A still from

Keiichi Matsuda’s short film, Hyper-Reality

(2016)

A still from

Keiichi Matsuda’s short film, Hyper-Reality

(2016)Keiichi Matsuda’s 2016 Hyper-Reality remains one of the most concise indictments of the capitalist imagination that I have seen. In this crowdfunded futuristic vision of augmented reality gone wild, no experience, no matter how quotidian, is safe from transactional logics. The streets of Matsuda’s Medellín, like its busses and grocery stores, are supersaturated with an information overlay, interpenetrated with commercials, and insistently driven by gamification.

Sadly, this vision of augmentation in public spaces is alive and well in Anno 2021. A Google image search for “augmented reality” offers a glimpse into status quo thinking about augmented reality that largely replicates Matsuda’s tropes, minus the gusto. Fortunately, a counter movement has taken hold and is surging.

A new generation of artists, activists, and documentarians has entered public space, armed with the possibilities of emerging technologies as well as long-established techniques for augmenting, documenting, confronting, and shifting our cultural narratives. From large-scale projections that draw attention to gentrification, to mobile apps that augment the meaning of statues and streets with unfamiliar stories, to location-based audio that highlights the effects of climate change, public space in these scenarios offers a platform for expression and transformation.

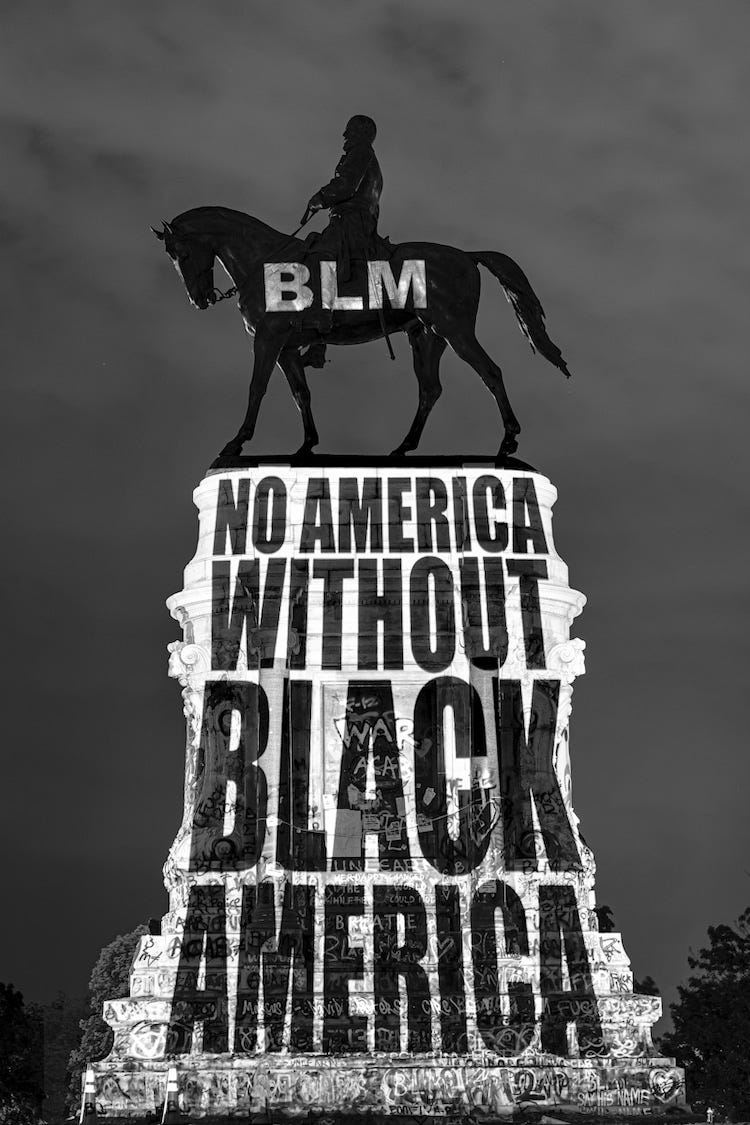

Artist Dustin Klein created light projections

targeting the Robert E. Lee statue in Richmond, VA. Klein’s collective, Reclaiming the Moment, aimed to “challenge

dominance narratives around historic memory.” In response to controversy surrounding the statue,

Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam issued a state order for the memorial’s removal, and it was dismantled n

September 2021

Artist Dustin Klein created light projections

targeting the Robert E. Lee statue in Richmond, VA. Klein’s collective, Reclaiming the Moment, aimed to “challenge

dominance narratives around historic memory.” In response to controversy surrounding the statue,

Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam issued a state order for the memorial’s removal, and it was dismantled n

September 2021Public spaces resonate in particularly interesting ways when overlaid with stories and images that are specific to them, making visible normally occluded conditions and layers of time. That, in any case, is our hypothesis. Indeed, thanks to a battery of augmentation technologies, public space is poised to serve as a robust platform for documentary and journalism, reality-engaged media that are too often cloistered, fire-walled, and site-agnostic. In this scenario, public space may well emerge as a platform for new forms of public media rather than simply morphing into the advertising industry’s next frontier.

The triad of augmentation, public space, and reality-based media (documentary and journalism) forms the core of a two-year research initiative that MIT’s Open Documentary Lab and Co-Creation Studio are conducting together with IDFA DocLab’s Research & Development Program. This endeavor is as concerned with the work of individual practitioners, many of whose work is supported by IDFA DocLab, as it is with mapping a space of intervention for the larger field.

Slippery terms

The astute reader may have noticed some slippage between ‘augmented reality’ and ‘augmentation’. Microsoft/Hololens and MagicLeap have spent small fortunes to convince us that augmented reality (as in AR) is a proprietary headset-based technology as cumbersome as present-day VR, with the difference that the external world peeks through. But this leaves out any number of established augmentation practices, from location-specific audio to phone and tablet-based systems to building-scale projection, not to mention analog systems (signage, for example). True, most media technologies enjoy some definitional imprecision (does VR include 360 video?), but when it comes to slippage, augmentation is in a league of its own.

Who has not walked down a street, phone in hand while following a map, looking up an address, or attending to some urgent business? These scenarios, some location-related and some not, effectively augment and transform the experience of moving through space. The term augmentation literally means enhancement through addition, and, as the research project uses it, goes far beyond the industry’s narrow sense of AR to include many other approaches to annotating the world, past and present, visual and acoustic, digitized and not. Augmentation is a concept-in-motion, caught between the narrow needs of investors and the wide-ranging uses made by cultural practitioners. And, at least in this expanded definition, it is nearly ubiquitous, allowing it to fade into the scenery even while shaping our experience. This gives it significant power while making it difficult to perceive.

The power of place

What happens when media and place combine? A tradition stretching from the caves in Lascaux and temples of Luxor to the latest Diller, Scofidio + Renfro creation suggests one compelling way to consider the question. But when it comes to screens, with the exception of drive-ins, we tend to be agnostic about where we consume our media. Of course, the quality of exhibition conditions matters, as does the character of particular venues, as does spectator habituation and preference. But the issue of where, in a geo-locative sense, the image takes form on screens big or handheld for the most part simply doesn’t matter. Screen cultures, although always local, are surprisingly ambivalent in their demands of the relationship between place and text.

The ability to layer image and sound on particular locations enables a dialogue between text and place, and herein lies the great added value of augmentation for documentary and journalism. This dialogue can happen in a directed though non-specific manner, as in Anagram’s Messages to a Post-Human Earth, Duncan Speakman’s Only Expansion, and Bart van de Woestijne’s In Order of Disappearance. In these cases, certain attributes of a location are required (under a tree, near a busy street…), but those can be found in a park, a built installation, or in most urban settings. And sound and image can be conjoined to space in a location-specific manner, as in Halsey Burgund and Sue Ding’s sound installation One Square Mile (on the site of the Manzanar National Historical Site, a WW2-era internment camp for Japanese-Americans); Michel Lemieux and Victor Pilon’s building-scale projections of key moments in Montreal’s history, Cité Mémoire, in old Montreal; and Dustin Klein’s projections of George Floyd on the Robert E. Lee statue in Richmond, VA.

Location matters in these and the many projects like them. It creates resonance with the extended world, both packing a punch by connecting the represented (the text) to the real (the site), and layering a particular spot in the world with meaning. Documentary and journalism, in this way, shift from their usual monolog to a dialog with the material realities on which those forms are based. And that is a significant and powerful shift.

Toward a new public media?

Recent developments in augmentation technologies have prompted growing interest in public space as a platform for digital storytelling, providing opportunities to make visible the invisible and reframe the way we imagine our communities. Precisely because they are dialogic, these developments offer an opportunity to reconsider and expand the ranks of who annotates public spaces. And they call to mind a deeper history of augmentation and urban annotation, from commemorative plaques and projections to shadow dancing and graffiti, that can inform our thinking about the latest augmentation technologies.

How can artists, storytellers, and cultural institutions co-create with their communities and foster dialogue about their public spaces, augmenting people’s experiences and in the process making public spaces more equitable? How can we make our public memorialization processes more reflective of diverse communities and more democratic? How can we use augmentation technologies to reveal artifacts and cultures that have been/are in the process of being erased?

Lots of questions, but that’s the nature of a research agenda. The Open Doc Lab will continue its conversations with leading thinkers, practitioners, and technologists in the sector.

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and Dot Connector Studio, and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.