Beyond Tweets and Streets: Standing up to Hate

An Immerse response

“Solidarity is a commitment, not a gesture.”

Many thanks to Doug Bierend for this stellar analysis about the power and potential of digital platforms in organizing social movements. His perspective was powerfully reaffirmed the day after Trump’s inauguration. The Women’s March that drew millions across the country and around the world was started by a Facebook post. Since then, thousands have been drawn to streets and airports to support immigrants who have been targeted by Trump’s executive orders.

Digital platforms are especially useful at connecting the convinced. The question of how to move messaging and engagement beyond a self-selecting audience deserves a longer analysis, and perhaps Bierend or one of the analysts he links to in the article will take on this tough question.

Using examples from the anti-hate movement, I want to echo Bierend’s message that if we want to make real change, we have to do more than engage online. He captures this message so clearly here:

Digital platforms have proven instrumental in sparking movements that spill into the streets. But in these cases the role of technology tends to recede as the ephemeral, emergent, fast-twitch connections give way to the grinding mechanics of analog organizing.

As Bierend reminds us of the “grinding mechanics of analog organizing” he points out how vital it is to build connections with people outside the screen and that standing with people and making change is a significant commitment that can’t be achieved by tweets alone.

Easy as it is to confuse new forms of media as revolutionary messages unto themselves, movements live or die on what happens outside of the screen. Solidarity is a commitment, not a gesture.

Cases in point

Standing up to hate requires a long term commitment. For over twenty years, Not In Our Town—a movement that was sparked by a PBS film we produced—has been learning about how to successfully respond to hate and intolerance from communities on the ground. Social media has greatly advanced the ability to spread awareness and mobilize people. But, real and lasting change that can be felt by people who are targets of hate, in the places they live, requires more. Digital engagement is empowering if it is followed by person-to-person contact, brainstorming, and a persistent commitment to change the atmosphere that can lead to hate crimes.

Here are a few examples:

Image source:

WTOL

Image source:

WTOL

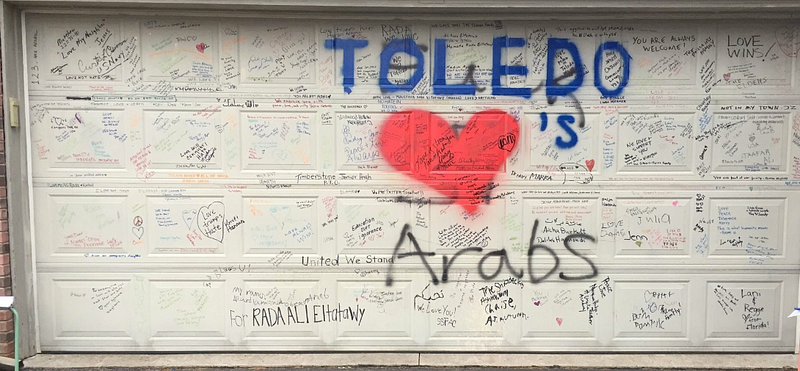

Racist expletives were recently painted on the home of an Arab American family outside of Toledo, Ohio. Many of us learned about the attack on social media, and virtual signs of support swelled online. But what probably mattered most to this family was the action of their neighbors. Shortly after the attack was documented and reported, neighbors showed up and painted a heart over the hateful graffiti.

Real humans bought the paint, went to a house where people had been harmed and tried to make them feel safe again. For hate crime victims, neighbors really matter. Local residents who are ready to stand with you if your family is being targeted can not only make a family feel secure, strong clear actions of support for victims of hate can be a deterrent to the next attack. This is especially true when people acknowledge the dangers of hate and make a deeper commitment to do something to stop it.

Another powerful example is the “I’ll walk with you” campaign after the hate crime killings of an imam and his friend in Brooklyn in 2016. Thousands of New Yorkers signed up to walk with their Muslim neighbors to and from public transportation so they could feel safer from hate and bias attacks. The real life interactions between the people who connected are the launch pad for long term and deeper understanding. How do we take those moments into our day to day lives?

A hate attack can lead to deeper connections between people in a community, and an exploration of the day-to-day intolerance that too often lives under the surface.

The arson attack on a Black family’s home in the middle of the night was a wakeup call for the relatively serene coastal town of Manhattan Beach in 2015. Ron and Malissia Clinton, and their three children were one of the few Black families in the neighborhood. Absent another motive, they and many others in the community assumed that the attack was a hate crime. Malissia Clinton shared a message online with her Manhattan Beach book group that she and her husband were thinking of moving away.

Her friends mobilized quickly with a Facebook call urging Manhattan Beach neighbors to attend a vigil in support of the family. Tech leader Peter Tam launched a GoFundMe campaign urging people to contribute to a reward fund to help find the perpetrator. Three days after the attack, hundreds of people gathered near City Hall for a vigil to express their support for the Clintons and the community’s firm stand against hate. “I have no fear, because I have you,” Malissia Clinton told the crowd.

Digital organizing made the response to a hate attack successful, but what happened next will have an even deeper impact. A year after the arson attack, law enforcement still had no leads on who had set the Clinton’s house on fire. In the meantime, the incident sparked new conversations about racism and intolerance. Malissia began talking to other Black parents and learned that their children were being bullied. Working with Manhattan Beach Education Foundation, the Clintons suggested that the reward fund, which had swelled to over $30,000, be used to promote social inclusion in the schools. Not In Our Town produced a short film about what happened to the Clinton’s, and Malissia invited key leaders from the community to her home to watch the film. City council members, the school superintendent, school principals, PTA leaders, teachers and community activists held an emotional discussion after the screening, and learned that it wasn’t just this incident of hate they needed to address. Parents of students of color opened up about the persistent bullying that young people were facing at school and in the community.

The convening became a moment to open a discussion about racism and intolerance that had not been taking place. The group made a commitment to launch a campaign to spread the story and take on the difficult work of addressing bullying and hate. At a follow up meeting of even more participants, the group created a Social Inclusion group affiliated with Not In Our Town and launched plans for ongoing events.

We have to be there for each other in the days ahead. Social media will spark and connect us. But it is our day-to-day commitment to reach out beyond our comfort zones and to do the “grinding work of analog organizing” that will lead us to the big changes we need to repair the world.

Patrice O’Neill is a documentary filmmaker and the founder and executive producer of Not In Our Town, a movement to stop hate and build safe, inclusive communities for all.

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.