Part 6 in a series by Kamal Sinclair

Most of the concerns about equality in emerging media that interviewees raised in this research project relate to mitigating our blindspots. But their “boundary issue” concerns are more focused on mitigating our vulnerability to bad actors — people and entities that seek to exploit the disruption of new media and emerging technology for unethical or illegal objectives.

We are living in a time when anonymity simply does not exist. Historically, people could move through the world with relative privacy, but that is not possible now. Satellites know your movements, your economic activity is constantly tracked and archived, wearable devices can know your thoughts, films you watch can also watch and capture you, and cameras know your face — even if you’ve never participated in social media. As a disturbing art project by Heather Dewey-Hagborg demonstrates, you even shed DNA everywhere you stand, sit, or walk.

Some say, “If you have nothing to hide, there is nothing to worry about, right?” If we look to the future dystopia narratives such as Minority Report or Black Mirror, we begin to see cracks in this argument. Interviewees for the Making a New Reality research identified the lack of boundaries that comes with the advent of new technology as especially problematic when you consider America’s history of inequity, and systemic oppression or exclusion.

For example, many of the African-American interviewees referenced the constant sophistication of systems of oppression that affect their lives and communities as a source of their anxiety about this next phase of media disruption. “What might be used against us that we don’t even see coming?”

A history of surveillance and discrimination

I can personally relate to these fears. As a child of the Civil Rights generation and a member of the Hip Hop generation, I experienced a traumatizing shift in tactics of oppression of my community from the 1980s to now.

My parents and grandparents were very active in the work of racial unity and equality, starting in the 1950s. For example, my white grandmother help to start the NAACP in Maine and was a community organizer until the day she died. My black father did a Freedom Ride to the South in the 1960s that almost took his life. He was chased by the Ku Klux Klan out to the swamps, where he had to hide in a shack for three days without food. However, by the time I came along many of the civil rights movement’s goals had been presumably achieved. This created a belief that although there were still obstacles to overcome, the path was relatively clear for our generation to reap the benefits of the equality and equity our parents fought to win — the Brown v. Board of Education, Civil Rights Act, and the Voting Rights Act (Still working on the Equal Rights Amendment.)

David Lemeuix in Question Bridge: Black Males, explaining the

disconnect between the Civil Rights and Hip Hop Generation at the dawn of mass incarceration.

David Lemeuix in Question Bridge: Black Males, explaining the

disconnect between the Civil Rights and Hip Hop Generation at the dawn of mass incarceration.

Despite the negative stereotypes that commercial media would have us believe, the Hip Hop Generation’s music and culture called for the continuation of our parents’ work by being proud of our heritage and fighting the powers of oppression. The movement crossed over from music to every aspect of art, media, lifestyle and culture. Public Enemy, Arrested Development, Spike Lee films, KRS-One, Mary J Blige, X-Clan, Sister Souljah, The Roots, Erykah Badu, Tribe Called Quest, De La Sol, The Fugees, Rennie Harris, Mos Def, Saul Williams, Queen Latifah, Dead Prez, Digable Planets and Common were just a few of the cultural leaders that steeped us in messages of our nobility and called us to advance the community. Unfortunately, we didn’t understand the power we needed to “fight” had morphed significantly from the explicit Jim Crow segregation laws, police dogs, and burning crosses that our parents faced. We were like frogs boiling in a pot of water that didn’t understand the dynamics of The New Jim Crow that were killing and imprisoning us at unprecedented rates.

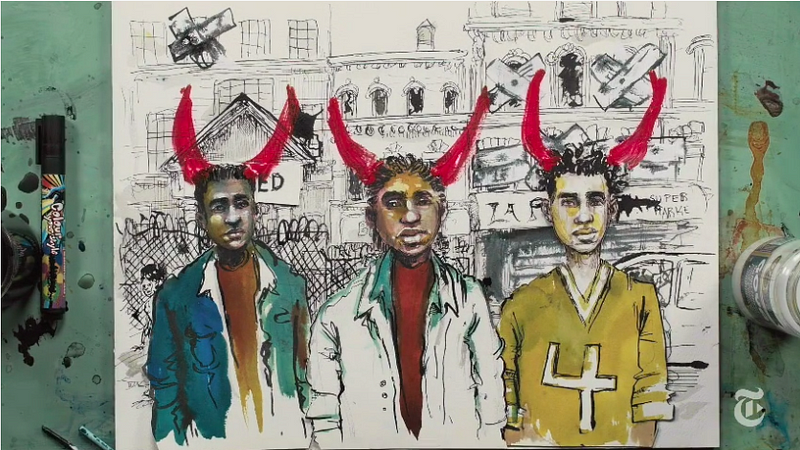

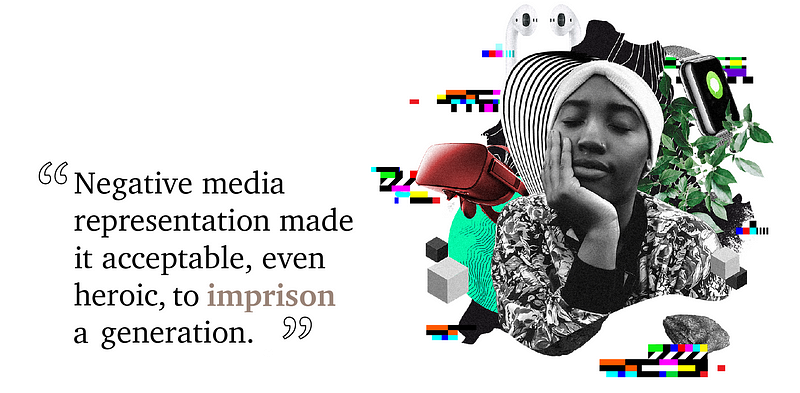

Even more disturbing was how the curation of negative images and narratives about Hip Hop had been so effective in drowning out the positive aspects of the culture, biasing consumers of mass media globally to think of it as criminal. This dehumanization and disempowerment even caused rifts to appear between the Civil Rights and Hip Hop generations, which deeply impacted our resilience in the face of this new type of oppression. The negative media representation made it acceptable, even heroic, to imprison a generation of black and brown people, deeply disrupting kinship systems, economic mobility, and the political power needed to fulfill “the dream.”

Jay

Z: “The War on Drugs Is an Epic Fail,” New

York Times

Jay

Z: “The War on Drugs Is an Epic Fail,” New

York TimesNow, members of the black community wonder, how much harder will it be to protect our children from bad actors or systemic oppression in the future state of these emerging technologies and media? What other ways will our societies be affected by the boundary issues of emerging media? These are some of the urgent questions and concerns raised by the interviewees of the Making a New Reality research. They have rightly identified emerging technology and media as the latest front of the modern-day civil rights movement.

Boundary issues up close and personal

“Is this just paranoia?” I’ve wondered that myself at times. Indulge me, as I explain one way I wrestled with this question in my own life.

I lived through the Blood and Crip wars of the 1980s and early ’90s, the LA Riots, and the ramp-up of mass incarceration. Although my father grew up in Watts in the 1940s and ’50s, where there were drugs and hustlers, I (a goody goody A student from Altadena) had more guns pulled on me and heard more gun shots than he ever experienced, as guns and drugs flooded into black and Latino communities.

Imperial Dreams by Malik Vittal —

illustrates systemic traps in black and brown communities.

Imperial Dreams by Malik Vittal —

illustrates systemic traps in black and brown communities.When I “got out,” I swore I would never put my children through the trauma of growing up in a war-zone like that. However, in 2013, LA’s affordable housing crisis caused me to consider moving back. I was desperately looking for an affordable place in a good school district and failing. A friend said, “You may need to face the fact that you can’t afford to live anywhere but the ghetto. It could be good for your kids. They need to get a little more street smart and be around more black folks.” All of a sudden the trauma of my childhood boiled in my blood and a feeling of rage raised up in me. How dare he tell me to put my children in harm’s way! Then a wave of guilt washed over me, “Am I a sell out? Am I over-reacting? Am I just being paranoid?”

In the end, I decided to take on a second job, move to a smaller (more expensive) apartment in a good school district in a racially, economically and religiously mixed community. Although having two jobs and three kids as a single mother took a major toll on my health, my kids were safe from the dynamics of “the ghetto” — poor education, fear of violence, unjust policing — and the mental health issues that comes from socioeconomic oppression. Still, I always had this nagging voice in my head: “Are you a sell-out? Will your kids know who they are, not being in a predominantly black community?”

Matthew Mitchel at Georgetown University Law

Center

Matthew Mitchel at Georgetown University Law

CenterThen I attended Matthew Mitchell’s workshop at EYEO Festival in 2016 about the over-policing and over-surveillance in black and brown communities and those questions were answered. Mitchell exposed a rigorous and often times illegal network of emerging technologies used to surveil black and brown people in concert with deeply unjust practices (such as stop-and-frisk, summons quotas, and gang injunction laws) that fuel mass incarceration, disruption of kinship systems, and socioeconomic oppression.

My heart sunk to see it all laid out so clearly. I thought about all of the people I’ve known to get trapped by this system, but I also felt a rush of validation: “I’m not a sell-out or paranoid — I dodged a bullet.” My children would have been placed in the middle of a maze of invisible traps if I moved to the “ghetto.” And, unlike me, who had two parents to help me navigate the neighborhood, my children would be more vulnerable to these invisible traps with only one working parent. And, unlike me, they would be faced with systematized racism that is exponentially more efficient via the power of emerging technology.

To be clear, I am very aware of the privilege I have in even being able to make the choices I made for my children. I am also aware of the deficits my children will have in not being in a community with more opportunities for affinity, because of the traps fueling issues like the schools to prison pipeline. Finally, I’m deeply humbled by the parents (single and partnered) doing the amazing job of raising children with dignity, purpose and nobility in the midst of neighborhoods targeted by structural oppression and helping them navigate through the maze (like my own parents did for me and my four siblings). However, I believe firmly that these resilient and phenomenal parents should never have to worry about their child getting abducted by the police for alleged petty crimes and placed into an adult penitentiary for years before they are tried in a court of law, with much of the time in solitary confinement. That is unacceptable. We can not allow new technologies and media practices to worsen this dynamic.

This article takes just one look at a very complex and broad set of boundary issues through the narrow lens of a few ways my community is, or could be, affected. Please check out the supplemental articles to learn other ways interviewees are seeing social justice challenged by emerging media and technology’s lack of boundaries. Not only do interviewees discuss their concerns about Security, Privacy and Regulation of emerging tech, but they also share concerns about the Lack of Ethical Design Practices the Lack of Safe Spaces, and issues related to being Minorities in Majority Spaces. These are critical insights that help shed light on possible intervention strategies to set a positive direction in our process of making a new reality.

The Making a New Reality research project is authored by Kamal Sinclair with support from the Ford Foundation JustFilms program and supplemental support from the Sundance Institute. Learn more about the goals and methods of this research, who produced it, and the interviewees whose insights inform the analysis.

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.