An interview with Lucas LaRochelle

Lucas LaRochelle is a multidisciplinary designer and researcher examining queerness, technology, and architecture. Their practice explores interactions between the body, technology, and space. MIT Open Documentary Lab director Sarah Wolozin interviewed them about their project Queering The Map. Highlights from the interview were included in the Collective Wisdom report, but here we present a more in-depth look at Lucas’s approach to this project. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What is Queering the Map?

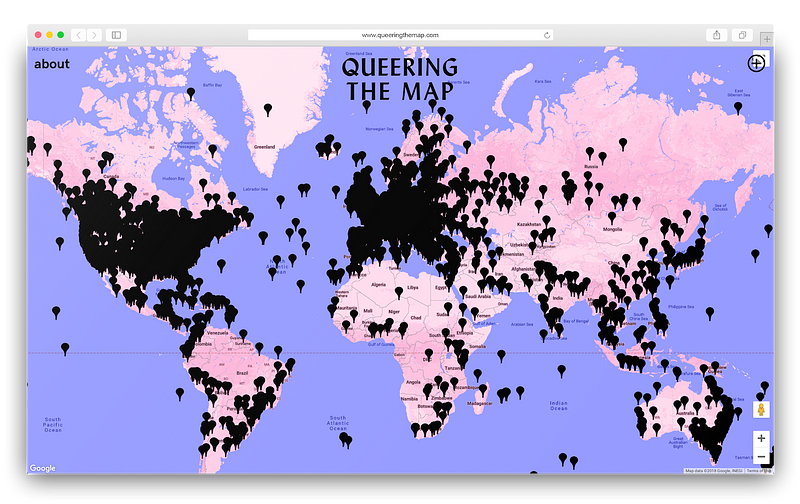

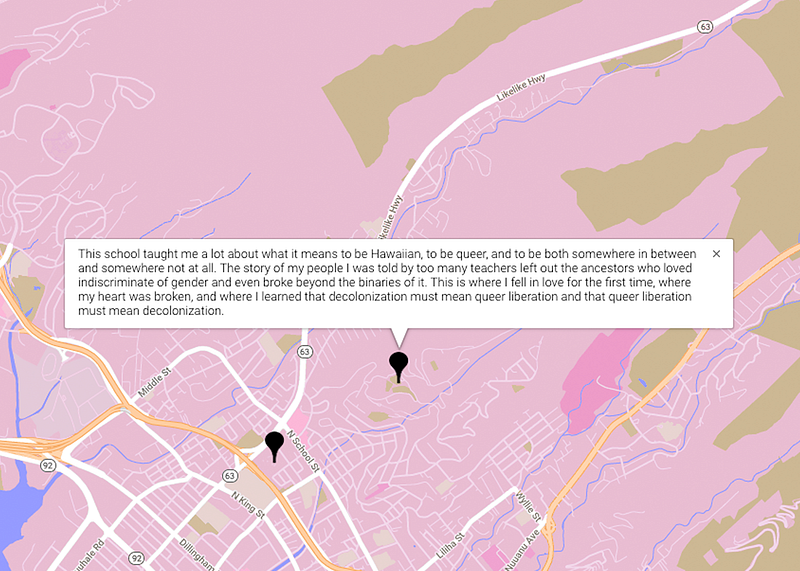

Queering the Map is a community-generated counter-mapping project that digitally chronicles queer experience in relation to physical space. The project collaboratively records queer life to preserve our histories and unfolding realities, which continue to be invalidated, contested, and erased. From collective action to stories of coming out, encounters with violence to moments of rapturous love, Queering the Map functions as a living archive of queer experience. Currently, it’s home to over 80 000 stories in 23 languages, from across the world.

Do you consider this project co-creative?

Definitely. My practice often engages in co-creative methods because I’m wary of individual authorship. Nothing exists in a vacuum — ultimately all ideas are the result of co-creation. I consider Queering The Map to be a co-creative archive. It is open to whomever has access to it and is interested in contributing to it. Posts are not curated (though they are moderated for hate, spam, and unsafe content) and the result is something that is fundamentally messy, contradictory, and confusing.

Queering the Map emerged from my interest in thinking about how space informs my understanding of my own queer experience. I recognize that my experience is one of privilege. I am white, able-bodied, and of a middle-class background — which is why a co-creative practice is so critical, as it facilitates a way to decenter myself and mobilize my privilege in order to benefit my community.

How do you co-create with people online?

For me, it’s been about building and maintaining a framework that enables co-creative storytelling. I would consider myself a facilitator. I have set up an infrastructure with which to co-create a digital archive of queer life. The opportunity to add to and complexify the contents of the archive is open to anyone who has access to the site.

Collaborative coding tools like GitHub are also instrumental to the co-creative practice, as they allow for a wider range of input outside of my geographic context. Currently, Queering The Map’s GitHub repository is private, though making the base code public and open-source is part of the future development of the project.

While digital networks greatly increase the possibilities for co-creating, the transnational world of Queering The Map,—having an online-only archive— excludes those who do not have access to the internet. So, it is of course not without its limitations.

What happened when the project quickly rose in popularity?

Within a period of three days in February 2018, it went from 300 shares to just over 10,000 shares on Facebook alone, which increased the number of points added from 600 to about 6,500. At first, they were mostly in North America and a few in Australia, but they quickly spread across every continent.

Following that three-day period, the project was spammed by Trump supporters, who injected malicious javascript code into the site that generated pop-ups reading “Donald Trump Best President” and “Make America Great Again.” I took the map down, and put out a call for help on the URL. Thankfully, because it had already generated so much attention, I received dozens of emails along the lines of “We’re queer coders and we love this project. How can we help get it back online?” Some of them set up a GitHub, and from there it was about a two-month process of working collaboratively to get it back online in a manner that was far more sustainable. Notably, a moderation system was developed so that hateful content could be controlled.

This development took Queering the Map from existing as a participatory project — in terms of me having the ultimate control over its infrastructure in the beginning — to a truly co-creative one. What was ultimately a prototype was put out into the community, who then identified its importance and helped to collaboratively re-construct it. This method of working is risky, but the payoff has been immense.

What are your broader goals with this project?

I first encountered other queer people in virtual spaces — encounters that were not available to me in rural Ontario. It is not an overstatement to say that these digital spaces saved my life. My overall intention with this project is to contribute to the life-sustaining force that is queer internet culture, to hold digital space for queer communities across the world.

One of Queering the Map’s goals is to contribute to discourses that think of queer space beyond places of consumption like bars, nightclubs, bookstores, bathhouses. As the proliferation of digital technologies radically reshapes the ways in which LGBTQ2+ folks access and create community, Queering The Map works to archive these otherwise ephemeral queer spaces. A fleeting glance of queer recognition, a T shot in a library bathroom, an MSN conversation with an anonymous online lover — these moments are themselves places of refuge.

The project aims to move away from thinking on queer space as fixed, and towards an approach to queer spacemaking that is rooted in action, as responsive and in flux. A queer approach to space understands that we cannot be queer in a fixed sense, but rather that we are doing queer through acts of resistance. To move away from the notion of a queer space as immovable, as settled — and rather to think of queer space as something rooted in the continuous breaking down of cis-heteropatriarchal, white supremacist, colonial, classist and ableist structures. This shift makes necessary a sustained engagement with the histories and presents of a place and its shifting political context.

This article is part of Collective Wisdom, an Immerse series created in collaboration with Co-Creation Studio at MIT Open Documentary Lab. Immerse’s series features excerpts from MIT Open Documentary Lab’s larger field study — Collective Wisdom: Co-Creating Media within Communities, across Disciplines and with Algorithms — as well as bonus interviews and exclusive content.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.