Artist WhiteFeather Hunter creates beautiful things by growing bacteria, chatting with bugs, and collecting menstrual blood

WhiteFeather Hunter is a Canadian bio-artist and scholar who works with microorganisms to create gorgeous textiles and other inventions. Hunter describes her work within “the frameworks of craft, feminism, witchcraft, and relationships with nonhumans or nonhuman organisms.” Katerina Cizek conducted this wisdom for Collective Wisdom. To see more of Hunter’s work, visit her website.

Katerina Cizek: Is co-creation a term you use? How do you define it?

WhiteFeather: “Co-creation” is the term I prefer over “collaboration.” I’m very careful where I use that term.

Can you elaborate? What do you mean?

For me, “collaboration” implies consensual involvement of two or more parties working towards a shared goal.

I use “co-creation” or “co-construction” when working with a broader range of living organisms — for example, artworks with an animal participant. There’s an ethical conundrum when the other collaborator is forced to be there. I would avoid calling that collaboration. Co-creation acknowledges that they have some agency in the process, but it’s not taking for granted that they’re there of their own free will.

So, co-creation does not assume consent?

I don’t think so. Someone else could use the term differently, but that’s my way of negotiating that tricky issue.

In other words, you collaborate with humans, but you co-create with microorganisms?

Yes.

Petri

dishes of Vogesella indigofera growing on menstrual blood agar (Bactinctorium project with Gen

Moison, Vanessa Mardirossian, and Alex Bachmayer).

Petri

dishes of Vogesella indigofera growing on menstrual blood agar (Bactinctorium project with Gen

Moison, Vanessa Mardirossian, and Alex Bachmayer).Interesting. You’re the first person I’ve interviewed to use the term that way. What non-human systems do you work with?

I have worked primarily with human cells, other animal cells, as well as bacteria cells towards developing new types of biomaterials.

What kinds of new biomaterials?

Anything that falls within the realm of what I call biotextile. That includes growing living layers of flesh, for simplification’s sake, on a textile scaffold as well as developing new forms of bioplastic using bacteria cellulose. I can treat it with a formula to make it more resilient and generate new textile dyes using pigment-producing bacteria.

You’ve worked with bioluminescence as well. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

I worked with Vibrio fischeri, which was very tricky. It’s a finicky organism. I tried developing a cheap DIY nutrient media for it from chicken broth, but I could never quite get it happy enough to do what I was hoping it would do. I wanted to create bioluminescent lace by growing it on the lace. Some bacteria don’t want to grow on a textile substrate. This was one of the species that didn’t want to co-create with me. I abandoned that project for now.

Can you talk about some bacteria that you feel DID co-create with you?

Well, it’s important to recognize the inherent properties of a bacteria species. One that I’ve worked with is Serratia marcescens. It’s known as pathogenic, but I managed to get a nonpathogenic strain to work with.

How is it pathogenic?

It grows rampantly in hospitals and feeds on soap scum. It will grow in your shower if your shower isn’t regularly cleaned. It appears as this pinkish slime.

In hospitals, it’s a problem because it can cause lung infections and urinary tract infections and other complications for patients recovering from weakened immune systems. I think the concentration found in our bathrooms probably isn’t much of a problem.

A strain that I’ve been working with retains all of the characteristics of the native strain except that it’s been adapted to be nonpathogenic. It’s still extremely aggressive and resilient. So, I’ve been able to grow it and concentrate its pigment on different fabrics and use it as a printing medium.

It takes the characteristics that would normally be villainized in an ordinary biomedical context and turns it into something useful and beautiful.

How did you use it as a pigment?

I was growing it directly on the fabric as well as on an agar substrate. I can use it with stencils to print patterns onto fabric. It makes a really lovely, deep red dye.

Another bacteria species we’re working with is Vogesella indigofera. This is a common freshwater species. It’s sometimes found in contaminated water. It’s another pigment-producing bacteria, only this produces indigo molecules. The amount of water being polluted has become a crisis in the fashion industry, so this is a potentially problem-solving area of research. I don’t do my research to try to solve human problems, though. I’m careful not to make those sorts of promises.

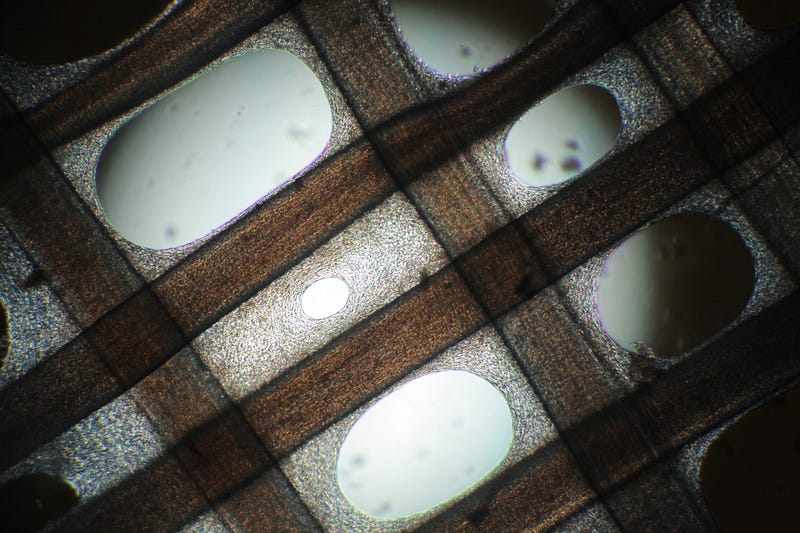

I’ve worked with a variety of human and mammalian cells. I’ve studied cells’ inherent behaviors and how to influence the way they grow by using different materials. It was really nice to discover that the intersection points — or the axes where threads are crossing over each other in a woven cloth — became information axes for the cells, where they begin to collectively build bridges.

I’ve noticed a lot of organic systems work this way, including plants, where they find a shortcut and start building and proliferating from there. I was interested in that not only for the biomaterial capacity but also for the more philosophical aspects of what it implied.

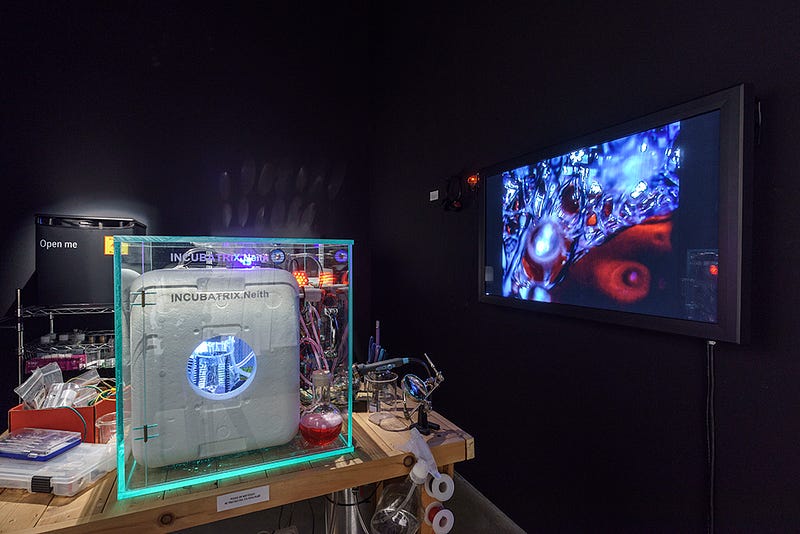

Installation of live biotextiles (mammalian cells on handwoven scaffolds) inside

a DIY CO2 incubator, housed within a Biosafety Level 2 laboratory in the Black Box of the FOFA

Gallery, Concordia University, Montreal. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

Installation of live biotextiles (mammalian cells on handwoven scaffolds) inside

a DIY CO2 incubator, housed within a Biosafety Level 2 laboratory in the Black Box of the FOFA

Gallery, Concordia University, Montreal. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.Can you talk a little bit more about that? You have mentioned witchcraft as well. How do those things connect?

Witchcraft is, for me, synonymous with feminism — two branches on the same tree. But it also has this wonderful aspect of magic, a way of negotiating the unseen and sometimes unknown natural forces around us. It’s looking at magic as an interface methodology, but it’s also poking fun at the fact that scientific methodologies often function to replace or fulfill a need similar to religion in terms of promising to explain human suffering or alleviate it or extend life. I see these things as common goals of both religion and biotechnology. A lot of scientific techniques and methodologies are appropriated from older folk knowledge. It’s all of that wrapped up into my approach that I’m labeling witchcraft.

When you’re working with these biomaterials, what surprises you? What are you learning?

I’m learning that just as I am relying on the activity and cooperation of these microorganisms, I also am relying heavily on an ever-growing community around me, mainly young women with similar research approaches and interests. My practice keeps expanding, a natural move when you gather more brains together.

Serratia

marsescens printed on silk.

Serratia

marsescens printed on silk.That’s been the approach at my lab at Concordia University. It’s been very successful and it’s been outside of the normative structures of academia because I’ve been doing it on almost no funding whatsoever. I’m not a faculty member and I’m not a student. I’m an anomalous presence that they tolerate because we are producing exciting things in the lab and it’s gaining attention and recruiting new students.

I’m learning to just stay humble because I can’t anticipate the results of this research. It’s very much a process-based art practice. So, I’m disseminating this research in a variety of different fields: community events, Ars Electronica, or a classroom of women recovering from domestic violence who they need a creative outlet. I’m not being picky about where I share this knowledge.

Can you talk a little bit more about the relationship you have with this biomaterial? What does your studio look like?

I work in three different labs right now. The one I’m running in Montreal at Concordia looks like a standard laboratory, but it’s got mannequins that we’ve pulled out of the garbage. It’s got kiddie pools that are filled with brewing kombucha so that we can grow large-scale cellulose.

I like to insist upon using empathy as a laboratory technique.

My relationship with the biomaterials is not very scientific. I like to insist upon using empathy as a laboratory technique. I have had to push my scientific collaborators to use, to embrace, to understand this idea. It’s a very basic thing. People who talk to their plants can get beautiful, luscious plants. I talk to my microorganisms. I try to communicate my thoughts and feelings about what they’re doing to them. In a way, that helps me identify with them a little bit. I anthropomorphize them. That strengthens the care and my personal investment. I find it essential. If the care is not there, the organisms can die. They can get contaminated. Then your research is out the window.

Microscopic

detail of a live biotextile.

Microscopic

detail of a live biotextile.You mentioned feeding earlier. What do you mean by that?

I feed them with my own body materials if possible. Standard laboratory materials often need special authorizations. So, I’m always looking for more accessible and feminist alternatives. The indigo-producing bacteria is an iron-loving species. My collaborators and I have been collecting our menstrual blood every month and diluting it to make blood agar plates. The bacteria absolutely love it! It’s producing the most beautiful deep blue.

The levels of bureaucracy that we had to go through to be able to handle our own menstrual blood in a laboratory was about a six-month process, including having to meet with doctors and explain to them why I didn’t need to get a vaccination to handle my own menstrual blood.

Not only is it a feminist approach, but it’s also commenting on the incredibly complex body relationships with all of these microorganisms. In a way, it’s also confronting our culture of sterility.

Are you involved in any computational systems in your work? Can you talk a bit about that?

To display the biotextiles in a gallery, I had to build a C02 incubator with a peristaltic pump system. I was hacking things together to build a protective cyborg body for these things. It became part of the care and maintenance to keep the organisms alive. This contraption was not only its body, but it was like a mother for it. I had to regularly visit the gallery to maintain this electronic organism as well as the mammalian cells.

It was really challenging because electronic systems fail a lot more than biological systems do. The peristaltic pump system was working like a stomach. It pumped the nutrient media in while another pump was sucking out and continuously circulating nutrients.

Eventually, the pumps got out of sync with one another. More fluid was being pumped in than was being pumped out. I had to do a little surgery on it halfway through the exhibition.

You talk about electronics as organisms. Do you consider them non-human systems that you’re co-creating with? Are there surprises that in creating those systems?

I’m certainly relying on them. The work won’t be able to live in specific contexts without the electronics. So, in that way, I guess I’m co-creating an exhibition with them.

It’s interesting because people are almost as afraid of electronics as they are of microorganisms. When I am negotiating with curators or gallery directors to display these works, they need a lot of reassurance. That’s often another level of bureaucracy.

People are almost as afraid of electronics as they are of microorganisms

Part of the reason I’m doing this work is to make this knowledge more accessible. I often find that people are afraid to touch anything. Artwork already comes with that baggage. You’re not supposed to touch it. But when I’m trying to extend the care and maintenance of these microorganisms and electronics to the gallery staff, I have to help them overcome their fear of working with the microorganisms and electronics. It’s necessary because I can’t be in the gallery every hour of every day.

Big, burly technician dudes setting up my work will ask whether or not they’re going to catch something life-threatening from the microorganisms. They’ll complain about a sore throat and think it’s caused by a vial of cells contained inside a box. There’s no way that’s possible. But the fear of these things is strong enough that they are manifesting physical symptoms.

Performing

the “aesthetics of care” with biotextiles in the Black Box

Performing

the “aesthetics of care” with biotextiles in the Black BoxDo you think a co-creative model offers the public an opportunity to think about these relationships differently?

Yes. I think that’s important. We’re so steeped in philosophies centered on humans at the top that we are alienated from other systems. That leads to fear and huge knowledge gaps. I think it has caused the trouble we’re in on a planetary scale right now.

Some of your work is speculative and offers a different kind of future. Can you talk a little bit about that?

I’m interested in flattening hierarchies in knowledge systems; I think that is absolutely necessary in order for any collaborative work to succeed. That kind of leveling needs to happen within academic institutions so that sequestered areas of knowledge start talking to each other. New forms of knowledge will emerge from this. That is the way things are going. I’m confident. A lot of institutions need to throw out their assumptions about the way universities need to work. It’s all wrapped up in funding. That’s often a stumbling block. Whose budget is paying for what when you have two completely different departments coming together to work on something?

I think there are ways around that. I think that artists can lead the way in that sense because we are extremely resourceful. We have to be. I think that women probably have the best capacity for working and thinking that way in general. That’s my future vision. Maybe at some point a university classroom will be led by a lecture that’s given by a group of microorganisms. That would be fun.

And on life support by cyborg in incubators, of course.

Right.

…being cared for by humans.

Yes. We’ll be their servants.

This article is part of Collective Wisdom, an Immerse series created in collaboration with Co-Creation Studio at MIT Open Documentary Lab. Immerse’s series features excerpts from MIT Open Documentary Lab’s larger field study — Collective Wisdom: Co-Creating Media within Communities, across Disciplines and with Algorithms — as well as bonus interviews and exclusive content.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.