Finding inspiration in the corner of the internet where torrent trackers, MEGA uploads and other bootleg networks thrive

An

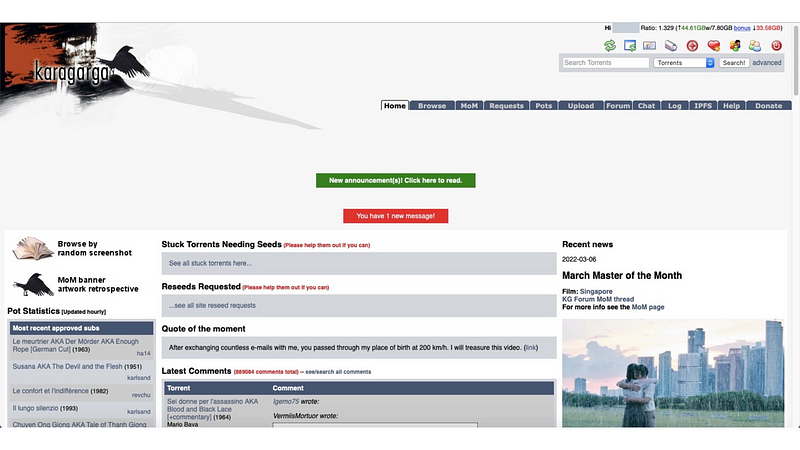

anonymized screenshot from the landing page of Karagarga, an exclusive torrent tracker for

cinephiles

An

anonymized screenshot from the landing page of Karagarga, an exclusive torrent tracker for

cinephilesThe circulation of nonfiction films online exists in both commercial and bootleg forms. Addressing the former, in February 2022, 16 independent filmmakers announced that they had formed Missing Movies, a working group dedicated to advancing the cause of preservation for films in danger of being left behind. They are specifically concerned with titles that have fallen through the gaps in the current entertainment landscape, which promises unlimited choice via streaming platforms but in fact offers less than what one could prospectively find at a video store during the heyday of VHS. As the group’s manifesto puts it, “Thousands of movies are either completely lost or are deemed too small to warrant the expense, and thus are completely unavailable. This is especially true of work created by women and people of color. As a result, we end up with a skewed history of filmmaking and crucial gaps in our cultural knowledge and legacy.”

To drive this point home, the group offers a preliminary list (they’ve promised to expand it) of films that are both out of print and unavailable on any streaming service. Notable entries include acclaimed works like Ossie Davis’s Black Girl (1972), Elaine May’s The Heartbreak Kid (1972), and Mira Nair’s Mississippi Masala (1991). (As a sign of how quickly these winds can shift, Mississippi Masala is finally getting a restoration and will soon be on the Criterion Channel.) The group does not make any special mention of documentary, but lists nonfiction films such as Ali, the Fighter (William Greaves, 1975), The Memory of Justice (Marcel Ophuls, 1976), Home of the Brave (Laurie Anderson, 1986), and Eat the Document (D.A. Pennebaker and Bob Dylan, 1972).

As docs are relatively sparse among the high-profile restoration efforts in recent years, the need for such archival work in this field is even more pressing. The sobering case of Eyes on the Prize, a seminal educational series only partially restored and available because of rights issues, is instructive. The few notable recent nonfiction re-releases, like 1959’s Jazz on a Summer’s Day, 1972’s F.T.A., and 1972’s Nationtime, were supervised by IndieCollect, which is dedicated to precisely the kinds of films Missing Movies seeks to champion.

The Alternative Is Karagarga and Its Bootleg Networks

And yet, there is one way to digitally access most of the documentaries on Missing Movies’ list. If you are a member of the torrenting site Karagarga, a quick search will bring you Anderson’s concert film, or Ophuls’s epic meditation on the cultural trauma of war, among many thousands of other titles. There is a small learning curve to the operation of a torrenting client (and one should probably also use a VPN as well), but once you get the hang of it, it’s easier than navigating most corporate streaming platforms. Unlike many torrenting communities, “KG,” as it’s known, maintains a high standard for file quality and specifically curates a selection of rare, foreign, and otherwise obscure films.

While KG’s membership is exclusive, a wider network of cinephiles has grown around it on social media, especially on Twitter. You might not have a KG membership, but you might know someone who does, or someone who knows someone. It’s possible to take advantage of KG through a complex series of negotiations by finding out what files are available, who has which, or who can get what. (In order to keep data flow at a reasonable rate, every KG member operates under restrictions for how much they can download, so no one can simply obtain hundreds of titles on a whim.) In a similar manner, certain Twitter users will post timed links to MEGA folders containing files for download. (This is how I recently obtained over two-dozen otherwise impossible-to-find Tsai Ming-liang shorts.) This community, entirely ad hoc and homegrown, has created a kind of stochastic, crowdsourced form of archival practice.

I spoke with one prolific MEGA uploader who is also studying film preservation and archiving in grad school. According to her analysis, “Torrent infrastructure has some really interesting implications from an archival perspective. Allowing files to be decentralized, existing in identical form on a number of different systems, is to me their most significant benefit. It requires a lot of trust in users to maintain those files, but if you can manage that, you’ve got the potential for a whole lot of backups.”

Justifying the Risk

The one hitch, beyond securing a hard-to-get invitation to more exclusive trackers like KG, is that none of this is, strictly speaking, legal. While it’s unlikely that any high-powered lawyers are on the hunt for people obtaining copies of films whose rights have mostly lapsed, piracy may be an uncomfortable prospect on basic ethical or moral grounds, particularly when it comes to works that have some level of availability. In her book Ten Skies, Erika Balsom admits that the only way she could watch the titular film by James Benning over and over to analyze it was to pirate it:

Ultimately, seeing something is better than not seeing anything. When I mentioned to Benning, not without some hesitation, that I had found the film on YouTube, his response was, ‘Sharing is caring.’ He seemed fine — happy, even — that it was out there. The bootleg offers a degraded form of access, sure, an experience of unabashedly inferior quality, yes. I doubt anyone would come away from watching it with the feeling of having had a powerful aesthetic experience. Yet its value is not to be dismissed entirely…

For rarer films, in many cases, if they were not being pirated, they would not be getting seen at all. As my source put it, “These sites save films that have no shot at mainstream release, often going so far as to subtitle non-English work that would never get official translations. There is no archiving without accessibility… I have seen so many films I love because someone took the time to share it with other people when no one else would, and to keep it safe when it might otherwise disappear. To me, that’s the archival spirit in action.”

The existence of this “archival spirit” is a particularly vital question for interactive nonfiction. Frequently, such works are impossible to access after they’ve made their rounds through film festivals and museum installations. If they aren’t put on marketplaces like Steam (where they are frequently misunderstood by users), how can they be distributed? Obviously, there are additional technical considerations around equipment, file formats, etc. But appreciators might do well to look to the example set by the Karagarga/Twitter/MEGA community, which found ways to circumvent their own obstacles to create a thriving corner of the internet where rare works are kept alive.

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and Dot Connector Studio, and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.