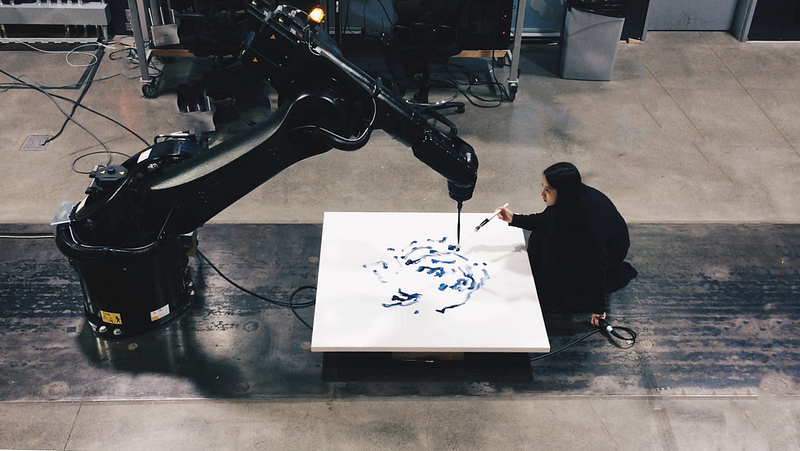

The Drawing Operations Unit:

Generation (D.O.U.G.) series by Sougwen Chung focuses on co-creation with machines. D.O.U.G._1

focused on a machine mimicking Sougwen’s drawing strokes, while D.O.U.G._2 focused on neural nets

trained on the artist’s drawings. Photo courtesy of Sougwen Chung.

The Drawing Operations Unit:

Generation (D.O.U.G.) series by Sougwen Chung focuses on co-creation with machines. D.O.U.G._1

focused on a machine mimicking Sougwen’s drawing strokes, while D.O.U.G._2 focused on neural nets

trained on the artist’s drawings. Photo courtesy of Sougwen Chung.One of the most provocative chapters of the Collective Wisdom report is titled “Media Co-Creation with Non-human Systems.” Authors Katerina Cizek and William Uricchio examine the possibilities and current practices of creators working with both living systems such as swarms of insects and machine-based systems such as artificial intelligence. Here are a few highlights:

Co-creation between human beings and non-human systems is a sticky matter, often moving into the speculative realm. Artists and provocateurs have nuanced relationships to the systems they work with. Not all of these artists subscribe fully to a co-creative model, but most of those we spoke with acknowledge the idea of co-creation. Their vision, methods, and raison d’être align with so many of the methodologies apparent in other forms of co-creation, which we define as working within communities and across disciplines.

At its best, co-creation allows artists and media makers to explore the hubris of humans positioning themselves as the planet’s only sentient beings. Such practices offer a hands-on heuristic to explore the expressive capacities and possible forms of agency in systems that have already been marked as candidates for some form of consciousness. Only by probing those possibilities will we be able to move beyond blanket assertions or denials of agency, and critically interrogate ourselves in the context of other possible forms of intelligence.

Comparisons between animals, machines, and humans are nothing new. René Descartes, a foundational figure in 17th-century Enlightenment thinking, compared animals to automata. He asserted that only humans were capable of rational thought and operated as conscious agents, while animals simply followed the instructions hardwired into their organs. Only at the end of the 19th century did a more nuanced view slowly begin to take root, as Charles Darwin’s notion of mental continuity across species found adherents.

Indigenous scholar and new-media artist Jason Lewis and his collaborators, write in an MIT-published essay that Indigenous epistemologies are “much better at respectfully accommodating the ‘non-human.’ ” He cites Blackfoot philosopher Leroy Little Bear to suggest that artificial intelligence may be considered on this spectrum, too: “The human brain is a station on the radio dial; parked in one spot, it is deaf to all the other stations … the animals, rocks, trees, simultaneously broadcasting across the whole spectrum of sentience.”

Over his long career as an artist and professor in computational art, Ernest Edmonds has revisited the question of whether computers can replace artists many times, always ending at a negative answer. We asked him if the relationship might be better described as co-creative, and he rejected this model too. “Art is a human activity for human purpose, for human consumption, consideration, and enrichment. And the making of the art is as much a human process as the consumption of it. And so, I would say that if machines could make art for machines, that would be fine. But it would not necessarily have any relevance whatsoever to human beings.”

Like Edmonds, Joseph Ayerle (a new generation artist and photographer), rejects co-creation as a way to describe his work with AI. He is the first artist to use “deep fake” technology in a short film, using off-the-shelf AI to map a face from 2D photographs onto 3D-modeled representations of other peoples’ bodies. “I was at the beginning a little suspicious. I worked on a separate PC, not connected with the internet,” he told us via email, “But bottom line: It is just a tool.” He wrote to us that AI may “create, but it is not creative.”

In music, David Cope was one of the first to explore the potential of AI, which he turned to when he suffered a case of writer’s block in 1980. He built Experiments in Musical Intelligence (which he calls “Emmy”), an AI which mimicked and replicated classical music styles, mostly of dead composers. In our interview he told us he did not describe his relationship with the now-retired Emmy as particularly co-creative, but he would say so of his work with another AI, Emmy’s “daughter,” which he calls Emily Howell. He describes their interaction as conversations: “That is, I work with her and she suggests things… I tell her what kind of things I want to compose or write or do or whatever, and she has a database just like EMI does, and the material in that, for her, musically, is all of her mother’s music.”

Anthropomorphizing AI systems is a playful co-creative model adopted by other artists as well, especially those interacting with robots. New York-based artist Fei Liu built herself a robot boyfriend she calls Gabriel, and has loaded him with large collections of text messages from an ex-boyfriend. She performs with the robot, fueled by an AI system that takes existing text and creates new sentences. She says for now Gabriel is “ex-dominated,” but eventually that will change. “In terms of his internal systems, it’s like he has preferences. He has likes and dislikes. And then [his mood] is affected by, this is something I’m playing around with … a variable in the code, which is called the ‘self-love variable.”

Much of the important work in AI projects reveals the limitations and dangers of relying too much on these systems, exposing the potential new cultural and political landscapes they could create if they remain unchecked, unregulated, and publicly misunderstood. Most of the co-creators we engaged with aim to turn these systems towards alleviating inequity and injustice at a digital and planetary scale.

This article is part of Collective Wisdom, an Immerse series created in collaboration with Co-Creation Studio at MIT Open Documentary Lab. Immerse’s series features excerpts from MIT Open Documentary Lab’s larger field study — Collective Wisdom: Co-Creating Media within Communities, across Disciplines and with Algorithms — as well as bonus interviews and exclusive content.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.