A conversation with curator, film scholar and place-maker Greg de Cuir Jr. on desktop cinema aesthetics, handmade digital exhibitions and the metaverse now

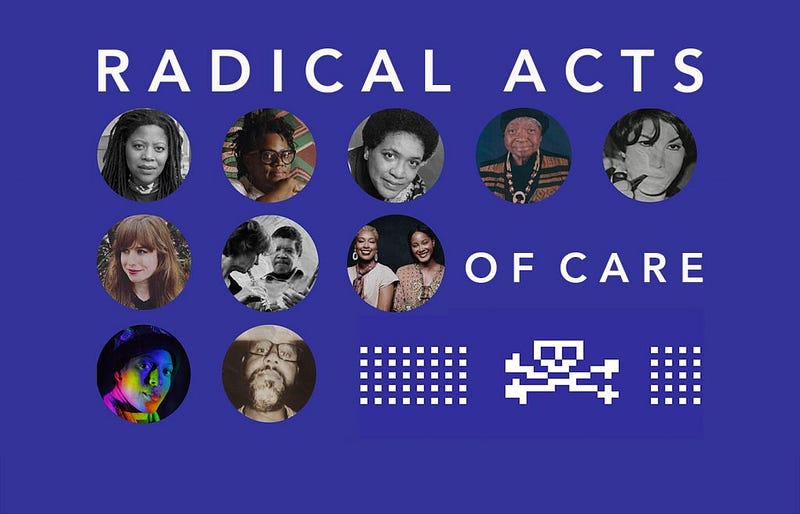

Wearing multiple hats in championing experimental moving image and developing how it circulates, Greg de Cuir Jr. is an independent curator, film scholar, the managing editor of the open-source, peer-reviewed journal of media studies NECSUS (Amsterdam University Press), translator and curator of the Alternative Film/Video Festival in Belgrade, where he hosts the Alternative Research Forum every winter. He’s curated the Black Light Retrospective for the 2019 Locarno Film Festival, the 2018 Flaherty Seminar with Kevin Jerome Everson, and at Anthology Film Archives (New York), Eye Filmmuseum (Amsterdam), and Kino Arsenal (Berlin), just to name a few of the institutions where he’s presented work.

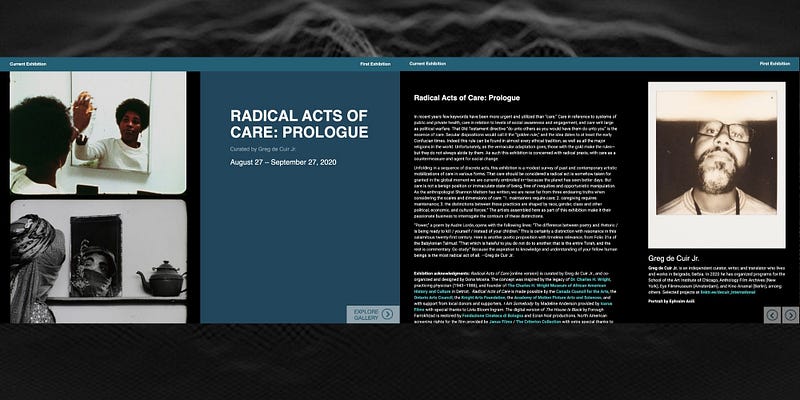

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, I noticed that de Cuir had uniquely adapted his nimble, thoughtful practice to virtual conditions. Though I was familiar with de Cuir’s scholarship on the Yugoslav Black Wave, Black experimental film, and interviews with filmmakers about film festivals, I was excited to encounter projects like “Radical Acts of Care,” hosted at the Media City Film Festival’s online exhibition space, the Dark Dark Gallery, from August 27–September 27, 2020. The digital-only exhibit featured a restoration of Forough Farrokhzad’s masterpiece The House is Black (1962) as well as new work and audio conversations recorded and created during the COVID-19 lockdowns from critics, musicians, artists and filmmakers, all presented within a website created just for the exhibit. Unlike the cookie-cutter streaming platforms used by most other “virtual cinemas,” online film festival portals, and video on demand, “Radical Acts of Care” unfolds like an accordion book with multiple chapters. Its format stood out to me as a patient and fully conceptualized response to the potential of digital exhibition of moving image work, matching the interrogation of the concept of “care” expressed in de Cuir’s program notes.

Since then, de Cuir co-hosted a conference on desktop cinema for the 2020 Alternative Research Forum, developed and facilitated a workshop on the same for the William and Louise Greaves Filmmaker Seminar (a project from Philadelphia’s BlackStar Film Festival), and started a digital consultancy called EXPOBLVD that produced Crypto Fashion Week with Universe Contemporary in February 2021, and is about to launch a follow-up called META_VS, running from April 5–10, 2021. META_VS is an expansive and ambitious digital art exhibition across three separate platforms, none of which will require special headsets or software to access, other than a web browser. The festivities also include drop parties and NFT auctions of new work, and drops that are NFTs.

Intrigued by de Cuir’s fluid curatorial and critical interests in claiming digital connectivity and new platforms for moving image artists, we discussed his many past and upcoming projects. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Screenshot

of the “prologue” and program notes pages for “Radical Acts of Care,” showcasing the horizontal

flipping structure of the exhibit

Screenshot

of the “prologue” and program notes pages for “Radical Acts of Care,” showcasing the horizontal

flipping structure of the exhibitImmerse: In the call for proposals for the Alternative Research Forum, you and co-organizer Miriam de Rosa positioned the conference as reading desktop cinema through Harun Farocki’s idea of the operational image. What I have casually seen in the US is that the types of images used in widely released desktop films have a slick, forward-momentum, swiping kind of energy. In addition, through the pandemic, we have had a greater exposure to video calls and Zoom aesthetics. Has this changed how things are being theorized and what you’re seeing, or are you going further back in history?

de Cuir: Depending on the community or the point of engagement, we can trace some similarities in desktop aesthetics. As a historian of film, I’m always interested in tracing historical trajectories of people like Farocki, and before him essayistic traditions and principles in television and video art. Where does desktop comes from? In the visual arts world, people make desktop work as artistic expressions. We can also talk about the academic edge of the videographic assemblage of desktop practitioners, how they speak about collapsing research and practice. Or we can talk about a net art or digital art. Then the desktop becomes much broader as a site of convergence. What did desktop look like when there were no desktops?

Desktop, like many things, has often been practiced and discussed and shown primarily through a white lens. I’m interested in cracking that lens a little bit and saying, well, people of color practice desktop also. Depending on how much we want to expand, we can also talk about YouTube videos and the desktop practices that are inherent there. Like you said, people now are used to video conferencing. Zoom very quickly and very seamlessly took over a lot of our frames of references. The desktop and the video frames within desktop are now a lingua franca that all people can speak and engage with.

Immerse: What are some of the differences that you are seeing, in terms of how people of color are utilizing this space? Are you framing this presentation at BlackStar’s Filmmaking Seminar as a form of recovery or excavation, getting people’s eyes on these creators and their works?

de Cuir: I’ve only engaged with the festival from a distance but I like the intersectionality that they’re practicing. I like how they’re bringing Indigenous peoples, which means different things in different continents and different regions, and peoples of color into the fold. I think that’s a really strong way to move the festival into the future. So I’m just trying to kind of mirror that with this program. Let’s see what people in North America, Africa, Europe, Asia, and South Asia are doing and add their conversations to the broader picture. Maybe there are going to be some members in the audience that don’t know anything about desktop or that genre of image-making we call desktop cinema. Where has that come from?

You can make the argument that one of the most important artists in recent years, Arthur Jafa, is making desktop cinema. “Love is the message, the message is Death” (2017) is a desktop film. He won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennial for “The White Album” (2018), which is a desktop work. Is it not? That’s all about internet archives and the interface of the desktop. So you could argue, therefore, that desktop cinema has already reached the highest pinnacle of the art world.

Immerse: In terms of where his work is being shown, I think about the music video that Jafa made for Kanye West last summer and how that has gotten millions of views on YouTube and it’s almost all found footage with a desktop aesthetic.

de Cuir: Yeah, we have to have wider discussions. The music videos that he made for Kayne and for Jay-Z is all stuff I watched on my computer. I’m old enough to remember MTV Raps and music videos on TV. And now I never watch music videos on TV. The main carrier now is the desktop screen, but if everything’s desktop, then nothing is desktop.

Immerse: One could even argue that watching a Kanye West music video on your desktop is a slightly retrograde way of encountering this work, because so many people only watch YouTube on their phones.

de Cuir: Exactly. We have to talk about the difference between the mobile screen and the desktop screen. We could talk about desktop cinema not as a genre or an aesthetic, but as a middle platform strategy. We can talk about Sundance and all these festivals that are practicing desktop cinema. It’s sort of a direct correlation to what they were trying to do IRL, but we could and should talk about desktop cinemas as the new cinemas. Who knows when this pandemic will end, but for a lot of people in the world, forget about cinema, unless you can watch it on a computer.

Immerse: I would like to shift our conversation to your new consultancy, EXPOBLVD, and your work on Crypto Fashion Week. This isn’t the first digital fashion week. What was interesting to you about this space?

de Cuir: I got into it through a colleague of a friend, Lady Phe0nix, the founder of Universe Contemporary. I’m advising on events and public programs for Universe Contemporary, which is a boutique consultancy specializing in crypto and digital art, dealing with the formation and management of collections. They also did a Crypto Basel, which I worked on, and where Miriam and I did a talk on desktop. The idea of doing a crypto fashion week came from the same principles, which is to intervene in a space and to gather some of these interdisciplinary actors together: designers, old school fashion, new school fashion, and technologists that don’t have anything to do with art or culture or fashion.

The idea is to gauge what’s happening with blockchain technology and how that’s influencing the way people are thinking about fashion from consumer, artistic, collectible and engagement standpoints. We’ll mix and mingle that with exhibitions, runway shows, discussions and exhibitions. It’ll all be completely online because this is not even the path to the future, it’s the path to the now. We’re building it independently, in the radical sense of doing everything decentralized and on our own.

Immerse: My sense of fashion week is that it is overloaded with brand sponsorships who bring in influencers and photographers and populate their runway front rows with celebrities. Will Crypto Fashion Week be browser-based? Will there be a VR access point so people can wear digital fashion while attending?

Promo image for Crypto Fashion

Week. Text reads: “22–26 February, 2021” and “Presented by Universe Contemporary x EXPOBLVD

Projects”

Promo image for Crypto Fashion

Week. Text reads: “22–26 February, 2021” and “Presented by Universe Contemporary x EXPOBLVD

Projects”de Cuir: Our tagline for the event is where the immutable meets wearable. So it’s all these things that you mentioned, first of all, in terms of platforms and the way people will engage with it. We’re going to be doing talks in Clubhouse, which is interesting not only because you can’t see anyone, but because it’s buzzy. Some of the people we’re working with have contracts with major fashion houses, magazines, or whoever they’re working for, where they’re not allowed to speak on camera without prior approval. Clubhouse also gives us an opportunity to include some people who can’t officially represent their company in the news media. In terms of the exhibitions and the runway shows, we’re planning on utilizing the metaverse and building some totally immersive virtual experiences.

In terms of your question about how much is this going to be like an IRL fashion week, there’s different schools of thought. Take film festivals, for example, there’s one school that practices, not explicitly — but a lot of festivals are just trying to replicate the IRL experience as closely as possible online. They’re in the battle at this moment to keep their festivals float, keep their audiences and scratch and claw for relevance in this world where everybody’s schedules are collapsed. There’s another school of thought that I think needs to be developed further, whether it’s the fashion week or the film festival experience. What should a film festival look like online? What could, and should a fashion week look like online? In other words, let’s use our imagination and let’s create a different world.

Immerse: It’s a forward-thinking perspective as opposed to one that strives to recreate a system that wasn’t working for everyone anyway.

de Cuir: We can try to recreate, but for me, that’s also a little bit of a lost opportunity. With “Radical Acts of Care,” the original idea was that it was going to be an IRL exhibition at a museum in Detroit, but it hadn’t been developed. I had never seen the space. We were free and untethered in that sense, but still the idea for me was, okay, I don’t want to do something that looks like this is just translated online. Not that I was so presumptuous to say, I’m going to pioneer a new exhibition that nobody’s ever seen. It’s more thinking about what works for this site, for this space, for these artists, for these works.

Immerse: Previously we had talked about how you wanted to carry over a handmade feel into that exhibit. At that point in summer 2020, we’d already seen institutions that had very courageously and laboriously ported their entire festival online on very short notice, from CPH:DOX to Visions du Réel. VdR instituted a ticket cap that was the exact capacity of the IRL theaters that the films had already been scheduled in, which was to me a strange practice at the time. But it’s one that has become standardized within the online film festival space — distributors and even filmmakers themselves are demanding ticket caps from festivals. Can you walk me through some of the decisions that you made for “Radical Acts of Care” with Media City Film Festival and what limitations or restrictions you had?

de Cuir: There were absolutely limitations and restrictions, but I embraced them I like to let fate step in and decide the way things need to be, and then I try to bend my creativity around those turns and corners and see where it leads me. Media City Film Festival is not a huge corporate or huge commercial festival. I worked hand in hand with Oona Mosna, the founder and director of the festival. Our team was a web designer and an audio producer. In some cases we were limited by the templates for the site because we didn’t necessarily have the time, money, or workforce to build something from scratch. We had to creatively work through the way you scroll through the exhibition in terms of the interplay between the vertical and the horizontal (the way the cinema screen or the way film strips progress or the way the desktop interface works).

We also tried to show pieces that fit this mode. Marietjie Pauw and Garth Erasmus from South Africa created sound pieces in quarantine, sending mobile app sound recordings back and forth to each other and created an experimental album using traditional instruments and a flute. Not only did their pieces speak this moment that we were living in, but people could also listen to those tracks while they were exploring other parts of the gallery. Every decision was made with Oona — we vibe off each other and improvised back and forth the same way that Garth and Marietjie improvise their music. The simplicity of the exhibition also hopefully helped people navigate through the chapters because they could take it and come back to it, but still feel that they have the larger topography of it in their mind.

Immerse: I thought it was really sensitive to how people use the internet to encounter work because of this episodic structure. I didn’t feel like I was obligated to encounter it all at once if I don’t want to.

de Cuir: I tried to write this exhibition the way I would write an essay and Oona is very into poetry. We didn’t want it to be a flat exhibition. Cross-disciplinarity is a way toward interactivity, for people be able to navigate that digital gesture and feel like you could hold this exhibition in your hand and really flip through it, almost like a book at your leisure. I forget about all the unique, interesting radical and independent programs from museums, galleries, or digital native spaces, whether it’s different apps, Instagram, or whatever. God, there’s a million things. Our hope was that some of these pieces would be interesting enough so people would actually want to come back and slow down their pace a little bit; a lot of what I do is “less is more.”

Immerse: The EXPOBLVD website is itself an act of curation in and of itself to list everything that you’re involved with. You also note decoloniality prominently as one of the services you provide. How did EXPOBLVD come about?

de Cuir: Operating independently with curating, writing, or researching here and there, you have to work on a lot of projects just to stay alive and to feed yourself and your family. A year or two ago, I wanted to organize my professional work more. I started the consultancy because I wanted to work on more projects on a strategic and conceptual development level rather than primarily doing things on a more granular level. Through the consultancy, I’m assembling teams and managing and organizing projects, but I’m still taking that hat off and putting on the hat of an independent curator and writer, writing essays and organizing exhibitions. As I grow in my career, I often need new challenges. That’s why I’m now getting into blockchain, digital fashion and working with nonprofits and foundations on building institutions.

Decoloniality intersects with all of those things because who I am, where I come from, the way I move, talk, and operate. I carry that within my spirit, my soul and my whole background. Whether you’re an arts institution, a film festival, a university, or a corporate brand, everybody’s trying to figure out this reckoning that we’re in socially, economically, racially, and ethnically. I’m from Los Angeles originally, and I spent a number of years in Hollywood literally working in diversity and multiculturalism. I believe principles of decoloniality and actions can tear down existing structures that have often oppressed people and create new ways to make an equitable society going forward. Sometimes I know I’m sitting in an audience of people that are like me, and I know they’re already going to like this because they saw me talk about this before. I very much often want to challenge people and organizations to see things differently and do things differently. And if I can do that, I can hopefully use that as a way to chip away at the earth and leave it in a tiny bit better shape, and hopefully other people will do the same.

This is a moment where people are, again, finding a lot of promise online in decentralization, blockchain, and these crypto spaces; people are very aware that these huge digital corporations are running a lot of our lives. People are seeing some ways of removing some of these structures that are controlling things or finding new worlds — virtual reality is one of those things. I know the architects of the internet say, “We’ve been through this before. The internet was supposed to be a great open space and look what happens.” That’s the Marxist lesson that we can take to heart: history repeats itself. Maybe now we’re in another moment where a new generation says, instead, “Hey, you know, I don’t have to do things the way you old folks who invented the internet did it, I’m going to build this safe space for my friends and my community this way.” That’s happening and will continue to happen. There are new playing fields that are wide open. Let’s see if we can do the right thing with them.

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.