By Anandana Kapur

Inscribing the self in a world of

media monopolies

Inscribing the self in a world of

media monopoliesDecember 16, 2013: I remember that night in great detail. My editor and I were working on a film well past office hours. Stepping out only once to grab a cold salad and a coffee, I got home at the break of dawn the next day and promptly fell asleep. Barely 9 km away, Jyoti Singh, too, had stepped out the very same night. She was, however, waylaid, brutally raped and left to die on the streets. It was an ominous night.

Shock and anger in the aftermath of Jyoti’s death saw wave after wave of women take to the streets of Delhi. We were staking our claim to the city and to ourselves. Women stood shoulder to shoulder in compassion for each other and in resistance to violence against them. Disappointingly, media discourse around the protests grew hysterical and Delhi became the infamous “rape-capital” of the world. As a result, women were forced to constantly look over their shoulders “haunted by ghosts of past crimes.”

Mainstream narratives reinforced women’s anxieties and made their absence in public spaces seem rational, even desirable. That is when my dog-eared copy of Why Loiter (2011) — Phadke, Khan and Ranade’s investigation of women’s experience on the streets of Mumbai — began to look like a battle plan, as I desperately sought and underlined words to dissent with all of this, too.

Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?’

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the Cat.

—Lewis Carroll (1865)

As a filmmaker, I often asked myself — which way I ought to go from here? How could I explore the stories of the women who had spoken out from behind veils of passiveness?

The International Labour Organisation refers to them as “invisible women” but domestic workers traverse the cityscape everyday. Their employers—i.e. homemakers—may be privileged but are often silenced by tradition. Yet, they too experience love and loss in the multiverse named Delhi. Together, they negotiate and make new memories of the city everyday.

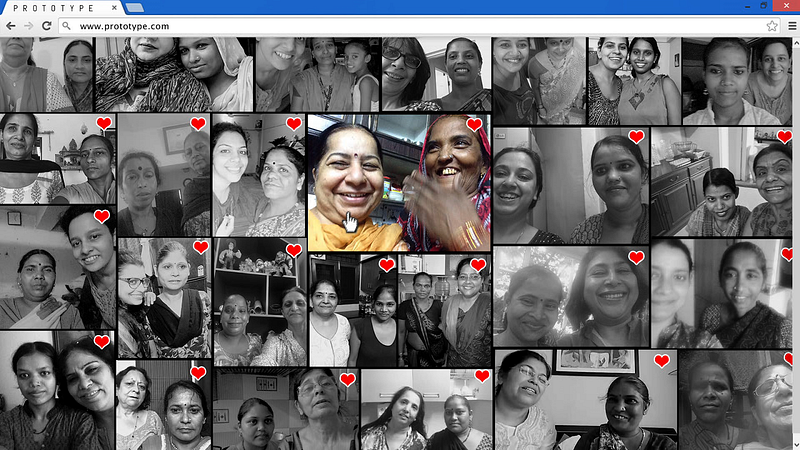

So where did I want to get to? I was seeking a film form that would enable me to curate more than direct the experiences and conversations that showcase how this multiverse shapes and is shaped by women. Since I was hoping to engage with women from socio-economic classes traditionally excluded from city narratives and screening spaces, an i-doc embodied the disruptive potential of bottom-up narratives and alternatives to theatre-based screenings.

A mobile phone based i-doc, therefore, seemed to be the perfect model to allow such a story to tell itself. The working title for this project still in process is Baatcheet (Conversations/Dialogue).

Irrespective of the medium, an i-doc can be conceived of as a jigsaw puzzle whose individual pieces—when combined and re-combined—present a different but engaging image. Interactivity is thus manifest in intellectual and emotional navigation of the filmic material.

In this case, it mirrors the physical act of traversing the city and exploring its sights, sounds and people. Exploring diverse points of view and reimagining the city through self-chosen paths also empowers audiences to get involved as co-creators of the film.

In his travelogue City of Djinns (1993), historian and author William Dalrymple writes that the city has “…a bottomless seam of stories.” The form even helped address my discomfort with being the sole chronicler of a city that transforms itself even before one finishes describing it!

i-docs:

Windows to new worlds

i-docs:

Windows to new worldsIn the course of my collaboration with domestic workers and homemakers I have experienced the political and personal pleasure of this reduced directorial role. The agreed framework of filming what-you-want and how-you-like-it revealed a far more expansive vocabulary about the city than was accessible to me. Joint reflections on assumptions that are made about women — their work, choices, behaviors and perceptions of the city—point to the transformative potential of i-docs. I have seen the tale re-invent the teller herself.

In one of the mobile phone recordings that will form the completed film, Nirmala, a domestic worker, is poker-faced as she tells her employer Shaheena, “One felt unsafe [after the rape]. The city suddenly seemed dangerous.”

As Shaheena nods in agreement, Nirmala cannot help but break into a smile. “So, we decided to venture out in twos and resolved that if any man harassed us we’d simply round him up and thrash him with our slippers. We were prepared.” Shaheena can’t hold back her laughter, either. They grin with a conspiratorial air. I grin back at the screen each time too. My takeaway isn’t the risk the city poses, but the chutzpah these women have to take it on.

Will my “‘viewers” think the same? Imagining a model viewer/user and designing their journey through the conversations and other footage is a daunting but exciting task. As I think through the possibilities and review the footage I am reminded that conversations can go anywhere. Perhaps that is the quintessential experience of the i-doc — I don’t tell people where they ought to go. It depends a good deal on where they want to get to.

Anandana Kapur is an award-winning filmmaker and co-founder of Cinemad, India. Previously an executive producer for non-fiction programming on TV, she has worked on information and video campaigns for the Government Of India and UNICEF. Anandana also teaches courses on Documentary Practice, Community Activism and Researching Media & Culture and her published work is on gender and film studies. A recipient of the Fulbright-Nehru Fellowship as well as the Shastri Indo Canadian Fellowship Anandana is currently pursuing practice-based research on the interactive documentary genre.

Anandana is at the Open Doc Lab at MIT this fall and is looking for programmers to collaborate with on this project. She can be emailed on anandana@mit.edu.

This piece appears in issue #10 of Immerse, which was curated by the editors of i-Docs: The Evolving Practices of Interactive Documentary (Columbia University Press, 2017). Discover other stories in this issue here.

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.