How do we continue to grow distribution and exhibition of virtual reality?

Working in the VR industry, I have become very used to living between perpetual hope and despair. The good news is that best practices for exhibition and distribution are emerging and there really is a there there—or the shape of a “there” emerging at any rate.

I’ve just returned from New York, where I program Storyscapes at Tribeca Immersive, part of the Tribeca Film Festival. I also run a non-profit in South Africa called Electric South, where my team and I are working on a distribution strategy for VR in Africa. I think about distribution and exhibition all the time, along with bigger ideas around art and value. I also worry about how artists (and facilitators/conveners/producers like me) can pay our bills each month. So, in this article I want to sketch out the ways that film festivals and museums are serving as exhibition spaces, take a look at the rise of Location Based Experiences (LBEs), and suggest some ways that the ecosystem of exhibition and distribution needs to mature to make sure creators can more reliably connect their work to audiences and get paid.

I’m using “distribution” and “exhibition” rather interchangeably but I generally refer to distribution as an umbrella term which includes things like festivals, special exhibitions and online, whether the work is led by a professional distributor or not. The focus here is more on festival and other exhibition spaces like dedicated location-based experiences (LBEs), galleries, museums, art spaces and libraries, and what this means for the VR ecosystem. I welcome any responses to this, especially if anyone is interested in delving deeper into opportunities and challenges around online and in-home VR distribution (which I barely touch on here), particularly given the fact that mobile VR seems to be going away.

What do film festivals do for VR?

Sundance New Frontier and IDFA DocLab have been showing new forms of work since 2007. There was a shift in 2012 when Nonny de la Peña showed Hunger in LA at New Frontier and audiences got a hint of the second wave of virtual reality that was soon to follow. Since 2014, many established film festivals have started showing VR and dedicated VR festivals have sprung up around the world.

There are real challenges to showing VR work in a festival environment. Space is often very limited. There is a trend towards big installations, often with actors or complicated technical set-ups (moving floors and mo-capped actors were both a feature of Jack at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2018) but the pieces are only up for a week or two, sometimes even less. Audience demand is high and the pieces are getting longer and more involved, meaning that not many people can experience the work in a given period. Adding more headsets is one way to mitigate this, but some of the pieces are specifically designed for only one or two people at a time.

Loren Hammonds, senior programmer for film and immersive at Tribeca Film Festival and my colleague on all things Tribeca Immersive, wants to make sure that there is still a place for big, ambitious projects there. “I find it important to show the large scale work because part of what I want to show as a curator is the new way of telling stories. It’s not easy to do, it’s a huge challenge given space, budgets, and the temporary nature of festivals.”

The projects require docents or staff to take audiences through the experience. This does not just mean cleaning headsets and putting them on people’s heads and starting the experience. Often docents are also part of an extensive intro and outro to the experience that takes place in the headset. Getting good docents can really change the experience for the project creators.

Spheres producer and Crimes of Curiosity founder Jess Engel agrees about the importance of good docents to make a successful experience and to take the pressure off creators who otherwise have to be in the space the whole time running their project or alternatively hiring people — both of which are problematic if you are an independent artist. She also underlined how vital it is for producers to budget for festivals. “There are a lot of costs associated with being at festivals and every festival handles it differently.” She adds that it is really important to put the work first. “Festivals are great for building awareness and getting press. Sometimes creators can get so focused on a festival that they submit work that isn’t necessarily ready yet.”

Myriam Achard of the Phi Centre in Montreal—a multi-disciplinary space dedicated to art in all its forms and one that many of us wish was replicated because of its support for immersive work and beautiful installation design— says that the current VR model at film festivals does not always work. Everyone is chasing premieres and not thinking enough about audience experience. “It’s a mistake if film festivals copy the film world. We need to honor the art.”

IDFA Doc/Lab’s Caspar Sonnen is very aware of the premiere problem. He talks about the challenges around understanding supply and demand in this new world. He doesn’t care so much about what the exact model is for festivals but says we need to be critical of what we are doing on an ongoing basis:

“I would love to just show my personal favorites but we also need premieres. Press wouldn’t write about the work, decision makers wouldn’t be so inclined to see it even if they haven’t seen it at other festivals and general audiences also go for the new stuff. We all have a bit of an obsession with newness and it’s not helpful to just say premieres are bad. But it’s a very serious situation that work is only considered fresh for a short amount of time during which only a small amount of work gets seen. That’s why spaces like Phi Centre are so needed.”

ANAGRAM’s

The Collider, which premiered at IDFA

Doc/Lab and was then shown in Storyscapes at the Tribeca Film Festival

ANAGRAM’s

The Collider, which premiered at IDFA

Doc/Lab and was then shown in Storyscapes at the Tribeca Film FestivalOne of the things festival programmers are thinking about is how to make the whole space feel cohesive and not just like a bunch of VR experience thrown together. As Dan Tucker, curator of Alternate Realities at Sheffield Doc/Fest says, “We’ve always worked really hard on making the space a story as well. We want to keep making a space with a narrative, work that sits alongside each other.”

For some projects, the festival circuit essentially becomes the distribution strategy and all the programmers I spoke to are concerned about this. “The world hasn’t been built yet so we’re in an awkward place,” says New Frontier’s Shari Frilot. “I don’t want festivals to be de facto distribution for VR. Our job is to find new work, discover new voices. Not be a platform for distribution.” Hammonds agrees, “Often the buzz begins and ends with us. This needs to be fixed.”

Tucker was speaking to me from the Barbican in London, where he was touring work after Doc/Fest concluded. “We tour pieces that show at the festival first. This ensures that the work is seen. But this needs to be funded and it’s complicated to get these relationships off the ground. You have to get people to see the value and sometimes artists need to understand why it’s important.”

The rise of location-based experiences (LBEs)

Festival programmers are excited about how location-based experiences (LBEs) are extending the opportunities for work to be seen beyond festivals. This is not just an interesting emerging space for festival programmers, it also goes some way to make up for the poor sales of VR headsets, the domination of games in online distribution and the fact that much of this work is just not being seen in the home. As Peter Rubin pointed out in Wired, “It’s not that people don’t want to use VR — it’s that doing it at home is still the province of early adopters.”

“We’ll never been able to meet demand in terms of audience access,” says Frilot, “Adding VR cinemas only helps a little bit. But festivals are only the beginning chapter. LBE’s are growing. What role can festivals play in building the world beyond festivals? The energy around this world is growing. What strategic partnerships are possible. Could we help LBEs get off the ground? What digital initiatives outside of our festival could we get involved with?”

Frilot emphasizes the role of strategic partnerships in this, “We did this with Lynette Wallworth, we showed Coral: Rekindling Venus at Sundance in a dome and then collaborated with planetariums around the country to show the work. Planetariums are the original dome projections, so it made perfect sense.”

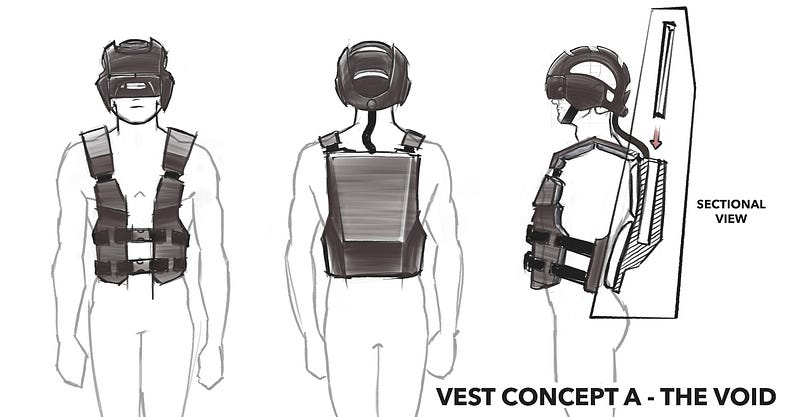

The Void and Dreamscape are examples of big-budget location-based experiences, but independent artists are also taking advantage of the market in LBEs to think about other kinds of venues to show their work. For example, Future of Storytelling ran a pop-up Story Arcade earlier this year in NYC which included Chained: A Victorian Nightmare.

The Void

concept for an untethered VR system

The Void

concept for an untethered VR systemPeople working in the VR world are also looking at what Meow Wolf and Two Bit Circus are doing in terms of creating unique experiences for audiences. There are some less optimistic signs like IMAX shutting down its virtual arcade business, and many smaller arcades closing almost as soon as they have opened. Not everyone is thrilled that there is so much focus on out-of-home and LBEs. Take for example this comment from a blog post on VR distribution:

“The VR industry pivoted in 2017–2018 to talk about how “Out-Of-Home (OOH)” and “Location-Based Entertainment (LBE)” were the real killer app for VR. This is an important industry, seeing the returns of arcades in parallel to the rise of professional videogaming, but calling it the true market for VR is a cop-out. Where is my Atari 2600 or NES? Where is my Alexa or Phillips Hue? I want my MTV.”

Other venue opportunities for VR

Catherine Allen and her team at Limina Immersive have taken a great deal of care to think about what a VR cinema experience should be like, beyond just plonking people in headsets. I recommend reading Verity McIntosh’s very thoughtful talk on VR exhibition environments for more on how the way we set up VR experiences can be welcoming or off-putting to audiences:

“Anxieties include: Am I being watched, photographed, or filmed. Where is my bag, coat, stuff? Is anyone looking after it? Will this headset even work with the hair that I have or the headscarf that I am wearing? Will I get tangled in the wire? Will I fall over? Will someone jump out at me, or touch me in some way? What if I accidentally touch or bump into someone myself? Will it work with my hearing aid, my glasses, my wheelchair? Will this create a sense of sensory overload? What if I feel sick? What if I need to go to the bathroom? Is this a game? Will I be expected to interact or participate in some way? Is this hygienic? Is the kit being cleaned between participants. What if the last person to do this was sweaty—oh no, what if I get all sweaty? Or cry? Or my make-up rubs off on the headset?”

Limina’s dedicated VR arts space is also housed in a larger cultural institution, Watershed, which is a smart move in terms of attracting audiences and being part of a larger cultural conversation.

Museums are also taking on VR exhibition. This is exciting because there is so much innovation happening in the museum space now. (I recommend following MuseumNext on Twitter if you are interested in this area.) Like Limina operating within the space of Watershed, it can make a lot of sense to partner with a legacy institution with a built-in audience. There is also the vital issue of access. Many museums are working very hard to think about who their visitors currently are and how to be more accessible and community-focused. Libraries are also a very exciting space to think about in terms of democracy of access. Electric South ran two VR exhibitions in the Central Library in Cape Town in 2016 and 2017, and they were packed — with a far more diverse audience than you would see in many spaces here in Cape Town (which has a bit of a problem in this regard, to put it mildly).

Laurie

Anderson’s Chalk Room at MassMOCA

Laurie

Anderson’s Chalk Room at MassMOCALessons from the art world

When you look beyond the film festival circuit there is also a whole world of digital, art & music festivals where VR work can be seen: Abandon Normal Devices, STRP, Playgrounds (the Netherlands are very good at this it seems), Ars Electronica, Resonate, Brighton Digital Festival, Mutek, Sonar+D, and Nuit Blanche, which takes place in many cities including Brussels. This is just to name a few.

There is definitely some buzz happening around VR in the art world in particular. Phi is showing two art pieces in Venice: Renata Morales’ Invasor and Marina Abramović’s Rising. New company Tin Drum created The Life by Marina Abramović that recently showed at the Serpentine in London. Daniel Birnbaum left his job at Moderna Musee in Stockholm last year to become director of VR company Acute Art.

Mary

Sibande’s A Crescendo of Ecstasy, produced by Eden Labs

Mary

Sibande’s A Crescendo of Ecstasy, produced by Eden Labs The Lost

Botanist by Eden Labs & Tulips and Chimneys

The Lost

Botanist by Eden Labs & Tulips and ChimneysAnn Roberts is commissioning some extraordinary South African VR work at TMRW Gallery in Johannesburg. The artists work mostly in Tiltbrush, which Roberts says becomes just another brush, another tool for them. Roberts is very interested in all the things that surround the VR experience, projecting what the person is seeing or “creating a sculptural object that the VR sits in. This helps the audience to engage with the work and not get blocked by the tech and is also a potential collectible.” Eden Labs in Johannesburg, which have worked on many of the TMRW Gallery exhibitions, are creating some of the most beautiful custom built headsets for VR I have seen, including a Mary Sibande piece for TMRW and a new animated project called The Lost Botanist that is premiering at Annecy.

Marshmallow Laser Feast’s (MLF) We Live in an Ocean of Air has just finished a very successful run at the Saatchi Gallery in London. Producer Nell Whitley and the MLF team have been very astute about coming up with a robust business plan for the work they create. They tend to only do one or two film festivals, as it is not cost effective for them to tour the festival circuit—but this does not mean the work does not tour or get seen. Another MLF project In The Eyes of the Animal has toured all over the world in various venues. Nell makes the point that VR isn’t the only space to have capacity issues and she uses other models as inspiration when she works on her plans. “Do the calculations. Think about how theme parks have solved these issues.”

She thinks deeply about things like the duration of the piece and the whole experience, including getting people in and out—and the costs to operate, taking into account tech redundancy (extra headsets and other gear to provide cushion for malfunctioning). The MLF team worked this out and We Live in an Ocean of Air was extended twice at Saatchi. Based on a revenue share model with the gallery, the show will end up in the black for the exhibition. The success for the piece as a whole will be proven if MLF manage to successfully tour the work.This is all good news for the rest of us who are thinking about running these kinds of exhibitions — but it takes a huge amount of planning and work.

What could a robust VR ecosystem look like?

To state the obvious, we need a robust ecosystem where work is being both funded and distributed. Arnaud Colinart—one of the creators of Notes On Blindness: Into Darkness and now with prolific VR production studio Atlas V—has said that “because VR headsets come out of Silicon Valley culture people wanted a blockbuster on day one.”

This didn’t happen, and there has never been much patience about this fact. The role of the tech companies in this ecosystem is something that often feels a bit feast-or-famine — with many passionate people who are working incredibly hard to support creators but are also ultimately employees in a large system that’s not dedicated to supporting art and storytelling, and where they do not have a huge amount of say in long-term planning.

Beyond tech, funding and financing are needed to support the ecosystem for sure—but across the board so that all the dots are connected from workshops and training, to production, to distribution and audience building.

It is wonderful to see innovation in the US public media space led by Opeyemi Olukemi with POV Spark. New Frontier Labs have been supporting emerging media artists for a few years now, growing a small but powerful network in the process. Recently, the UK has made real strides in some of these areas with StoryFutures focused on the training side and Creative XR funding some fantastic projects like Darren Emerson’s Common Ground. But as Crossover Labs’ Mark Atkin has noted, “There’s now money for content in the UK through organizations like Creative XR but no real focus on distribution. The venues are there. The work needs to be aggregated and made more accessible to the public. It needs to be talked about.”

Colinart agrees, “We need to see this work talked about in the New York Times.”

There are a few solid VR distributors — Diversion and MK2 for example (go France!)—but a lot of creators are figuring it out on their own.

On the exhibition front, Phi Centre is now working on a really smart touring strategy. They have worked with Spheres and other projects to take their beautiful Phi-specific installations to other spaces. They are now finding ways to show really big immersive pieces and tour them.

Phi Centre

design for Spheres

Phi Centre

design for SpheresAcademic institutions have also been very involved in the space as showcases, curators, critics, and incubators—including MIT’s Open DocLab, which is one of the organizations behind Immerse. Lance Weiler is looking at immersive work more generally at Columbia’s Digital Storytelling Lab. His lab recently convened a panel specifically about funding and exhibiting this work. It is heartening to hear about other academic institutions getting involved in this area and bringing much-needed expertise, support and, yes, money to the ecosystem. But, as always, it is important that this knowledge is shared abundantly and not trapped in silos or locked behind academic paywalls so that we can all benefit.

We’ll get there — or somewhere

I have a feeling we might end up somewhere a bit unexpected.

Perhaps the focus on VR headsets is a temporary blip and immersive, mixed reality experience will look very different in the future. The one thing I have always been convinced about is that we will need to build the world we want to see. This includes in the VR space and whatever it becomes. We have a lot of work to do as Kamal Sinclair’s Making a New Reality research makes clear. I am excited to be working on a distribution strategy that will take Electric South’s VR projects as well as other work across Africa. I hope to build on all the knowledge and experience of so many people who are working hard to build this world into something real, accessible, and wonderful.

Thanks to Loren Hammonds, Dan Tucker, Shari Frilot, Mark Atkin, Caspar Sonnen, Arnaud Colinart, Myriam Achard, Jess Engel, Nell Whitley and Ann Roberts — you were all very patient with me as I tried to figure this out.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.