James T. Green adapts a talk given at UnionDocs’ 2020 Podcast School, exploring time and space in experiential stories

by James T. Green

Originally published on Green’s personal site.

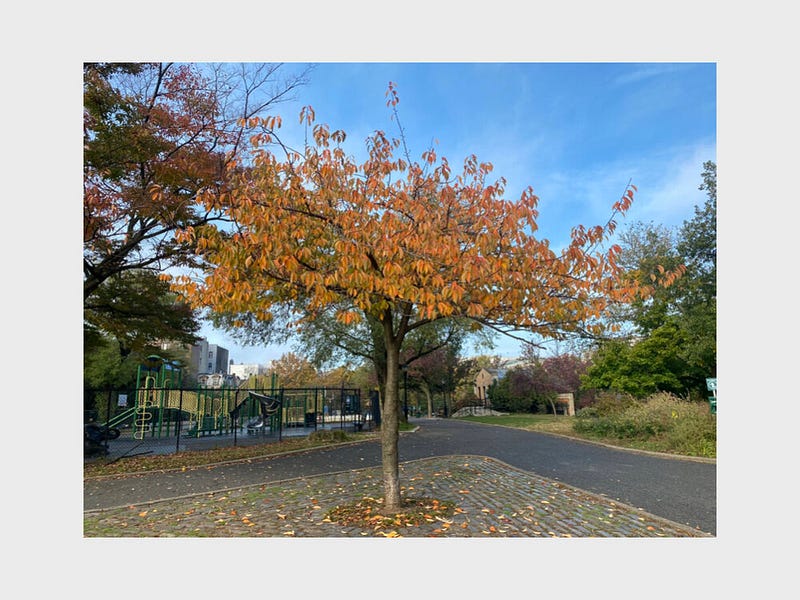

I want to start this talk beyond the Zoom windows and into a physical location. This talk begins in Brower Park. Brower Park is a local park in my neighborhood of Crown Heights, Brooklyn. It used to be called Bedford Park and was “purchased” in 1892. It was named after the Brooklyn Parks Commissioner George V. Brower.

Photograph of a historical marker

of Shirley Chisholm Circle in Brower Park

Photograph of a historical marker

of Shirley Chisholm Circle in Brower ParkDecades later, at the top of the park, a paved circular terrace alongside Kingston Avenue was named after Shirley Chisholm. Even though Brower Park had been in the neighborhood for decades, I became acquainted to it recently in 2020.

Brower Park was mostly a footnote in my life — a place I passed through when I got off the B43 at Brooklyn Ave and Park Pl. Like many in 2020, I got to know the space outside of my home. I don’t have an outdoor space connected to my apartment, but the park was the closest thing.

The sonic landscape on the way to the park is varied. I’ll walk out my door, and street traffic swirls around me. Maybe I’ll hear someone arguing with their special someone over their car’s speakers and I’m immediately invited into their conversation. I cross the street and more people’s soundtracks become my own. I look to my right and the giant brick facade of the Hebron SDA school greets me. A flutter of fliers attempting to save its fate from condos pocket the chainlink fence.

I walk down an uneven sidewalk. The scent of dog shit reaches beyond my mask. I sidestep to the right and the crunch of a Fendi receipt crinkles under my shoe. The traffic from Brooklyn Avenue grows nearer, and the space in front of me roars alive. Garbage trucks, ambulances, and amateur drag racers zoom the empty streets like a highway. Grand Theft Auto, but real life.

I cross once, then twice, and enter the park. Somedays, it might be raining.

Three overlapping photographs of

a park path, trees and a daffodil

Three overlapping photographs of

a park path, trees and a daffodilThe trees dampen the sounds of human intervention. The sensation of rubber sneakers on pavement reverberate through the cavities of my body. Ballers, boarders, and burpees take over the pavement to my left. The squeals of playground swings share the frequencies of children screams.

A circular grassy area is the park’s center piece. The Shirley Chisholm Circle frames it like a crown. Surrounding the parks are benches shared by 30-somethings like me, Hasidic summer campers, aunties searching for Key Food coupons, and a saxophonist that’s been practicing a familiar sounding melody.

Eventually, I find a bench. Then, I’m faced with a decision. Do I want to exist in this world in front of me, or escape to another one?

Two photos: the one on the right

depicts a caution sign posted on the chainlink gate of a park playground and the one on the left

depicts a park bench, photographed from above

Two photos: the one on the right

depicts a caution sign posted on the chainlink gate of a park playground and the one on the left

depicts a park bench, photographed from aboveOnce my headphones are in, augmented reality takes over. I traverse different planes, time periods, and timelines. The present tense of the saxophonist practicing scales and Dean Street parents cycling their kids to the playground still exists, but my attention is split with recordings from a point in history. These simultaneous contexts are forever in conversation with each other. Much like the historical context of the park, I’m in forever pushing against the past, present, and future.

Usually, I’m not the only one existing in augmented reality. On the benches around me, someone is taking a phone call — an act of present communication breaking the barriers of space. The saxophonist is practicing along to a reference track in his headphones — recalling a historical recording and interpreting it in a present place while rebroadcasting his live interpretation for a present audience. The drummers in the distance are channeling their ancestors through the rhythm in their fingers which then gets shared to me.

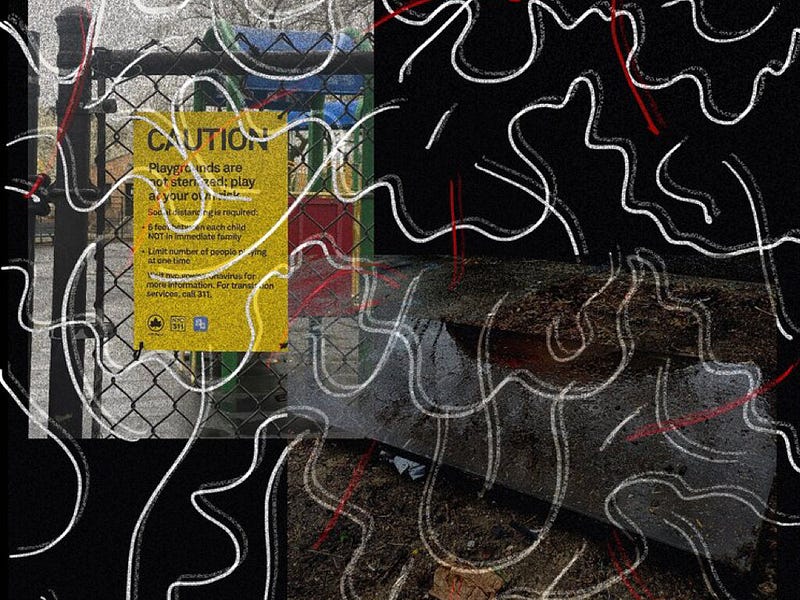

How does sound react to materials in space?

Text reading “how does sound

react to materials in space?” overlays a photo of an empty park playground, viewed through a

chainlink fence

Text reading “how does sound

react to materials in space?” overlays a photo of an empty park playground, viewed through a

chainlink fenceThis made me interested in how sound reacts to physical space and how one interprets it. Listening to that saxophonist practice — which I have because he lives on my block — through the windows of his home from the street unlocks a different interpretation than hearing him in the public space of Brower Park. The former is a result of private space leaking into the public. The latter is a public space attempted to make private, which in turn becomes an unlikely performance with passersby. Anything that others do in the public space will be in concert with his practiced song. If someone is on the phone with a friend in the park, it will be soundtracked by his practicing, and he will become an unlikely participant in the conversation.

This even extends to my private head-phoned world. If I listen to music in the park while the saxophonist practices, the gaps of silence will be filled by his playing. This will create a one of a kind composition, one that is private to me and can no longer be recreated.

Creating silence for the sake of interplay with the public

Text reading “creating silence for

the sake of interplay with the public” overlays a photo of a trees and a park bench reflected in

water on a path

Text reading “creating silence for

the sake of interplay with the public” overlays a photo of a trees and a park bench reflected in

water on a pathThis got me thinking about how songs play with the idea of silence as part of their composition. A contemporary example I could think about is Ariana Grande’s “get well soon.” The last track on the album Sweetener features a 40 second moment of silence which pushes the song’s length to 5:22. This was crafted in honor of the victims and survivors of the Manchester Bombing at her May 22, 2017, concert.

Especially in the age of endless streaming, silence — intentional or accidental — is a rarity. Its execution is noticeable when it’s implemented. If autoplay is enabled after that song, an extremely punctuated period of silence is maintained before hearing the next thing in your queue.

When Ariana’s moment of silence occurs in the final mix, her vocal echos are reminiscent of a live performance, filling the soundstage of headphones that would have been shared physical space at a concert. This leaves a private moment with the listener where background noise becomes both part of the composition and listener’s private moment of reflection.

When in shared space, a moment of silence is powerful. I think about the moment of silence held by Emma Gonzalez at the 2018 March for Our Lives Rally in Washington. At the rally, Emma — a survivor of the 2018 Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida — stood on stage for four minutes and 26 seconds after a brief two minute speech. Her total elapsed time on stage mirrored the time spent by the shooter during the mass shooting.

Photo of blue-painted wooden

police barriers on the ground, bearing text reading “Police Line — Do Not Cross, NYPD.” “Cross” is

crossed out and replaced with “Shoot” in red paint. “Black Lives Matter” is also painted in

red

Photo of blue-painted wooden

police barriers on the ground, bearing text reading “Police Line — Do Not Cross, NYPD.” “Cross” is

crossed out and replaced with “Shoot” in red paint. “Black Lives Matter” is also painted in

redMoments of silence have become even more present now with the current movement for Black Lives. At many marches, the silence generated is as important as the noise, allowing space for reflection to fill the mind. Especially, in the age of the attention economy, creating space is just as important as filling it.

Soon after George Floyd, Brianna Taylor, and all the countless others that have been harassed and killed by white people in the past couple of years, I’ve thought about silence a lot. Silence in policy, silence in complicity, silence in the literal of silence of voices once murdered. In response, I created “for george, breonna, ahmaud, and christian” — a piece to create my own silence.

The flourishes of Moses Sumney’s “colouour” felt like rising hope — the positive feelings of what it means to be Black. My voice felt like a humming heartbeat, mirroring the monotonous and repetitive sensation of just trying to get through the day. The sudden stop felt like the unexpected silence of voices that aren’t given a chance to continue, and cultivating that silence in the piece’s mix instead of ending the file abruptly created a forced physicality. A barricade of silence is created for those listening, allowing their own thoughts to fill the rest of the space before the next autoplay or queue item in their listening diverts their attention elsewhere.

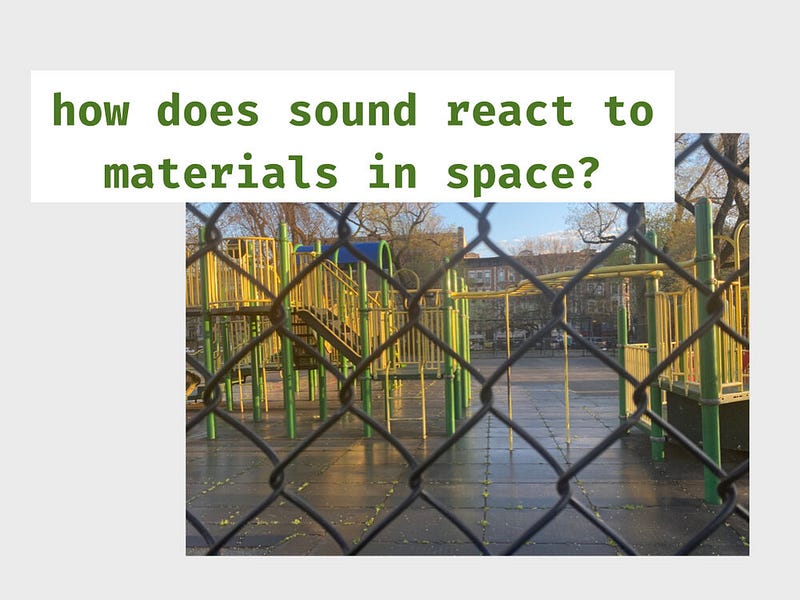

Photo of a tree, whose leaves are

turning orange and yellow, at the intersection of two paths in a park

Photo of a tree, whose leaves are

turning orange and yellow, at the intersection of two paths in a parkBack at the park, as I continue to exist between multiple layers of sound and dimensions, I think about the different layers of reality people are living in at any given time. Especially in the lens of accessibility.

I think about Christine Sun Kim’s piece, Closer Captions. In it, I felt the relationship between the silent human labor of transcriptionists and those like her engaging with the works — similar to the Brower Park saxophonist that is interpreting a past work, playing it in his own interpretation, and myself the listener trying to figure out what tune he’s practicing.

Christine does an interesting thing where she’s playing with three dimensions of sound interpretation. There’s the sound itself. Then there’s the person’s interpretation under the guise of technology. Then there’s the person reading the caption and interpreting what the interpreter is trying to communicate.

These multiple dimensions make me think of Eleanor McDowall’s Field Recordings project, where you listen to field recordings made by audio artists. There’s no flourishes or introductions, you’re just thrown into a different environment. What does it mean when you’re listening to a park in Tokyo while you’re seated in a park in Brooklyn? Listening to the tape of the crickets and fountains, can you envision where you are in space? How close are the crickets? Are you so close to the fountain that you might get wet? Do you feel safe as a listener?

Three overlapping photos of the

Studio 54 exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum, which is strikingly lit by bright neon lights emulating a

nightclub. There is text reading “press photos of the exhibition” at the bottom of this

collage

Three overlapping photos of the

Studio 54 exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum, which is strikingly lit by bright neon lights emulating a

nightclub. There is text reading “press photos of the exhibition” at the bottom of this

collageRelated to this, I think about an early form of virtual reality: museum exhibition design. Particularly, I was reminded about a recent trip to the Brooklyn Museum for the Studio 54 exhibition. Studio 54 was a former disco night club in New York that was frequented by folks like Grace Jones and Andy Warhol. Upon walking in the exhibition, you’re overtaken by the time period through sounds and visuals. It felt even more dramatic visiting an immersive exhibition about close bodies chasing pleasure in the middle of a pandemic.

Walking through the exhibition felt like following a timeline of ephemera. Every sense with the exception of taste and smell were activated. Arguably, touch was activated through feeling the bass of the room’s soundtrack. In the middle of the exhibition, I found myself crying because I forgot where I was, mentally, physically, and spatially. Through the complete immersion of this exhibition, my body and mind played a trick on my conscious. This act of immersive design transported me away from a dark 2020 and for two hours, I lived a fantasy through documentary art.

In a similar vein, I created a piece thinking about space — physically and metaphorically. I’m very curious about space as a framework, particularly how it exists in audio. I was drawn to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as a piece of pop psychology but as a mental space that people could categorize themselves into. This led to the piece “Maslow” which I created for BBC Radio 4’s Shortcuts.

I thought of Maslow’s various levels as rooms in exhibition design, and once a listener enters those rooms, you’re brought into a new scene where they can project their own experiences. I wanted the piece to act as window dressing for a listener’s subconscious.

Three photos cascade from top left

to bottom right, featuring a bird standing next to a plastic bottle of water on a park bench, a

discarded doll on the ground in front of two tennis-shoe-clad feet, and a squirrel perched on the

edge of a trash can

Three photos cascade from top left

to bottom right, featuring a bird standing next to a plastic bottle of water on a park bench, a

discarded doll on the ground in front of two tennis-shoe-clad feet, and a squirrel perched on the

edge of a trash canThis takes us back to the park. Whether I’m seated on the bench or walking around the loop of the park — headphones in or headphones out — there’s two things that are always happening. My attention is drifting between internal contemplation and external stimuli. Also, my spatial relationship in the park is always changing. My body is interacting in shared space with humans, animals, and plant life. If I’m walking with someone, my conversation intertwines with the conversation of strangers.

These are things I think about when creating stories. I’m uninterested in lecturing to the listener. I’m more interested in creating a shelter or a framework for the listener to enter and fill in the gaps themselves. It’s similar to setting the mood of a home before a visitor arrives. You’ve lit the correct candles, you’ve arranged the furniture, and you’ve made a space for those to be in conversation with your work. The work becomes a jumping off point for meaning, rather than a closed loop with no other interpretation except the straight line that has been drawn.

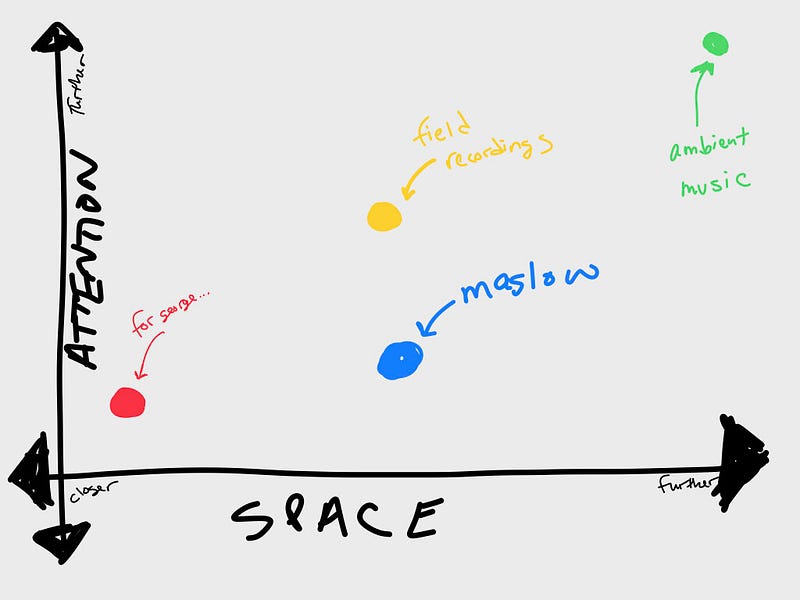

I believe that can be achieved by thinking about works in the following chart, along the axis of Attention and Space.

A hand-drawn graph: the x-axis is

labeled “Space” from closer to further, and the y-axis is labeled “Attention” from closer to

further. There are four different colored dots on this graph. “Ambient music” is in the top right,

furthest in attention and space. “Field recordings” and “Maslow” are both in the middle of the

x-axis of space, but “field recordings” is further along the y-axis for attention.

A hand-drawn graph: the x-axis is

labeled “Space” from closer to further, and the y-axis is labeled “Attention” from closer to

further. There are four different colored dots on this graph. “Ambient music” is in the top right,

furthest in attention and space. “Field recordings” and “Maslow” are both in the middle of the

x-axis of space, but “field recordings” is further along the y-axis for attention.With audio works as dots on the chart, its awareness of listener attention and spatial awareness glides along. I ask myself these questions:

How close attention should the listener be paying attention to a certain thing (the tracking that is delivered, the ambi filling the scene, etc.)? Where is the listener in the space you’ve created for them? Is the listener fully embedded in the scene you’ve made? Are they a main character in the story or a bystander?

I don’t believe there’s one right answer, but playing with the dot’s location and having it exist in different locations in a single story can lead to more dynamic work, much like the dynamism of moving through space in real life.

Story techniques as design systems

Text reading “story techniques as

design systems” overlaps with two photos, the one on the left of two parallel contrails, and the one

on the right of two pairs of semi-transparent jelly sandals sitting on a ledge

Text reading “story techniques as

design systems” overlaps with two photos, the one on the left of two parallel contrails, and the one

on the right of two pairs of semi-transparent jelly sandals sitting on a ledgeBefore professionally working in audio, I was formally trained as a conceptual artist and digital designer. Through conceptual art, I think a lot about the journey of thought, and the pathways and connections people make when connecting ideas, and how those journeys lead to an interpretation of a piece. Through digital design, I thought a lot about how people travel through digital space, such as the journey someone takes during their interaction with a model or object.

Whenever I opened up an Adobe Illustrator document, I was faced with a dialogue box asking for the attributes of the document before I was allowed to create. How many pixels wide by how many pixels tall. Usually that’s a common aspect of working in digital systems. You’re creating the canvas and the bounds you’re working in before you get started.

For visual design, or visual art for that matter, space is a common metaphor. With audio, space is interpreted through frequencies and layers in the mix, but one of the stronger metaphors we lean on in audio is time.

In 2020, time feels strange. For the majority of people that spent most of their days moving around various locations, our spatial signposts have collapsed. What does a commute mean when now it’s the seconds between thinking about a task and picking up your phone instead of the time it takes to move your body from one structure to another?

Thinking about grasping onto the structure of time, I think about a piece made by artist Adrian Piper. In 1968, she created a piece called “Seriation #1” in which she recorded herself dialing into a phone line that announces the time.

This gesture feels like a challenge to time itself. The service promising to announce the current time is in fact, not real time, because the moment the automated recording delivers the time, it is out of date. The nature of real time is a construction. This led me to the following theory:

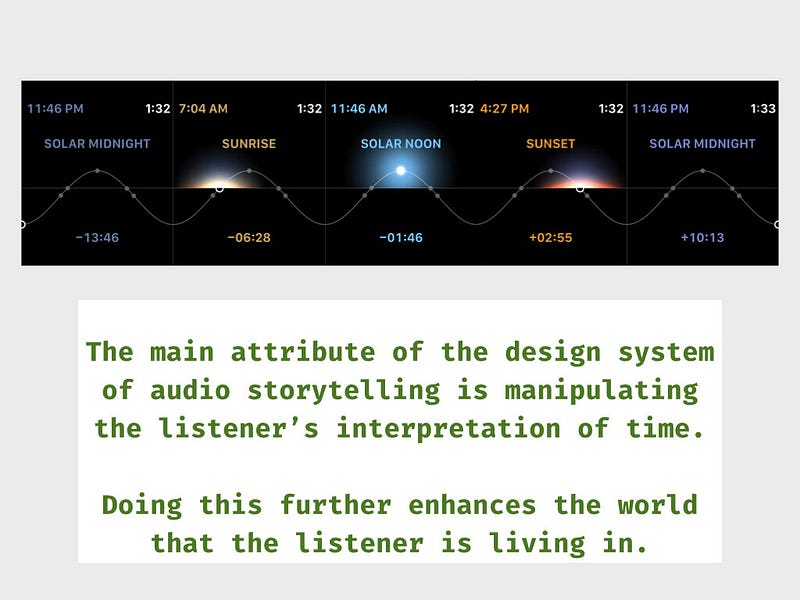

The main attribute of the design system of audio storytelling is manipulating the listener’s interpretation of time. Doing this further enhances the world that the listener is living in.

Image of a solar graph with text

labeled “solar midnight,” “sunrise,” “solar noon,” “sunset,” and “solar midnight” to their

corresponding times

Image of a solar graph with text

labeled “solar midnight,” “sunrise,” “solar noon,” “sunset,” and “solar midnight” to their

corresponding timesThis got me thinking about how time exists on a standard day. On a solar graph, there is solar midnight, then twilight, sunrise, day time, solar noon, sunset, then another form of twilight, night, and then solar midnight all over again.

This very organic relationship to time is similar to the construction of Ela Minus’ “dominique”.

The construction of song, down to the signposting of location (today/tonight, coffee/liquor, am/pm) give a sense of existing in one day. Even down to the elements of the song, with repetitive elements that come in at predictable times while falling and rising in density and complexity evoke the changing nature of a single day. If you listen to the song on repeat, the six seconds of silence at the end lead wonderfully into the first word “today” feels like living a day, over and over again.

Even though the song is only a little over three minutes, it mirrors the organic, earth-bound world of seasons with rising and falling energies, evoking real time metaphors.

Both of these works were in mind during the creation of my piece “bedkitchendesk”.

In “bedkitchendesk”, I thought about the framework of time, and how to make something that both advances in time but also feels claustrophobic. Repetition is a great technique to bend time for listeners. Thinking about repetition in real time, I think of the piece Crip Time, by Carolyn Lazard.

A lot of Carolyn’s works play with the perception of time through the lens of her chronic illness. Crip Time, in particular, plays with multiple degrees of time: time in the sense of how the work is being presented (an edit that exists just over 10 minutes), time in the future (how she will later ingest these meds throughout the week), and time in the structural sense (a physical representation of days by the amount of pills that are dedicated to each day).

While watching her piece, I can’t help but be drawn to the rhythm of the experience. You could argue that the 10 minutes in which the piece exists completely vanishes, like how one falls in an algorithmically fueled K-hole powered by “oddly satisfying asmr” videos.

In my perspective, Carolyn’s piece exists in both real time and “hyper-time”, in which the viewer’s sense of time is completely disoriented. Repetition in this sense is key to establishing this disorientation. It’s arguably why quarantine has distorted our sense of time, especially pairing this with spatial collapse.

Thinking about distorted time fueled by repetition, I thought about contemporary examples that rely on this technique, and I thought about Post Malone’s single “rockstar,” and its story to the top of the Billboard Hot 100 in 2017.

According to The Fader, Post Malone’s label, Republic Records, uploaded a YouTube video that features the chorus of the song on a loop for 3:38, the same length of the full song. While this was a hack, because streams on YouTube count towards Billboard numbers, people that come to the YouTube video looking for the full song will have to later go to Spotify to listen to the full song. This led to a two in 1 stream.

But I’m less interested in the hack, and more interested in the satisfaction that comes from the chorus’ repetition and how in turn it paints the thesis of the song. A seamless repetition of the song’s chorus, blends the listener into a spaceless stupor.

It feels like a drug trip without drugs. It feels like being a rockstar without leaving your bedroom.

The construction of the song, with its minor key and descending repetitive melody, immediately captures a listener in the orbit of the world. There’s no sense of time in the lyrics — no signposts of today/tomorrow/yesterday. There’s no markers of day or night, everything blends into one another. Unlike Ela Minus’ song with its clear tick-tock of time, Post Malone feels like a muddied hyper-time where events have no sense of place. We don’t even know if we are existing in a memory of the narrator’s past, existing in a debaucherous present, or looking at an imagined future.

Both Post Malone’s and Ela Minus’ narrators exist in a darkness, grasping for control in a repetitive situation. This is similar to the works of Adrian Piper and Carolyn Lazard. While the four artists used different techniques, they all bended the perception of time to advance their narrative.

In the spirit of those works, a recent work of mine created for the podcast Constellations, uses repetition to disrupt the listener. In the piece “EMDR”, repetition is a method that lulls a listener into its cadence. The voices of myself and my partner above the repetitive hum places us in a domestic space and time existing in real time. Later, the repetitive voice plays into the real time metaphor by relying on the actual time limitation of the human breath, trying to complete a refrain but fails due to a lack of oxygen. The hyper-time that control promises evaporates back into real time.

That leads to my last thought on the design systems of audio stories.

Time as canvas, journey as artistic gesture

Text reading “time as canvas,

journey as artistic gesture” overlays a closeup photo of an bitten apple sitting on a park

bench

Text reading “time as canvas,

journey as artistic gesture” overlays a closeup photo of an bitten apple sitting on a park

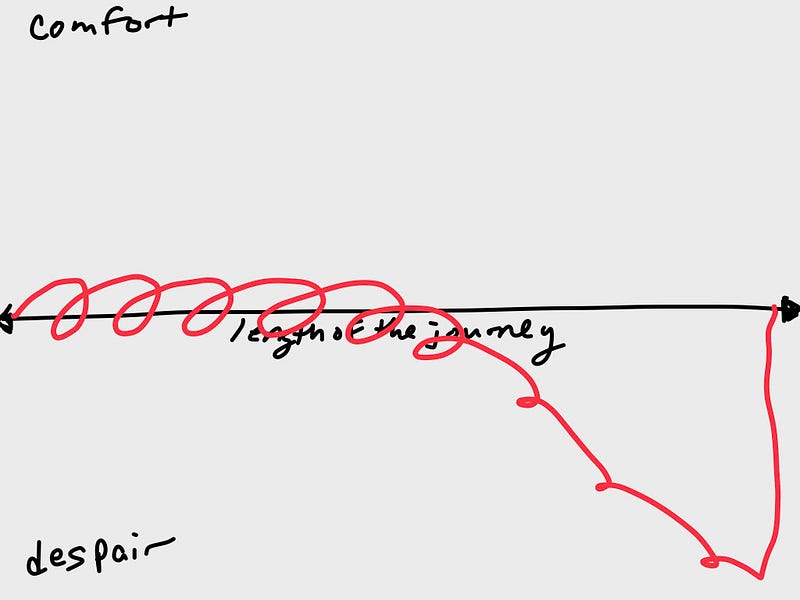

benchTime is the canvas of the work, and the journey of the listener is the gesture on the canvas. The bounds of the runtime is the length of the journey of the listener’s experience.

It’s the framework you’ve provided the space to exist in. The journey that exists across that length of time is the artistic gesture across the canvas.

The beauty in story arcs for experiential works are that they are more reliant on listener interpretation, which means while the framework is the same, no story arc will be the same for each listener. In these kind of works, the listener is both pilot and co-pilot of the story.

Here is an example of my personal time/journey chart I created for EMDR — shout out to Kurt Vonnegut. My interpretation of the journey is cycling through an even period of comfort and despair over a set period of time, before the character devolves into despair. Near the end, the line shoots back up to its starting point because the character becomes aware of their despair, resulting in a stable state.

In closing, much like how I interpreted Christine’s Closed Captions, humans do not respond to sound like software, purely representational bits of ones and zeros. Our interpretations are messier. We naturally editorialize as living organic matter. If something is pleasant, we may linger in it a bit more. We might even repeat the activity, like the joy of continuing to eat a dish of delicious food. It’s why a chorus of a song is so intoxicating. You’re hearing the best part of the song multiple times. On the other side, if something is hurtful, it may occur suddenly out of nowhere. Many times, fear and pain comes from the unexpected, much like cutting out the signal of a voice in a story and living in a moment of silence at the end of a work. That’s a much more effective technique than simply saying, “I am scared,” or “I am fearful.”

When thinking about spatial awareness in the terms of audio work, it’s important to think beyond the technical, like how far or close certain things are in the mix. Also consider its conceptual relationship to the real world.

How does it feel when pleasant sounds are closer? How does it feel when pleasant sounds are far away? How does that change when the sounds are in real life, versus something you choose to escape to in headphones?

As the architects of the worlds that people are escaping to, it’s important to not only consider the physical design of the worlds, but how the humans in the worlds will interact with it.

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.