Bronwin Patrickson and Tom White discuss urban design, video game realism, and 360 video in Nepal

The second conversation in our i-Docs + Immerse climate conversations pairs Bronwin Patrickson, a digital design researcher with a background as a transmedia practitioner, and Tom White, a visual journalist who teaches at Yale-NUS. Both firmly in lockdown and communicating across oceans — Bronwin in Wales and Tom in Singapore — they began by looking out their windows, then somehow segueing across immersive media practice, planetary health, 360-degree film, and drone scanning, realism in games, player agency, and finally coming full circle back to nature connectedness.

Where the first conversation — between Lizzie Warren and Michaela French — had wolves and domes, read on below for badger cubs and 3D villages in Nepal. — Julia Scott-Stevenson, i-Docs co-convenor

Tom White: I’m always interested in imagery around rewilding, especially in an urban context. What would a rewilded city look like? This is the view from my home office here in Singapore:

Bronwin Patrickson: We have fake grass in our backyard, which the landlord put in. Despite the potentially toxic dust, the vibrant green fluffiness of that lawn is strangely appealing. Our cat likes it. I wonder if we will ever be able to re-wild our cities when easy care is such a prime consideration for busy lifestyles. How are you tackling challenges around cities and the environment in your projects?

White: I have been involved in some research work with Professor Brian McAdoo at Yale-NUS, a geophysicist on disaster resilience and planetary health. We’ve started to use 360 videos and drone images to model immersive environments, exploring different ways of constructing narratives, and are in the early stages of tinkering with game engine environments to do this.

At i-Docs, I would have discussed our fieldwork in Nepal and Indonesia, working with local partners in these places and some of the struggles we’d encountered learning about immersive documentary methods on the fly. One of our aims is to develop methods that can be used by organisations with little budget, so I’ve deliberately tried to keep the work lo-fi, using relatively affordable gear. A key concept for me came out of discussions with Brian, around taking a holistic approach to the way we interact with our environment.

Patrickson: And are you seeking to engage the public in that approach?

White: That would form one aspect of it, yes. When we started working on this, I was reading Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics, which argues that we need to provide basic standards of living, and can provide decent comfortable standards without being extractive to the point of damaging the planet’s ecosystems beyond certain limits. So we started thinking about how to tell stories in a way that could engage with these complex dynamics.

Patrickson: Were you scanning during this project? So you could recreate it at other times if you wanted to?

White: We were using 360 video in some parts, and we were able to do a couple of drone scans.

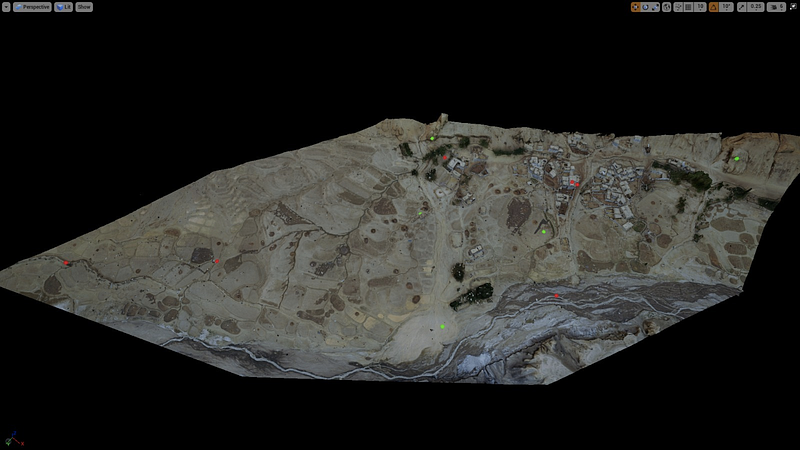

“This is a remote village that is

not yet accessible by road. You have to walk or take a horse. We took horses.” (White)

“This is a remote village that is

not yet accessible by road. You have to walk or take a horse. We took horses.” (White)

The drone images are processed to create a 3D model of the area. It’s pretty good. We worked with a 3D graphics artist to clean it up. The idea is that you can then virtually enter the space and have content in the form of 360 video, stills, or other info and data accessible. This is where the game engine is needed. I wanted to be able to gather content with consumer-grade gear, so these are Mavic Drones and GoPro and Insta360 cameras — not cheap, but relatively inexpensive when compared to a Lidar scanner.

Patrickson: I was watching a documentary called The Secrets of The Stones about archeology work in Ireland. By conducting geo-scans, a scientist had discovered a new, previously undiscovered ditch that encircled the Hill of Tara site… I’m not sure if we’re talking about the same sort of technology, but it would be fascinating to see what is revealed/created if the whole world can go out and start scanning itself. Have you shown the results to the locals? Or do you plan to?

White: One thing we will do is share it with partners in Nepal. We are trying to figure out how to do this in a low-tech way. Oculus headsets are still a rarity. Part of the problem here is working out who the audience is, and how best to allow them access. We’re still doing “observational documentary’” in some sense, going and collecting stories.

Patrickson: I work with a group of technologists who opted to develop a mobile application rather than VR for that reason, but there is still a lot to say for scanned VR environments. The UK group Scanlab has been doing that. My only experience of going into a real-world-shaped VR environment was Google Earth.

White: I think the holy grail of immersive environments is still the holodeck, and we’re all striving for that in some way.

Patrickson: Yes, Murray’s book Hamlet on the Holodeck is still seminal, still inspirational.

White: Tell me something about your experience in engagement. You mentioned that you had done work on playful design…?

Patrickson: I’ve analysed audience engagement with Shelter (an animal role-play survival video game) via YouTube Let’sPlay videos… In Understanding Comics, Scott McCleod talks about the importance of the space between the frames and the need to leave empty spaces for the audience to imagine. There’s a sweet spot between full detail, enough to render some sense of reality to a fantasy world, and the imagination that it takes to inhabit it.

White: I liked the aesthetic of Shelter. What do you think of the idea of games like Shelter striving for realism?

Patrickson: I’ve been exploring nature connection poetics in playful media. Images play a very big part, as much as mechanics. Surprisingly, images don’t need to be realistic to be evocative. You will never get the full, kinaesthetic effects of forest-bathing online, but you can simulate the mental influence nevertheless. The simplistic origami visual style in the game Shelter is a beautiful example of that.

In the game

Shelter, players inhabit the perspective of mother badger who must feed her babies and keep them

safe from predators and nature’s many challenges.

In the game

Shelter, players inhabit the perspective of mother badger who must feed her babies and keep them

safe from predators and nature’s many challenges.Anthropomorphism is a controversial topic. We need to more readily acknowledge that animals are not our pets, nor are they defined by our perspectives. But, as the players clearly show in my study of the Let’sPlay videos, anthropomorphism is — dare I say it — a natural instinct. We project to connect. Even romanticised, non-realistic presentation (as Shelter clearly is) has an important role to play in that process. Ideally, it helps to plan for ways to ensure that the projection can indeed become a pathway for deeper understanding. This is a huge issue both now and in the future that I’m in danger of simplifying here, but I do wish to acknowledge it at least.

White: When I started playing around with 360 cameras, I was struggling with how we might navigate 360 and immersive environments. I hadn’t really played games for years, and it was somewhat of a revelation to me to think in terms of game-playing when looking at documentary work… I saw recently that the cinematography of the film 1917 was inspired by director Sam Mendes watching people play first-person games and how they immersed even an observer.

Patrickson: I previously participated in a study of militaristic video games to test whether they were in turn militarising society, at least in terms of the way that they influenced attitudes. The answer to that question depended very much on how they were framed. If the world view of the game matched current day media rhetoric (e.g. remember talk of evil-doers?) the two reinforced each other; if not, there was a healthy disconnect between them.

Michael Frederickson at Pixar Animation Studios has made some compelling observations about the importance of awe in contemporary media. He consciously creates awe as a sort of engagement pathway within animated content, but the same is also true for documentary engagement. The challenge is for that not to become too manipulative. Designers talk about the need to support the sense of player agency. A game where anything goes is often not as fun, dramatic, or compelling as a situation where you only have two choices, and a lot is at stake….so the trick is to emphasise those choices to create a sense of agency, even if in reality the possibilities in play are highly choreographed.

White: One thing we discussed was having a “player” control the level of environmental change: You choose how bad the tsunami or earthquake is and you see the effects on the environment and people. We want to “gamify” info so that a viewer can explore the area and discover interconnections themselves… One of the ongoing discussions we have is how to take documentary content and use it as a catalyst for discussion, with that discussion than being embedded within the documentary content, so you have dialogue between local stakeholders and outsiders.

As a final thought, I would say that I hope the future is participatory and collaborative, and that to make that hope reality, we have to work very hard at re-imagining and restructuring the power dynamics at play. We do have some amazing tools for doing that, both practically and in the social and spiritual sense. We have an extraordinary window of opportunity to do so at the moment and I think you said it best: “We also need to undertake a cultural experiment and explore what it really means to be interconnected in nature…and deeply respect/value/celebrate natural rhythms and relationships.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.