Building Irreverent and Intersectional Products for Women

Design justice and co-creation in the “Make the Breast Pump Not Suck” Hackathon

“The future of breastfeeding is irreverent and intersectional, with mamas, parents, and babies at the center.” This forward-looking values statement from the “Make the Breast Pump Not Suck” project team can be found in Speaking Our Truths, a book filled with firsthand accounts of what it’s like to breastfeed in the US today. While the project team is working to make that vision of the future a reality, there are many hurdles to overcome.

Perhaps nothing encapsulates the present-day struggles better than the design of the typical breast pump itself.

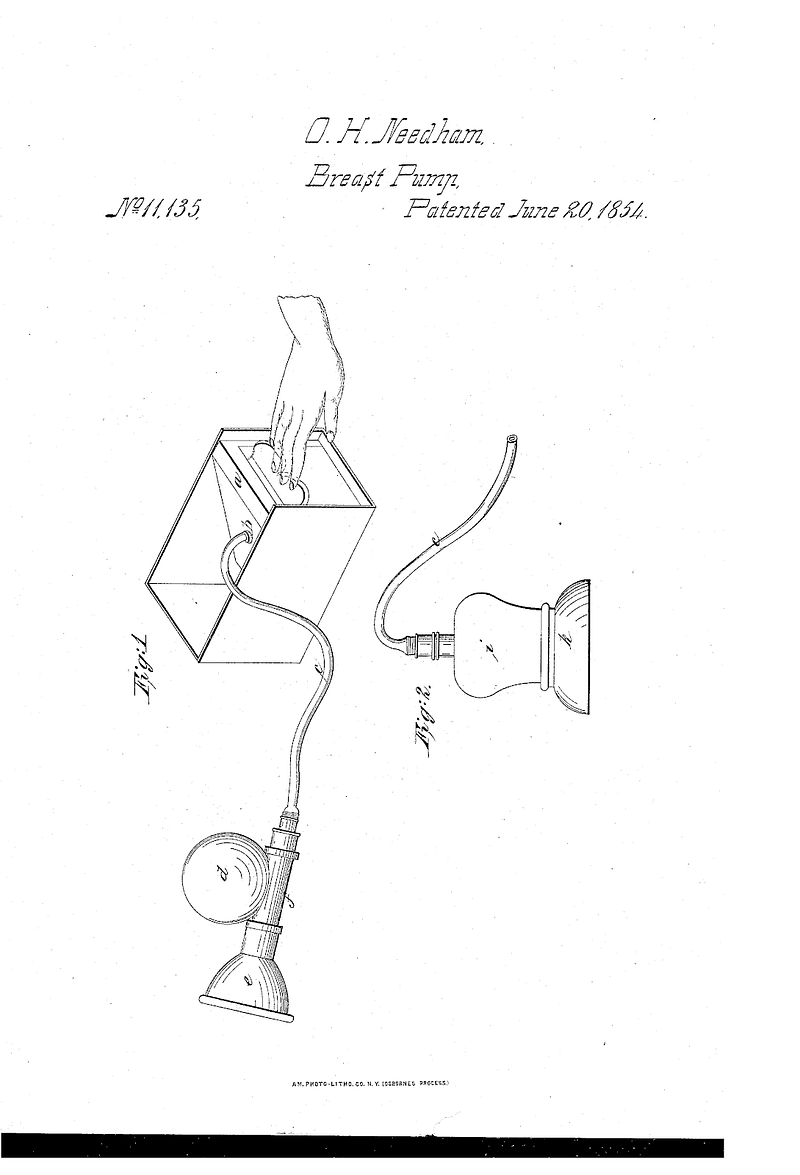

Illustration from Patent №11135

for a breast pump, patented June 20, 1854

Illustration from Patent №11135

for a breast pump, patented June 20, 1854Noisy, clunky, and with many hard-to-clean parts, the breast pump is a piece of technology that has long been in need of innovation. In the “Make the Breast Pump Not Suck” team’s research, breast pump users identified mobility, discretion, easy cleaning, and comfort as key areas for improvement.

Systemic issues such as cultural taboos and hostile work environments only exacerbate the problems that those using breast pumps face. Further, policy issues surrounding the broader context of breastfeeding, such as a lack of federal paid parental leave policies, point to the ways that the breast pump’s issues are connected to broader issues in maternal and reproductive health. It’s within this context that this project began.

Alexis Hope, a current graduate student in the MIT Media Lab, and Catherine D’Ignazio, currently an Assistant Professor in MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning, started the project in 2014. They expanded their team in 2018 to include Binta Beard (Policy Summit Lead), Kate Krontiris (Research Lead), Rebecca Michelson (Project Manager), and Jennifer Roberts (Equity and Inclusion Lead). Hope explained that the impetus for the event came from D’Ignazio’s own experience navigating structural barriers to breastfeeding while working at MIT. The creators of the “Make the Breast Pump Not Suck” hackathon do not describe their approach in terms of a specific design framework. However, frameworks such as participatory design and design justice provide useful lenses to use in drawing lessons from the project’s successes.

A gallery wall from the “Make the

Breast Pump Not Suck” Hackathon in 2018. Photo Credit: Ken Richardson.

A gallery wall from the “Make the

Breast Pump Not Suck” Hackathon in 2018. Photo Credit: Ken Richardson.In Collective Wisdom, we provide a survey of participatory frameworks used across a wide array of fields, including participatory design, which is characterized by a deeply collaborative process between trained designers and the intended users of a particular system. Although it has political roots, present-day conceptions of the practice vary widely. As such, the term “participatory design” can be found as an approach in corporate design processes, as well as an underlying philosophical approach to design work overall. This has fueled the development of design frameworks that more explicitly address issues of inequity through participatory methods. Design justice is one such framework, with a set of guiding principles that prioritize design’s impact on communities over the intentions of designers.

Hope says that work by the Design Justice Network informed their project’s shifting approach. This is perhaps most evident in the hackathon’s statement of values, which forefronts inclusivity, intersectionality, and equity. The commitment to these values has led to a more comprehensive form of partnership over time. Hope says of the group’s approach to creating an event through participatory approaches, “I fundamentally believe in the relationship-based approach… slowing down your process quite a lot.” This attitude is reflected in the evolution of the project from more typical participatory design methods in 2014 to the longer, more deeply collaborative approach taken in 2018.

The original Make the Breast Pump Not Suck Hackathon in 2014 gave general audiences a chance to submit ideas, stories, and prompts that formed an idea wall that hackathon teams referred to for inspiration. It also included scholarships to amplify under-represented voices in hackathon teams. This event’s noteworthy outcomes include product launches and media attention for breast-feeding issues. However, the 2014 hackathon’s audience, according to the team, was a largely privileged group. It did not include as diverse a range of participants as the team had hoped. Further, most project teams focused on the technical and mechanical aspects of existing breast pumps, despite the encouragement throughout the event to think beyond technical solutions.

The hackathon’s second iteration in 2018 presented a significantly more intersectional focus and more deeply collaborative process of event planning. The build-up to the event included a community innovation program that supported groups already working on issues of reproductive justice across the country. These groups provided monthly input on the event planning and worked on projects during the hackathon event.

A scene from the 2018

hackathon.

A scene from the 2018

hackathon.This deeply collaborative approach had some key benefits for the hackathon planning team overall. It expanded their conception of community needs and opportunities, as well as problem spaces for hackathon projects. Hope explained that this collaborative event also resulted in designs that would not have come out of the 2014 hackathon. For example, Rachel Lorenzo, founder of Indigenous Women Rising, worked with her team on breastfeeding-friendly prototypes of traditional clothing.

When asked about practical advice she might give people planning similar events of their own, Hope notes that everything takes longer than designers intend. There is a need to budget time and resources that are not usually accounted for in the planning process, as relationship building cannot be rushed. She also suggests that White folks working in spaces of equity invest time and resources to unpack the damaging effect that structural racism can have on a participatory project like this.

Currently, D’Ignazio and Hope are taking the lessons they learned from these events and are applying them to the topic of menstruation in a hackathon event slated for 2020 titled, “There Will Be Blood.” Of all the lessons learned throughout the “Make the Breast Pump Not Suck” events, Hope highlights one in particular. “My main takeaway is this type of work is never really finished,” she says of the partnership-building aspects of the project. There are always more ways to improve and learn in a collaborative process, and there are always more ways to advance justice in professional/academic fields.

This article is part of Collective Wisdom, an Immerse series created in collaboration with Co-Creation Studio at MIT Open Documentary Lab. Immerse’s series features excerpts from MIT Open Documentary Lab’s larger field study — Collective Wisdom: Co-Creating Media within Communities, across Disciplines and with Algorithms — as well as bonus interviews and exclusive content.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.