Player choice and narrative strategies in essay games “1979 Revolution: Black Friday” and “Attentat 1942”

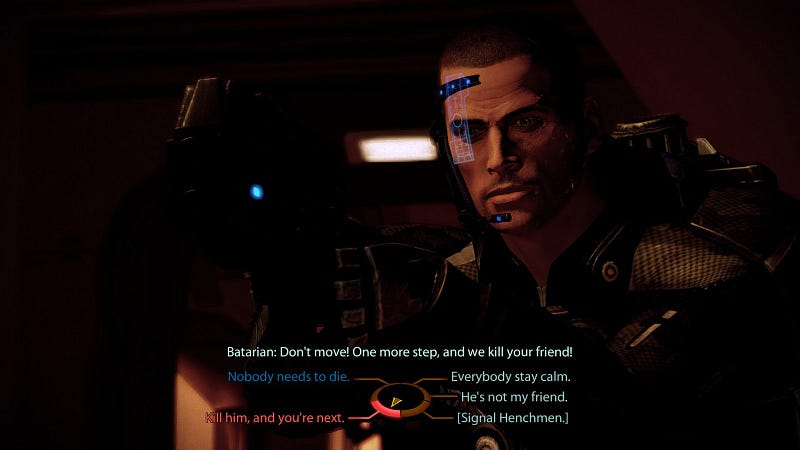

Player choice within contemporary video games has become a design staple across the industry. Choice can manifest in a variety of different ways: equipment loadouts, morality engines, navigating a level’s objectives, and character customization. But often when designers and critics talk about “choice,” it’s in relation to how the narrative design allows for player input to have tangible consequences. In a game like Mass Effect, for instance, choice shapes how the player “plays” as Shepard (the game’s protagonist) — choosing which teammates come on side-missions, dialog options that shape the narrative, or which NPCs to seduce — it’s up to the player to choose how they want to play.

As a compelling alternative to Mass Effect and other mechanistic mainstream approaches, studios that employ journalistic, historical, or essayistic research to tell nuanced interactive stories — or games that I’ve come to label essay games — use choice as a narrative device. In essay games, choice serves as moments of introspection or critical self-reflection. Instead of using choice to leverage a player’s sense of agency in shaping the game world, these historical and research-based games focus on how a player chooses to witness and reflect on the world they’re inhabiting.

Action-oriented player dialog options as Commander Shepard in Mass

Effect

Action-oriented player dialog options as Commander Shepard in Mass

EffectTwo excellent examples of this approach are 1979 Revolution: Black Friday by iNK Stories and Attentat 1942 by Charles Games. Not only refreshingly distinct in narrative and visual design, these two essay games attempt to reconfigure how choice rewires agency by making it clear that your actions won’t affect the overall outcome of the events you’re playing through. Without that common incentive, the audience instead must evaluate their choices on entirely different criteria, whether that be to create emotional connection, to discover something new, or to reconsider a historical event. That is, player choice becomes less consequential and more expressive.

In order to understand this design shift, it’s important to consider how narrative choice has been designed and implemented in AAA games beyond the above Mass Effect example. Though narrative choice has long been an important feature for studios invested in immersive storytelling, the growing popularity of choice-driven mechanics across the games industry can be attributed in large part to developers like Bethesda, BioWare, and Telltale Games. These studios often use choice as a design mechanic, prioritizing the way in which narrative doesn’t merely tell a story but acts as a quantifiable metric to enhance other character stats or traits (morality, XP, NPC alliances, charisma, in-game resources, etc.). In the Fallout franchise, when you choose narrative actions that further the central plot or advance a side quest, you’re rewarded with experience points. As a result, the narrative elements become subservient to leveling up your character.

For AAA developers, pairing choice with gameplay mechanics is an efficient way of making players feel like their actions have consequence. Molly Maloney, a narrative designer who worked at Telltale, highlights this approach as a practical concept in a talk at the Konsoll conference in 2017. When planning out her designs, Maloney starts with the question, “What can the player change?” These moments, according to Maloney, help shape emotional response from the player, and in turn create dynamic ways for designers to write narratives with personal stakes. To Maloney, engagement in video games should encourage players to make tough choices whenever possible because those choices in turn force the player deeper into the designed world. This argument is compelling for a lot of narrative designers, and often leads to exceptionally rewarding feedback from players wanting to feel like their actions immediately shape their experience.

The implementation of this design tactic unfortunately results in didactic explanations to the player that their actions have shaped the game world. This is often communicated via purely mechanical terms. Whether the player gains experience points, or raises the bounty on their head, or is shown that they’ve only completed 42% of the possible outcomes, the emotional responses that Maloney aspires for are reinforced only by game-mechanics.

I’d argue that succoring storytelling to mechanical operations paradoxically softens the impact of narrative by inherently making the interaction feel more like passing a skill-check than an actual conversation. Agency, under this design strategy, is only achieved by turning narrative into a calculable action. Though this affords designers an opportunity to create experiences with maximal replay value, it turns our most basic form of communication into a computational formality.

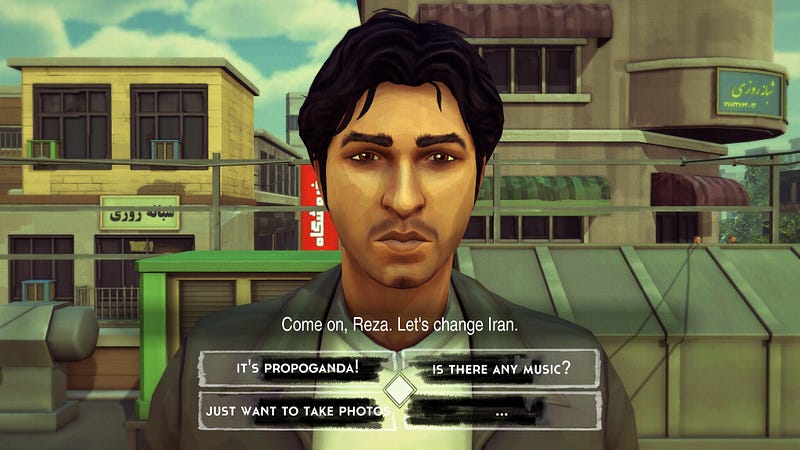

In

1979 Revolution: Black Friday, the playable character Reza Shirazi is a young

photographer

In

1979 Revolution: Black Friday, the playable character Reza Shirazi is a young

photographerWhen we consider how 1979 Revolution: Black Friday by iNK Stories employs choices and branching narrative we can immediately see how the narrative direction of this game isn’t focused on agency as much as it’s interested in exploring the multifaceted politics of the Iranian Revolution of 1979. The central protagonist, Reza Shirazi, is being interrogated after the theocratic revolution has succeeded in overthrowing Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi and Ayatollah Khomeini has taken power. Situating the player in this position of simulated compromise, vulnerability, and uncertainty makes the subsequent branching narrative choices loaded with strife and significance. Those choices, which primarily occur in flashback sequences based on real-life events supported by well-documented research, are written and executed in such a way that ask the player to reflect on their own personal, real-world political beliefs and biases.

As you interact with various political and social factions that comprised the coalition of leftist, Marxist, and Islamist revolutionaries, the narrative choices are just as much about storytelling as they are about reflecting a complex history too often simplified by Western media. As a result, the game’s choices not only educate the player but also probe complicated political debates about civic duty and an individual’s role within a society of unrest. The game presents a character struggling to know where they stand after the dust settles and, as a result, the player’s agency is framed with the knowledge that their actions won’t change the real-world outcomes of the revolution but rather shape their own personal stance on its nuanced politics.

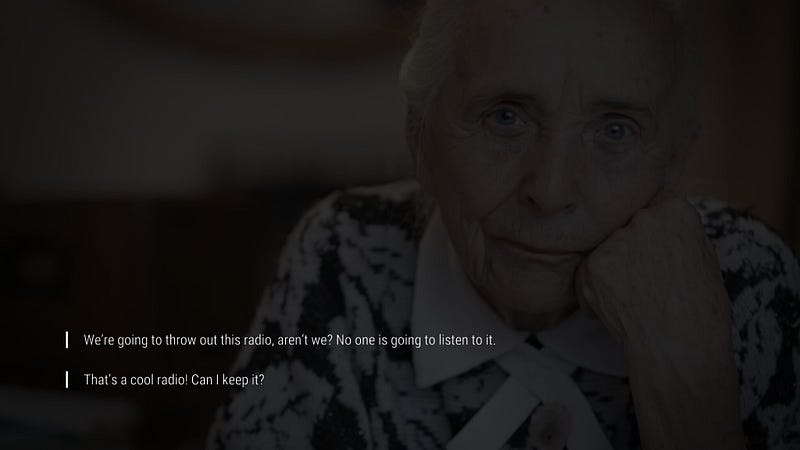

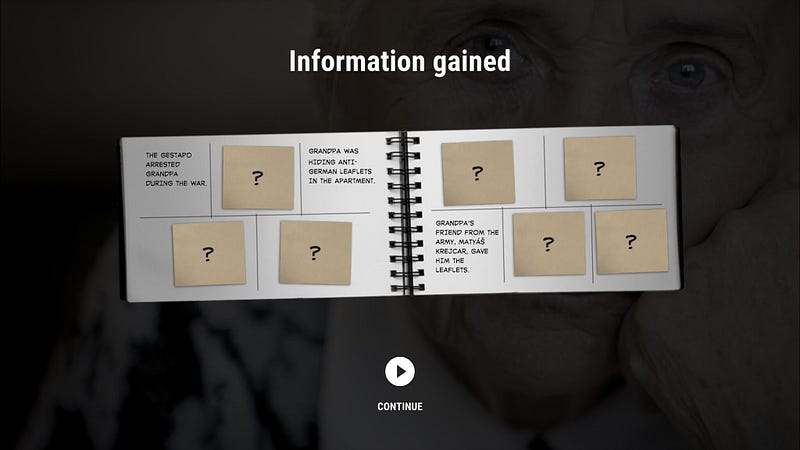

Two dialog

options in Attentat 1942

Two dialog

options in Attentat 1942Where narrative choice in 1979 asks players to reflect on ideological motivations by directly engaging with historical events, Charles Games’ Attentat 1942 explores another set of historical events through reliving old memories. Designed as an interactive video documentary and animated graphic novel, Attentat 1942 uses dialog options and choice in order to explore the central protagonist’s personal relationship with his grandparents and their attempt to survive the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the Nazi Germany. Choices manifest in this game by cycling between conversations with your relatives and reliving some of the memories sparked by helping your relatives pack and relocate their home. Shifting between the past and the present highlights the way the protagonist’s relationship with their family changes the more they learn about their past struggles.

That process of discovery not only flavors different text options, it also forces the player to pause and reflect about how they want to “replay” moments from their grandparent’s past. Choice becomes less about affecting their plight and more about bridging the horrors of the past with the uncertainty of the present. More than a mere educational exercise in “remembering our heritage,” Attentat 1942 tells a nuanced story of how seemingly ordinary people live through extraordinary circumstances and carry the weight of history for their entire lives. Ondrej Trhon from Charles Games described how their design process prioritizes player introspection:

“We offer different standpoints you can explore via gameplay (asking the right questions, etc.) […] Characters have different feelings about events that happened, about particular injustices and grudges. Via dialogues you are confronted and made to reflect on different ways ordinary people experience history. And since it’s an adventure and it is you who is asking questions, there’s a much more sense of hands-on experience, and we ultimately hope this creates space for empathy.”

Trhon attributes Charles Games’ methodology to a fundamental desire to tell stories that not only create a sense of understanding but also ask the player to consider a range of emotional responses to historical events. Early in the design process, Trhon admits that collaborations with screenwriters fell apart after the design team felt the script was “too bombastic,” presenting an artificial and narrow perspective on the horrors of Nazi occupation. By widening the lens around the historical events and allowing players to personally navigate that history for themselves, Charles Games avoids making the occupation and War about an individual figure shaping history but how people worked to support one another, fight for liberation, and share their burdens. The choices in Attentat 1942 make those varied perspectives of these events clear and guide the player to consider how the typical narratives we share and know about these significant moments in history need continued reflection and examination.

This point is perhaps the most salient strategy found within the narrative designs of essay games. For nonfiction stories to acknowledge that history is an ongoing, collaborative, and research-intensive process that requires input from many different perspectives, designers must abandon the restrictive nature of choice as purely a mechanical means to an end. Instead of promoting simplistic causal immersive experiences, the most agentive thing that games can provide players is the realization that our contemporary reflections on the past can also shape our present.

This approach for creating powerful, meaningful, and thought-provoking experiences isn’t limited to only telling historical stories. Essay games’ methodologies can also be applied to telling personal stories from underrepresented voices, to speculating about our imminent future based on current political and cultural trajectories, or to satirize oppressive narratives that AAA games all too often reinforce. Artists and studios wanting to truly invest in the difficult but necessary work of examining our relationships to each other must champion how choice and player agency help us not only reflect on the decisive events that continue to shape society, but how we can strive toward a better future.

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.