The Leap

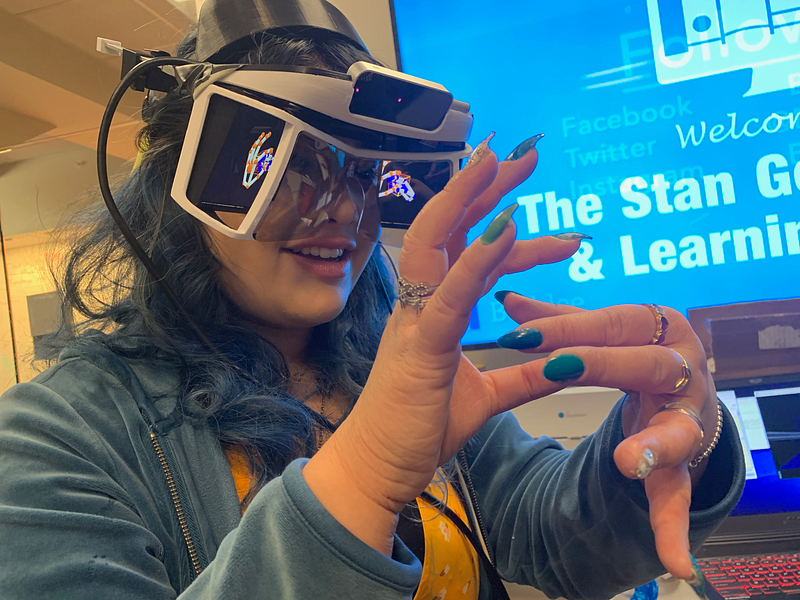

Motion Project NorthStar headset captures Blythe Schulte’s hand motions. Photo: Lori Landay

The Leap

Motion Project NorthStar headset captures Blythe Schulte’s hand motions. Photo: Lori Landay

Data capture is becoming ever more central to media making, whether it is performance capture for acting and animation, screen capture for machinima and animated gifs, 3D scans of physical objects to make virtual models for games or virtual art, or recording and reusing sound. Machine learning is intelligence capture. Algorithms process big data to capture users’ preferences and habits, and predict future outcomes. More than remixing, the concept of capture highlights the acquisition of image, sound, movement, practices, and choices.

Capture provides the data that enables prediction of what could happen next. Places, people, and things are captured into simulated environments, avatars and characters that populate them, and the objects with which they interact. Capture transforms what exists materially and what is created digitally, looping between abstract and concrete, 2D and 3D, photorealistic and iconic, creation and destruction, actual and virtual. As we watch, listen, play, and create in captured experiences, how are new realities and new ways of being created? What is captured? By whom? What can be released? What can evade? Or escape? Can we capture reality without being captured?

I’ve been working on this idea since my sabbatical project on Animation and Automation in 2015–2016. I presented on it at HubWeek in Boston at the VR/AR/MR session we hosted at Berklee organized by Divyanshu Varshney. I know the project encompasses the topics of avatars, performance capture, machine learning/artificial intelligence, robotics, non-player characters, volumetric capture, virtual world platforms for teaching, learning, entertainment, gaming, social interactions, and more. What’s being CAPTURED is the sum total of all that cinema, multiplayer games, installations, happenings, music, live performance, intermedia, interactive fiction, Dungeons and Dragons, social media and its big data, social networks, and more and more . . .

It’s the map in Jorge Luis Borges’s paragraph-long story, “On Exactitude in Science,” but it is not in the form of a map. I am still struggling with what form the project should take. Is it written? I do have a book proposal for it. Or do I sketch it, or talk it with motion-captured wild gestures? Oh, yes, as an avatar! Or, is it, as I suspect, an entire virtual environment? Even better: a class with students who are experimenting with the emerging technologies that we can use for capture, and we explore the topic together in projects that combine creative and critical aspects. Well, how the hell do I do that? (I actually have a lot of ideas for how to do that.)

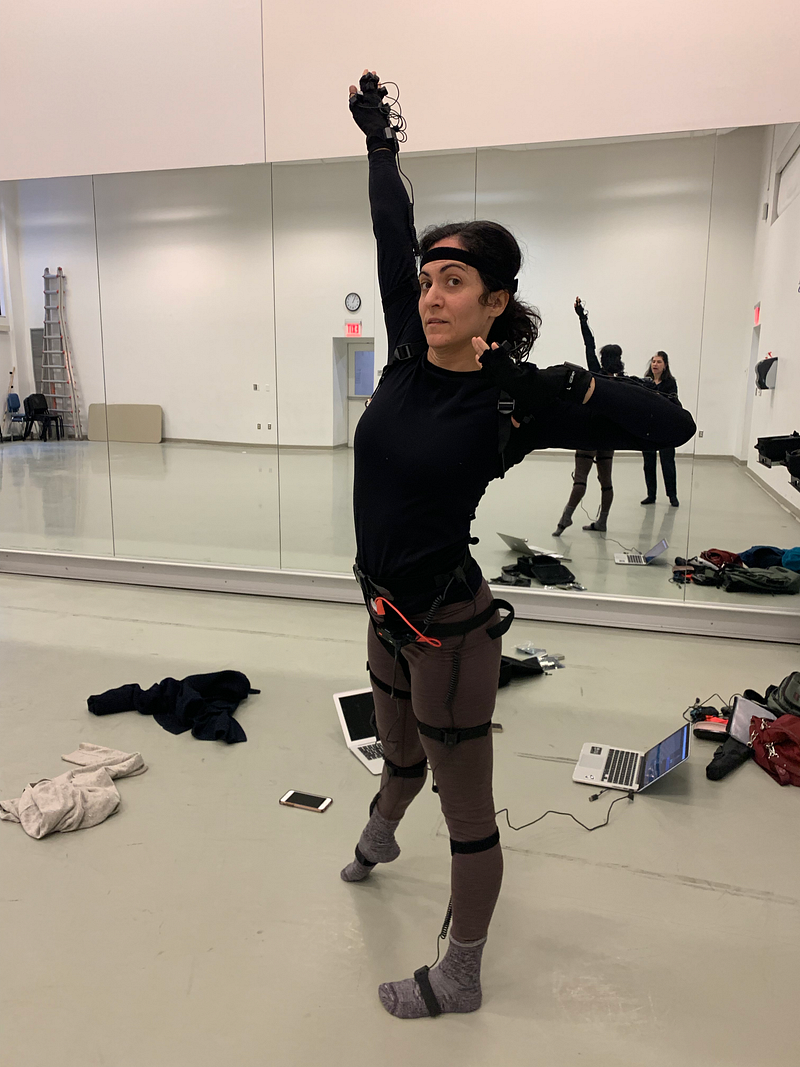

Alissa

Cardone and Lori Landay doing motion capture in the “mirror

of performance” at Boston Conservatory at Berklee. Photo: Lori Landay

Alissa

Cardone and Lori Landay doing motion capture in the “mirror

of performance” at Boston Conservatory at Berklee. Photo: Lori LandayI do know it has to do with virtual subjectivity, which starts with the experience of being in a body. In two-dimensional screen-based experiences in which you’re represented by an avatar, whether first-person or third-person (when you see your avatar), you have to imagine being in the environment. Experienced with a headset in a 360-degree environment in which you are in the middle, you are in the first person. You can look down and see an avatar body, or look in a mirror (and studies at Jeremy Bailenson’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab at Stanford suggest that seeing your avatar in a mirror can be part of an effective experience as an avatar). It’s what the 1999 movie The Matrix called “residual self-image” that matters here, what you think you look like in your head. I don’t believe that people always (or ever) have an “objective” residual self-image, but that it is subjective, filtered and shaped by the experience of embodiment. Virtual experiences can use the differences between the person’s residual self-image, their imagined virtual self-image, and whatever they see when and if they see their avatar in interesting ways. Interactive and immersive art has enormous potential for playing with the multiple variations of material and virtual bodies and subjectivities we can experience. (I wrote about this in an essay about virtual art.)

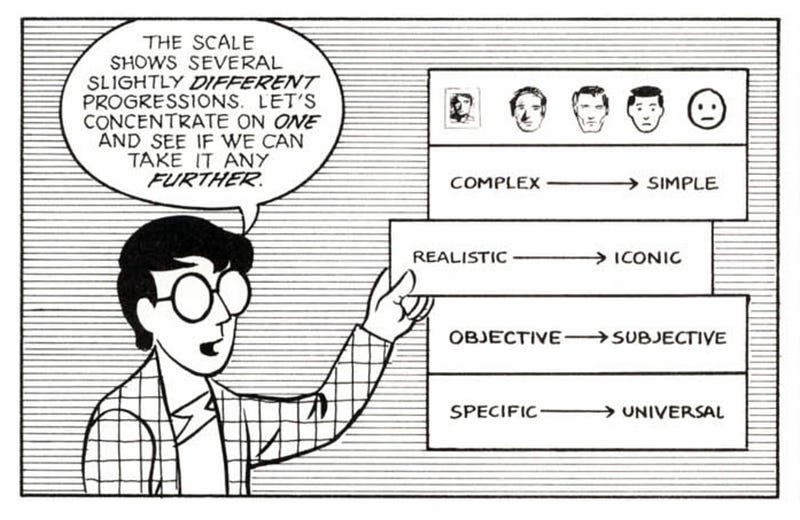

Until yesterday when I saw the Codec Avatar project video from Facebook Reality Labs that showed an avatar that was indistinguishable from the person it represented, I did not think that capture would come so fast. Of course, Facebook isn’t rolling out those avatars next week. For some time, we will have our cartoony representations that can hit the sweet spot between abstract and pictorial that Scott McCloud drew about in Understanding Comics.

Scott

McCloud depicts the scales of level of detail in Understanding Comics, one of the

smartest books ever.

Scott

McCloud depicts the scales of level of detail in Understanding Comics, one of the

smartest books ever.The journey to the left from simple to complex, iconic to realistic, subjective to objective, universal to specific requires advances in several fields beyond avatar capture. A couple of seconds of the codec avatar data takes up over 500 gigabytes. But the real-time photorealistic capture is coming, and so it’s time for me to get cracking on CAPTURED, in whatever form it may take. A lot is gained by chasing the real. But something is lost, as well. What does it mean to capture, to be captured? And how do we get a new answer to the old question: who decides who is doing which?

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.