Post #2 in the Making a New Reality series

By Kamal Sinclair

In 2014 I was asked to moderate a panel on 360° filmmaking at the inaugural Oculus Connect developers conference in Hollywood. As an executive of the Sundance Institute New Frontier program, which had premiered the first prototype for the Rift a few years earlier, I welcomed this assignment.

By this point, the majority of artists and creative technologists in the emerging media and DIY VR space I’d met had been fairly diverse and the vibe fairly egalitarian, so I wasn’t exactly prepared for what I walked into that day. I showed up to the large Loews Hotel ballroom wearing some “ethnic” looking patterned slacks, a computer bag on my shoulder and my naturally large curly hair in full flow and encountered what felt like a sea of white and Asian men in similar khaki/jean pants and button down shirt attire with drinks in hand. Out of the 150,000 developers who purchased the Oculus developer’s kit (DK1 or DK2) by 2014, these men represented the 0.007% that were selected to attend the conference.

I’ve worked in 25 countries, earned an MBA, and worked in the fine arts and Hollywood for twenty years, so being a minority in spaces of power was nothing new. However, this was the most strikingly homogeneous space I could remember.

My first instinct was to go sit at the coffee shop across the street until the program formally began, because I felt so out of place. Then I told myself, “If you leave there will be no one in the room that represents your intersection of identities (women, POC, etc).” I forced myself to make connections to as many people as possible, who all seemed to notice I was out of place but welcomed me with enthusiasm. I also saw a few women and people of color sprinkled in the crowd (shout out to Ryan Pulliam and Ikrima El-Hassan) and started to feel more comfortable.

By the end of the night I felt like a member of a secret, elite club about to fundamentally change the world. I was even invited to join an exclusive group of filmmakers (i.e. Chris Milk, Felix & Paul, Saschka Unseld, etc.) in a beautiful penthouse suite, where we got demos of the “best of” VR content on the best engineered Oculus Rift to date, and discussed the possibilities of story in VR with Werner Herzog. (Many thanks to Joe Chen.)

2014 Oculus Connect developers

conference

2014 Oculus Connect developers

conferenceHowever, this feeling of inclusion quickly vanished at a plenary session with all the top executives of the company. A woman from eleVR asked the panel if they had any plans to address the stark gender gap in the Oculus developers community, at least as it was represented by conference attendees. The executives responded with the argument that the company’s ecosystem was a meritocracy that did not look at race and gender in their hiring, community engagement or marketing practices. They emphasized that they were only looking at the “best of the best.” Based on the demographics of the Oculus community in the room, they seemed to be implying that “the best of the best” were exclusively white and Asian men. I felt like I received a virtual punch to the gut. Whoa! Ouch.

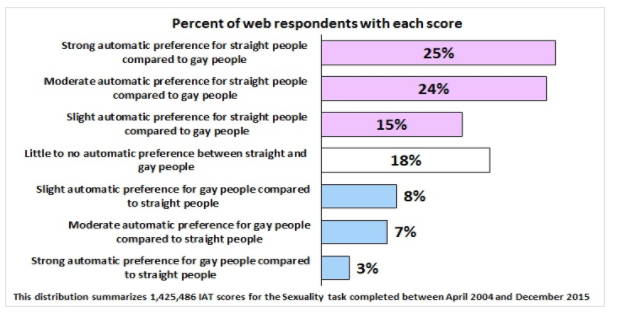

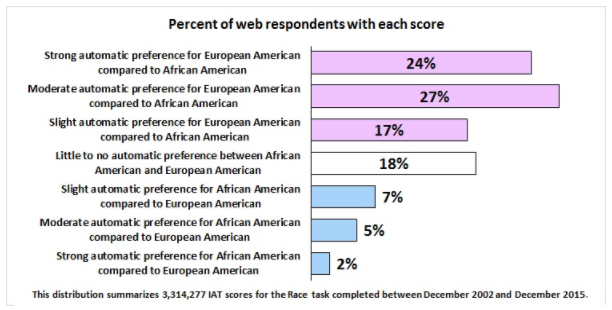

I shared this story with many of the interviewees of the Making A New Reality research in hopes of unpacking the lessons we could learn from this experience. Many echoed the notion that we are trying to awaken from more than 500 years of biased narratives in mass media. According to implicit bias research, very few of us can claim to be free of the superiority or inferiority complexes and unconscious biases that this long history has primed in our minds and hearts. We are programmed to accept a very limited set of types in any one identity group, and our brains quickly conflate very complex and dynamic people into pre-programmed and overly simple archetypes.

Results of the Sexuality Implicit

Association Test

Results of the Sexuality Implicit

Association Test Results of the Race Implicit

Association Test

Results of the Race Implicit

Association TestWhether these biases originate from some fundamental human instinct to create in-groups and out-groups that limit understanding between people, or the legacy of discriminatory structures created by brutally Darwinian motives, or are an outcome of scattered members of a family that forgot each other over generations of dynamic cultural production in vastly different environments — the reality is the same. People continue to perceive other human beings through the faulty lens of bias. In an interdependent global society with the superhuman capabilities of emerging media and technology, this is dangerous.

When asked to describe the first image that comes to mind when thinking of a film, technology, social media, science, or virtual reality innovator, most Americans, and perhaps most people, will describe a young cisgendered straight white able-bodied man. In the tech sector maybe his Asian counterpart would come in second (although the bamboo ceiling and model minority issues are important to note here).

Diversity in Tech by

WSJ.com

Diversity in Tech by

WSJ.com“I can’t speak directly, but I can say from observation that the image of the nerdy white or Asian coder is still a massive culture barrier…and it’s only gotten worse with the rise of Silicon Valley,” says Joseph Unger of Pigeon Hole Productions. He observes that “While film and TV have made strides, interactive hasn’t effectively recognized the contributions of women, communities of color, or non-industry producers.”

Even some of the most progressive or liberal people will rationalize this stereotype as having truth to it, not because they think white men have superior intellect, but because they recognize the legacy privilege and resources that are available to these men from a half millennium of colonization and a longer history of patriarchy. However, digging into the true origins of innovation greatly challenges these assumptions.

A few examples of people that bust the innovator stereotype include Oscar Devereaux Micheaux, a black man who significantly defined the medium of the film by making 40-plus independent films in the first half of the 20th century; Joan Clarke and Grace Hopper, two standouts among the legions of women who helped define computer science; Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Jackson, three black female mathematicians who helped America send men into space during the Space Race; Edie Windsor, a heroic gay rights activist whose case overturned the Defense of Marriage Act, who learned computer programming on the UNIVAC computer for the Atomic Energy Commission at N.Y.U. and was later hired by I.B.M. as a computer programmer in 1958; Evelyn Mirallas, the head of NASA’s 30-year-old virtual reality program; Martine Rothblatt, a transgender woman who founded Sirus XM, United Therapeutics and the Terasem Foundation; and Char Davies, Nonny de la Peña, Shari Frilot and Diana Williams, four women (three people of color and at least one queer) who have also played a significant role in catalyzing today’s virtual reality innovation cycle and industry.

Nonetheless, the story of innovation is told through the lens of those in power, who consciously or unconsciously tend to put themselves, or those with whom they identify, at the center of the stories. They have the resources to amplify their story and embed it into the consciousness of the general public, regardless of the more nuanced and diverse history of innovation. In the process, they often marginalize the stories of key figures involved in writing or coding the innovations that form humanity’s operating system.

In the worst circumstances, there has been outright theft of ideas or property. Even Alan Turing, who is at the center of our consciousness as an innovator, had to suppress and hide his identity as a gay man to remain a central, celebrated figure in the larger innovation narratives around the invention of computers and artificial intelligence that center straight, white, cisgendered, able-bodied males.

One anonymous contributor to this Making a New Reality research project shared this story in hopes of providing a concrete example of how the innovator stereotype perpetuates assumptions:

In 2016, I was asked to give an interview to a major journalistic media platform that was profiling a particularly prolific VR creator, who happened to be a white cisgendered straight able-bodied man. I was happy to do it and celebrate his incredible accomplishments. After the interview, I asked the producer what the title of the piece would be and they said, “2014, Year Zero VR.” I felt a shudder go down my spine. That was the first year this artist had presented anything in VR, so the title suggested that his work was the starting point for the medium. I politely pulled the producer aside and said, “I’d be very careful with a title like that. Not only is VR as old as gaming, but this particular wave of VR content innovation actually started in 2012 with Nonny de la Peña, a Latino woman. You could get a huge backlash from that title, especially since tech and media have a problematic history of erasing women and people of color from its history.” Thankfully, the story was never published, or at least not with that title.

One of the most concerning aspects of this dynamic is the significant cultural amnesia it creates in just a generation or two, sometimes in just a decade or two. Even social justice activists are vulnerable to the false narratives of history written by the privileged.

For example, another anonymous interviewee is an activist from one of the most effective policy change organizations and runs the department charged with intervening in film and media representation. They said, “We can not let emerging media follow the way of film, where we (African Americans) are 100 years behind!” I quickly stopped the person and said, “You are under the impression that we are 100 years behind in film when African Americans were essential to the very definition of the medium. Oscar Micheaux alone made 40-plus films in the first decades of film, and was a major innovator.” The interviewee was suddenly aware of the deeply ingrained, but false, narrative that they were unknowingly perpetuating.

Why this matters

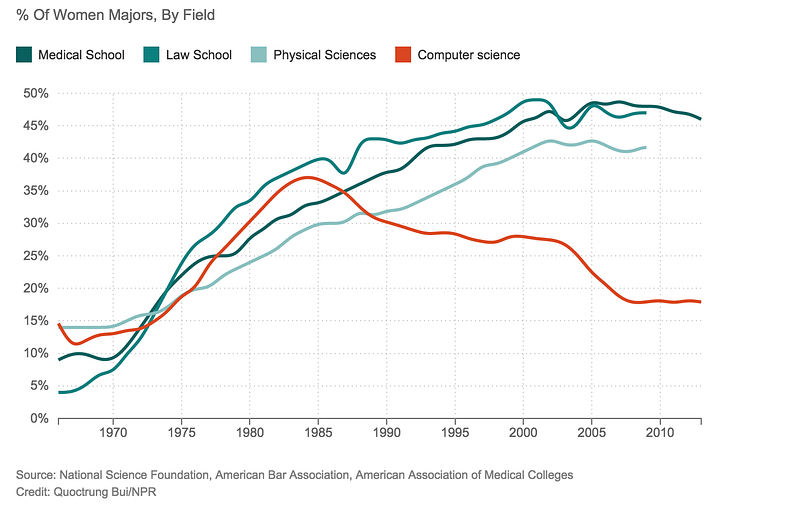

Failing to tell the story of diverse representation in any field is a deterrent to inclusion. For example, in the middle of the 20th century, the number of women entering the legal, medical, and computer fields was approximately the same across all three areas. In fact, in early computer science, women were entering the field at a faster rate than men.

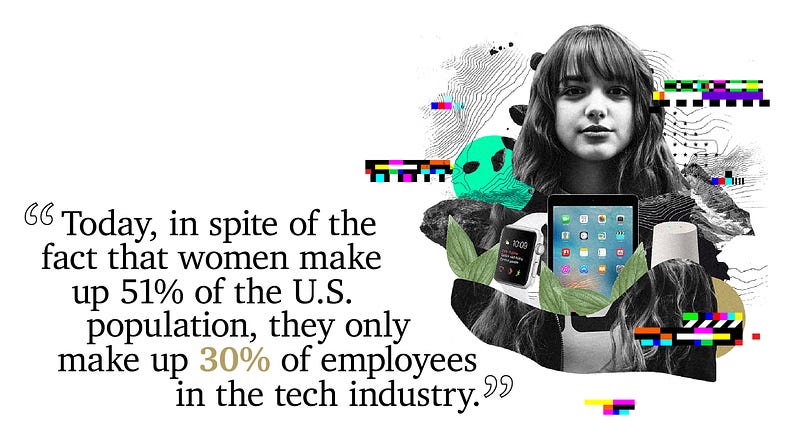

As of 2017, the ratio of men to women in the legal and medical sectors is almost at parity — but in the computer sciences, the number of women started falling significantly in 1983 and 1984. Today, in spite of the fact that women make up 51% of the U.S. population, they only make up 30% of employees in the tech industry (22% of the leadership and 15% of the technical positions). Why? The stories that we told.

If you look at the film, advertising and popular media of the 1980s, emerging computer technology was represented as an almost exclusively male domain. Films such as War Games and Weird Science, and marketing campaigns of big tech brands, such as Microsoft and Apple, positioned men and boys as the leads and heroes of the story. These stories cumulatively coded our collective consciousness to support one gender over another in that field.

We primed men to adopt and perform this new “tech geek” identity, while women were pushed to the margins of these nascent, computer-centric stories, encouraging them not to perform the new “tech geek” identity. What is even more concerning is that the repetition and wide distribution of these narratives created the development of superiority and inferiority complexes among men and women when it came to computer technology.

Planet Money’s “When Women Stopped Coding” episode described the computer science environment changing: Men started to haze women for not belonging and women (even if they had some of the highest grades in their class) started to buy into the notion that they didn’t belong and that maybe they weren’t smart enough to participate in the field.

This is an example of how stories code our performance or non-performance of identities. We were told a story that women were not tech geeks, and both the women and the men in “comp sci” environments performed or abandoned the “tech geek” persona accordingly. Studies on the Stereotype Threat have noted that priming someone with a stereotype increases the likelihood that they will perform that stereotype.

Artist Bayete Ross Smith

Often the spark of invention and innovation comes from the cross-pollination of ideas. So, diversity is actually an essential component of innovation. In fact studies done at the University of Chicago and Harvard University show a strong correlation between immigrants and American ingenuity.

One affecting example of how diverse perspectives inform innovation can be found in Omar Wasow’s contribution to social media. Wasow is a black man who created the pre-web community New York Online from his living room in 1993. This was the prototype for his 1999 social media defining network BlackPlanet.com. Before BlackPlanet, there were “web contact model” social media sites, such as the 1997 SixDegrees.com, but this was the first “social-circles model” site that was followed by Friendster in 2002, MySpace in 2003, and Facebook in 2004.

“Online social networks have come to define the modern Internet experience. Besides Facebook, services like Twitter allow people to keep in touch with folks they would otherwise never see or hear from. But before today’s popular networks allowed you to ‘like’ posts, ‘poke’ crushes, or ‘retweet’ celebrities, web-savvy African Americans were connecting on BlackPlanet,” writes Jenisha Watts, in Complex magazine. “Founded in 1999 by self-proclaimed geek Omar Wasow, 40, BlackPlanet became the most popular website for African Americans, and helped define what a new-age social network should be,” she writes. “People were allowed to build pages with photos, graphics, and info about themselves. But, more importantly, it let people connect with like-minded people.” In fact, “Myspace was derived from BlackPlanet,” Watts asserts, referencing a Business Week article in which the Myspace founders were quoted saying they “looked at BlackPlanet as a model for Myspace and thought there was an opportunity to do a general market version of what BlackPlanet was.”

I knew of Wasow’s role in establishing and innovating social media methodology, so when learning of the statistics that African Americans are over-indexed on Twitter (aka Black Twitter), I asked “Do you think black people have an affinity for social media because you, a black man, were one of the defining innovators of its methodology? Do you think you were subconsciously integrating the African diaspora’s ethos of ‘call and response’?” He replied, “Yes, explicitly. I was trying to create a ‘call and response’ website on the internet.”

This affirms that one of the most paradigm-shifting technology innovations and economic catalysts in the past 50 years was influenced by an African cultural norm. However, when researching social media innovation on the internet this history is practically invisible.

Appropriation in innovation

There is a related concern about how this history of appropriation impacts patterns of open creativity and creative commons culture in the future. Wasow emerged during an internet culture of open creativity and innovation, where communities of diverse people co-create art, technology, and envision the future together. This open source mentality matured into formal social contracts such as Creative Commons licenses, which allow participants to give back to the community. How do we maintain the open and generous environment that has allowed these communities to thrive, while mitigating the long-suffered pattern of unfair appropriation and misattribution that centers the dominant identity group and minimizes (if not eliminates) the contribution of the traditionally underrepresented groups?

Interviewee Jennifer MacArthur reflects on whether foundations can help support a more equitable system:

I don’t know that that’s possible, to be honest with you. That dynamic [of appropriation] is built into white, Western culture. That’s what they do. They appropriate. I’m sorry. That is a 500-year trend, right? So I don’t know that we’re going to break that with just making a decision collectively in the funder community. And when I say things like this, it’s really hard because I don’t say it out of anger. I don’t say it out of contempt. I say it out of a spirit of being willing to take a hard look at the cultural values of Western society and what it requires. In order for Western society to run and to function it requires a heavy dose of colonization, cultural appropriation, taking resources, and absorbing them into a thing.

In addition to concerns that co-creation spaces make underrepresented groups vulnerable to being left out of the innovation story, there are concerns that this also makes them vulnerable to missing out on the wealth-creation benefits. If a corporate interest — associated with the community or not — leverages an individual’s or a community’s ideas for economic gain, how does the person or the group benefit?

Repeating the patterns of the past?

Almost every Making A New Reality interviewee raised concerns that the current emerging media industries are already falling into many of the pitfalls that traditional media suffer in terms of creating and perpetuating biased narratives and behaviors. Not only does the majority of the content continue to represent diverse people by deficit-based identities (i.e. criminals, violent, primitive, traumatized, impoverished, victims, etc.), but its representation of asset-based identities (i.e. innovators, educators, business owners, problem-solvers, family members, heroes) are few and far between.

Failing to properly attribute positive aspects of diverse identities often leads to the suppression and exclusion of marginalized people that embody those positive identities. This is problematic in many ways, but in the innovation space this bias has a direct impact on the ability of traditionally marginalized people to benefit from the industries they helped to create.

How do we deal with something that is ubiquitous and in many ways invisible to those perpetuating the biases, both by the dominant and subordinate groups? Can we do better in this new and evolving media space? Disruptions such as personal computers, the internet, mobile devices, social media, immersive media, and machine learning only come along a few times a century. What interventions will we make in these technologies to ensure that a more just and equitable infrastructure emerges?

In the January 2018 issue of Making a New Reality, we will discuss these questions, list recommendations on how to mitigate these issues, and provide a description of some interventions that have been working to counter the innovator stereotype and pipeline/meritocracy arguments.

In fact, I have been a personal witness to how the “amplification,” “lean in,” “unconscious bias education,” “safe spaces,” and “inclusion” strategies have been changing the virtual reality community’s gender makeup over the past three years. Both 2016 and 2017 have seen continued efforts to showcase a growing number of women working and telling stories in VR and AR. A 2017 report with gender statistics for emerging tech shows the anecdotal buzz about “women ruling the virtual world” might have metrics-backed merit. That said, we still have a long way to go to achieve anything close to equity or equality, especially among other marginalized groups. Remember the “post-racial” proclamations during Obama’s administration and the current state of race in America? We need to be careful about prematurely claiming success.

Until the next issue, I encourage you to learn more about the major areas of concerns regarding bias in emerging media by reading these accompanying support articles. You will notice that many of the issues are not new, but as interviewees have identified, they are threatening the possibility of establishing a just and equitable future in media:

- Participation and Representation Gaps

- Pitfalls of the Meritocracy and Pipeline Arguments

- Grappling with Blind Spots: The thin line between empathy and patronizing attitudes

- Diversity Stigma

- Biased Education System

The Making a New Reality research project is authored by Kamal Sinclair with support from the Ford Foundation JustFilms program and supplemental support from the Sundance Institute. Learn more about the goals and methods of this research, who produced it, and the interviewees whose insights inform the analysis.

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.