Fund, Fund Creative Industries NL, Film Fund and the AFK. During the Amsterdam Museum Night Sacred Hill the VR can be experienced Saturday 2 November 19:00–02:00

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.