An interview with Postcommodity on hacking soundscapes and Indigenous technological self-determination

Postcommodity is an Indigenous interdisciplinary arts collective based out of the American Southwest. Led by Cristóbal Martínez and Kade L. Twist, the collective structures its creative practice in immersive, interdisciplinary, and large-scale sonic, visual, and architectural installations.

Their most recent project, Let Us Pray For The Water Between Us (2020), displays a massive industrial storage tank refashioned into a self-playing, “breathing” percussive instrument, in the middle of a pearly white, Euro-Western museum rotunda. With this project, Postcommodity celebrates the living, breathing Indigenous stewards of water, air, and land in the Minnesota region and beyond, redefining whom a space can and should honor. As displayed in this piece, much of the collective’s work builds off “commodity art” traditions of Native communities, introducing experimental technologies into physical and sonic installations.

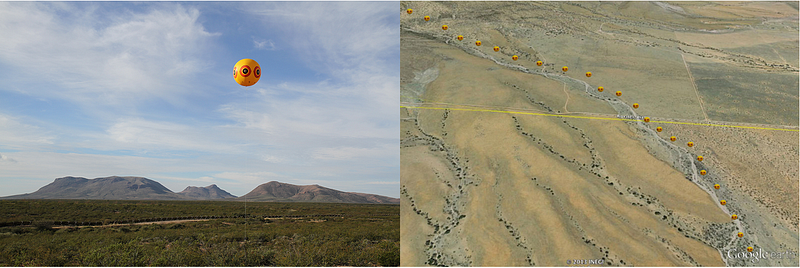

Housed in both public spaces and fine arts institutions, Postcommodity’s works are accessible to a wide range of audiences, creating portals that showcase Indigenous artistic traditions, while re-Indigenizing the historically contested sites on which they build their pieces. One of their most ambitious works is the Repellent Fence (2015), a 2 mile long land-art installation of tethered balloons that floated 100 feet above the desert landscape bisecting the US-Mexico Border. These balloons displayed Indigenous colors and iconography, bringing to attention the complex realities of the border experiences of Indigenous peoples which exist beyond the physical and legal constructs of a nation-state.

An artist

study (left) and Google Maps sketch (right) of the Repellent Fence intersecting the

US-Mexico border near Douglas, Arizona and Agua Prieta, Sonora. The balloons in this ephemeral

land-art installation were enlarged replicas of an ineffective bird repellent product. (Source: Postcommodity)

An artist

study (left) and Google Maps sketch (right) of the Repellent Fence intersecting the

US-Mexico border near Douglas, Arizona and Agua Prieta, Sonora. The balloons in this ephemeral

land-art installation were enlarged replicas of an ineffective bird repellent product. (Source: Postcommodity)Rather than see tradition and technology as diametrically opposed, Postcommodity situates its work at the center of both, disentangling the very notion of tying artistic value to technological progression. Instead of competing with or “replacing” art sold in Indigenous communities today, their high-tech, non-commodifiable work instead critiques the institutions that reduce Indigenous art to interchangeable artifacts — it’s all a part of Postcommodity’s narrative of “Indigenous technological self-determination.”

In this conversation with Martínez, we examine Postcommodity’s The Point of Final Collapse (2019), a semi-permanent sound installation that critiques the construction of the Millennium Tower in the SoMa District of San Francisco. Despite its grand appearance, the building, built on infill and sinking at a constant rate every year, is in a state of ongoing precarity. Every day from 5:01 to 5:05 pm, until the Millennium Tower is demolished or fixed, the installation floods the surrounding North Beach area of San Francisco with healing binaural beats and chakra sounds modeled as a function of the Millennium Tower’s sinking. Throughout the interview, which has been edited for length, we delve into Postcommodity’s artistic process, pedagogy, and politics.

The Millennium Tower. (Source:

Postcommodity)

The Millennium Tower. (Source:

Postcommodity)Julie Fukunaga: What goes into conceiving an art project at the magnitude of The Point of Final Collapse?

Cristóbal Martínez: Each Postcommodity project is unique. As an Indigenous artist collective in the 21st century, there’s no one singular and consistent aesthetic expression that encapsulates the diversity of issues we might engage in. What is the narrative of a place and the people situated in that place? What sorts of aesthetic responses might we be able to produce to communicate that narrative back out but through the lens of our Indigenous worldview as a collective? We never come to a city with a project already in mind.

With The Point of Final Collapse, in 2016, the Harker Fund and SFAI offered us a career-defining commission that could really function as a launch pad to help us reach a new plateau of practice and visibility. We wanted to reflect back to San Francisco a consciousness of what it’s like to survive in a brutalist economic environment.

As a collective, we can go pretty far because we’re so interdisciplinary. We have strong computer science, experiential media design, and engineering skills. We’re linguists, rhetoricians, poets, artists, and musicians. We have a lot of experience in public affairs and policy, in the learning sciences and pedagogy. We have all these experiences across all of these ways of knowing in the world, and we can dream pretty big.

The Point of Final Collapse is a sound installation that focuses attention on the Millennium Tower, which is sinking and falling at a steady pace every year. To put it in simple terms, as the building is falling, the value of the real estate is rising, which is an incredibly irrational expression of hubris that everybody has to pay the price for. Everybody feels anxiety that that thing could fall, whether you own a unit in there or you’re on the street and homeless.

We had some experience with long range acoustic devices (LRADs) from previous projects. We wanted to imagine what it would be like to put this giant pair of headphones on a city and make the city listen collectively to an idea. The LRADs produce hyper-directional sound that can be aimed and targeted at specific locations, which also characterizes weaponized devices used by military and police forces for crowd control. We’ve always found it cognitively dissonant that a device that produces sound could be used to create discursive silence, so we thought about flipping the script, looking at how we could position these instruments of war into instruments of beauty.

But we really spent some time just listening to the voices of San Francisco. The big theme of San Francisco, of course, is this hyper-inflated economy, which is also interconnected with gentrification, socio-cultural homogeneity, and a great level of anxiety. It’s hard to reconcile the disparities between some of the most expensive real estate in the world to one of the largest homeless populations in the world. It’s also hard to hold space with the exuberance of such unparalleled luxury defying the land itself. The building is on one of the most unstable places on the peninsula, you know? The Millennium Tower was built on infill, completed in the middle of the housing market crisis. The fact that it was sinking, and tilting, became the ultimate metaphor for the 21st century and all of the challenges we’re currently facing in the world today.

JF: Can you tell me more about the technology behind the project?

CM: Our installation uses computational algorithms that parse data representing the sinking of the building and maps them to healing ASMR and soothing binaural beats. As the building sinks, their playback increases per unit of time, causing the experience of sound to be more dense. As the composition moves from a clarity of ASMR composition to a compression of sound, it drives up listeners’ anxiety.

We chose to play it for four minutes every day at 5:01pm because that’s the time in San Francisco for the Muslim call to prayer, happy hour, and rush hour. We wanted to find that moment when the city is the most alive. The most important aspect of The Point of Final Collapse is to demonstrate these logics of capitalism and show how they encode fear, desire, and the ability of the greater public to rationalize systems of power. Sometimes we internalize the economy because our bodies create market value. But there’s something interesting that happens in The Point of Final Collapse when you hear the sound from an LRAD; you hear it resonating in your body, within your head, but you can’t discern where it’s coming from. In that moment, you resonate with these chakra tones, this holistic healing sound. You’re literally embodying the feeling of a structure that is in the process of collapse.

It’s going to continue to play every day, until the Millennium Tower either stops sinking, it falls, or it’s demoed. Or it gets fixed.

The sonic LRAD installation for

The Point of Final Collapse, installed at The Tower at SFAI’s Chestnut Street

campus. As the Millenium Tower sinks, piece’s playback of ASMR sounds and binaural beats increases

per unit of time, increasing the sonic density. (Source: Postcommodity)

The sonic LRAD installation for

The Point of Final Collapse, installed at The Tower at SFAI’s Chestnut Street

campus. As the Millenium Tower sinks, piece’s playback of ASMR sounds and binaural beats increases

per unit of time, increasing the sonic density. (Source: Postcommodity)JF: Like you said before, you’re able to unearth and bring a critical lens to something that so many people take for granted in San Francisco, while so many others don’t have the luxury to do so. Could you speak a little bit more about your principles working within communities as an Indigenous collective and what is it like to be in a room making these decisions, doing this research?

CM: In order to make a work like The Point of Final Collapse, we had to identify a phenomenon that could serve as a container to hold all of these complex socio-cultural and political and economic issues that burden a society. And in order to do that, we use critical Indigenous research methodologies, which is put together by Indigenous Professor Bryan Brayboy and his colleagues. There are four ethics researchers are encouraged to follow. First, research should always be respectful. It should always honor relationships, there should always be reciprocity involved. And in that there’s always responsibility. So that means that your motives, your ideas, should be legible and clear to the public. Through the four Rs, we get to hear people’s stories, and we spend time sensing and absorbing as much of that as possible. A lot of times, this type of method for art creation serendipitously leads to learning about something like the Millennium Tower. And it leads to internal conversations within the collective that allow us to brainstorm ideas that are situated and contextualized within the narratives that resonate with those whom we meet, places we visit. That’s also a really important aspect of how we were raised.

JF: Sometimes creative technologists and artists can shy away from politics, whereas your projects do the opposite. How do you engage with technology and social practice?

CM: When you think about technology, the status quo is to think about the latest and greatest. For Postcommodity, we see technologies as tools that augment the body and manipulate the built environment. We realized early on that being able to leverage physical and digital media together allowed us to set the contemporary artistic grounds for “ceremonies” that are temporal and imaginative — fictional and non-fictional. We’re interested in taking these emergent technologies for which Indigenous people had no ideational input and figuring out: how do we hack, modify, reform, and rethink them in ways that make sense to us? Indigenous people have been building experiential media systems since time immemorial. You’ve got ceremonial complexes all around the world that do amazing things with images, sound, smell, touch, movement, and interaction. We just knew that we needed to acquire the literacy skills so that we could extend that continuum of practice into our contemporary times.

JF: You’ve talked in the past in other interviews about how your work is not only cross-media and cross-nation, but also cross-time. So I’m curious to hear about how Postcommodity’s work brings together past, present, and future.

CM: I’m mestizo from northern New Mexico, so I have Genízaro, Chicano, Pueblo, and Manito ancestors. Where I was raised, there’s a certain quality to time. We’ve oftentimes spoken of our work as opening up portals, and these portals are temporary ruptures in space-time by which we can enter and we could observe reality in a way we couldn’t otherwise see. And we can come back from that space having recovered knowledge and having the opportunity to see the world, in some cases, for what it is and, in other cases, for what it could be. Through this ceremonial practice and worldview, time can be perceived and experienced and accessed in many different ways.

In other cases, one can recover one’s own dignity and also understand more deeply one’s relationship to oneself and one’s relationship to others. And at a spiritual level, this is potentially a way that we can see and bless each other and ourselves anew.

The work of Postcommodity is creating the space that allows us to transcend the “us versus them” narratives that are so prevalent in the world today. The only way we can do that is to syncretize our knowledges and worldviews with one another, and to be open and amenable to self-transformation. It’s also about each of us taking the time to implicate ourselves as part of the problems we’re experiencing.

Cristóbal Martínez serves as Associate Professor as well as the Chair of Art & Technology at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI). In 2015, Martínez earned his doctorate from Arizona State University in Rhetoric and Linguistics with a focus on emergent media within the context of Indigenous self determination and sovereignty.

Julie Fukunaga is a sociologist who studies all things identity and digital media. They are based between the Central Valley and Bay Area.

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.