5 lessons from “new media” during the 1918 waves of Influenza and racial terror

History may not repeat, but it can rhyme. At Immerse today, we are concerned with emergent tech and media creation in the context of Covid-19 as well as the global uprisings against state-sanctioned racial terror. History might help reveal the connections between technology, art, pandemics and racial injustice. What rhymes do we hear?

- State and media players name the virus to define the narrative

A hundred years ago, a pandemic misnamed the “Spanish Flu” killed 50–100 million people around the world between 1918–20. The influenza or “grip” was mis-associated with Spain, because it was the first country to actively publicly report on the pandemic, while wartime censorship laws everywhere else stopped the news. State media control in the US, Europe and elsewhere covered up — and contributed to — the global health catastrophe, as it was deemed unpatriotic and dangerous to report on the flu during World War I.

<So too, in 2020, refractions of a misnamed flu resonate loudly in rationalizations of anti-Asian racism and violence across the world, along with delayed and confused state responses to the pandemic.>

2. Pandemics create vacuums for media conglomerate takeovers

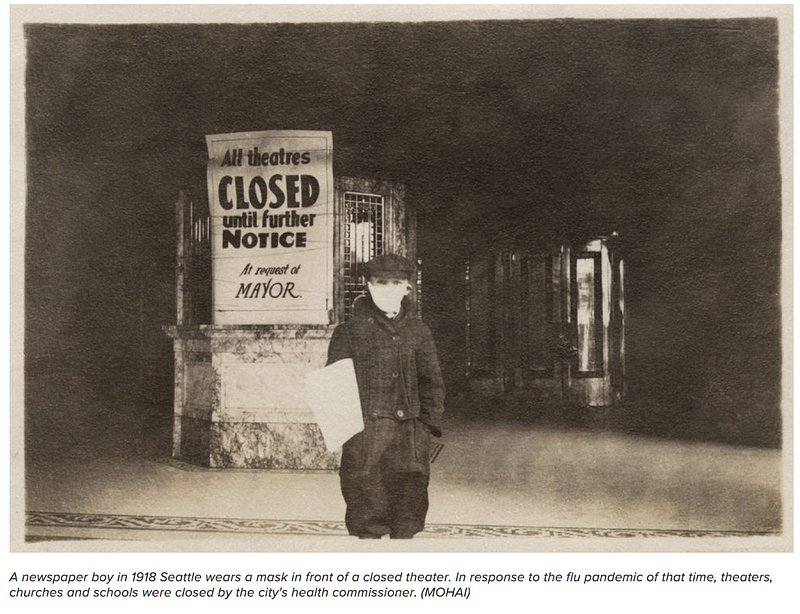

The second deadliest wave of the flu hit in Fall 1918, and cities across North America shut down. In most cities, theatres, cinemas, bowling alleys, churches, and pool halls all closed. Across the continent, 80–90% of movie houses closed for 2–6 months. It was the height of silent cinema, and most studio production was also halted for months. Meanwhile, a Hollywood mogul named Adolph Zukor, co-founder of Paramount Pictures, used the pandemic to buy out the beleaguered mom and pop theatres across the country to create a new monolithic vertically integrated studio distribution system that would dominate 20th century cinema.

<In 2020, as film festivals, cinemas, exhibition spaces vanquish in lockdown, how are the infrastructure companies such as Amazon, Facebook, and other platforms profiting from and dominating the media landscape?>

3. Artists get sick too

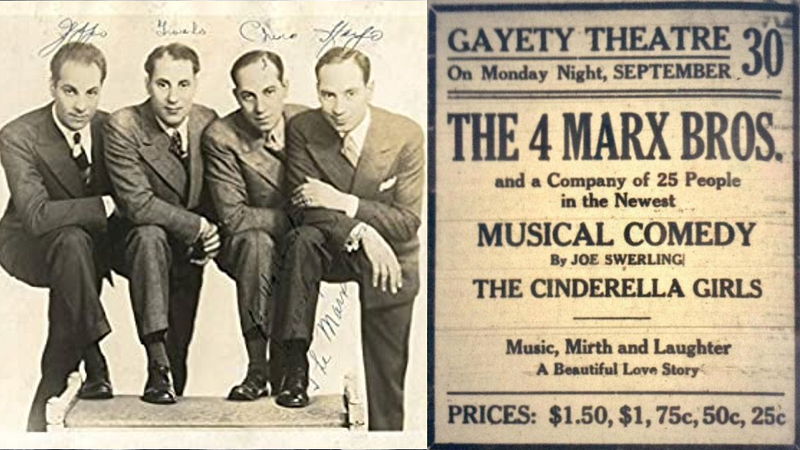

What about the artists? Mary Pickford and many silent stars fell ill during the 1918 pandemic. Pickford survived the flu. So did a child named Walt Disney. The Marx Brothers were already famous but still touring vaudeville when their own show, “The Cinderella Girls” (which they themselves described as a flop) shut down. The brothers retreated and quarantined on the family farm in Illinois but Groucho got sick.

When quarantine was lifted, very few of the artists depicted the social circumstances or their own personal health trauma in the work. There is one rare scene in a 1919 Pickford picture at a train station in which a sneeze sends bypassers running for cover.

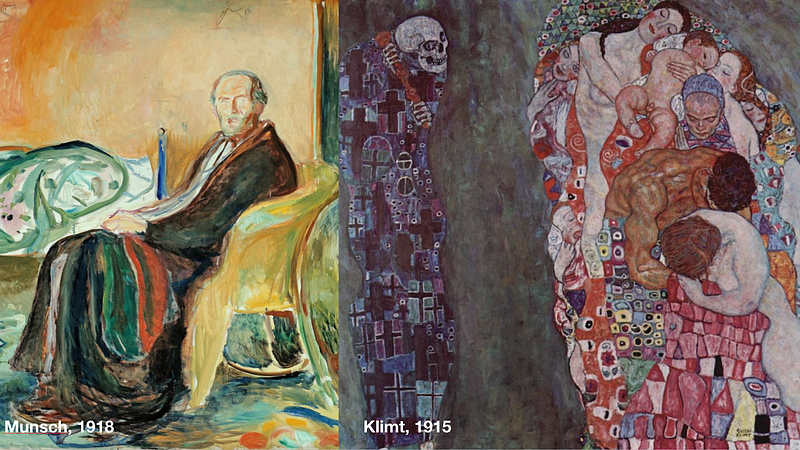

Painters in Europe, on the other hand, such as Munsch and Klimt confronted Influenza in life and in their work. Klimt succumbed to it. Franz Kafka too, contracted it but survived. His writings epitomize some of the period’s most eloquent existential reflections on illness, both individual and collective.

<How will artists in 2020 experience and depict Covid? Or is it something to be quickly forgotten?>

4. Documentary and social media can be foggy, ephemeral

Of course, in 1918, documentary film was only nascent, barely an emergent new media, in the form of newsreels, which were popular and ran in cinema houses but were focused on the war efforts and “the “everyday.” In most countries, newsreel producers would have been adhering to strict wartime censorship, and the flu went largely visually undocumented in moving images. Flu news reporting was confined to print and some photography, and often buried in back pages. Radio was not a mass medium yet.

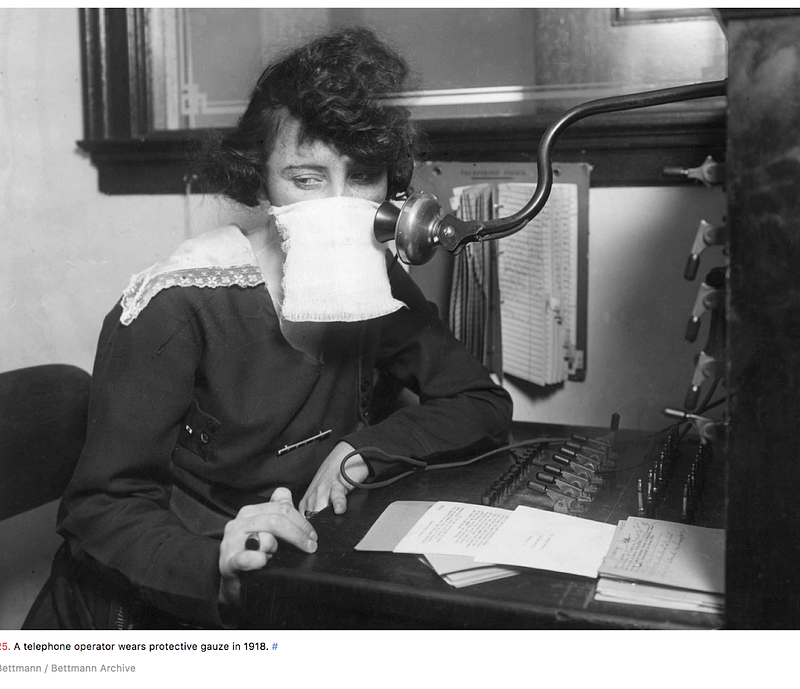

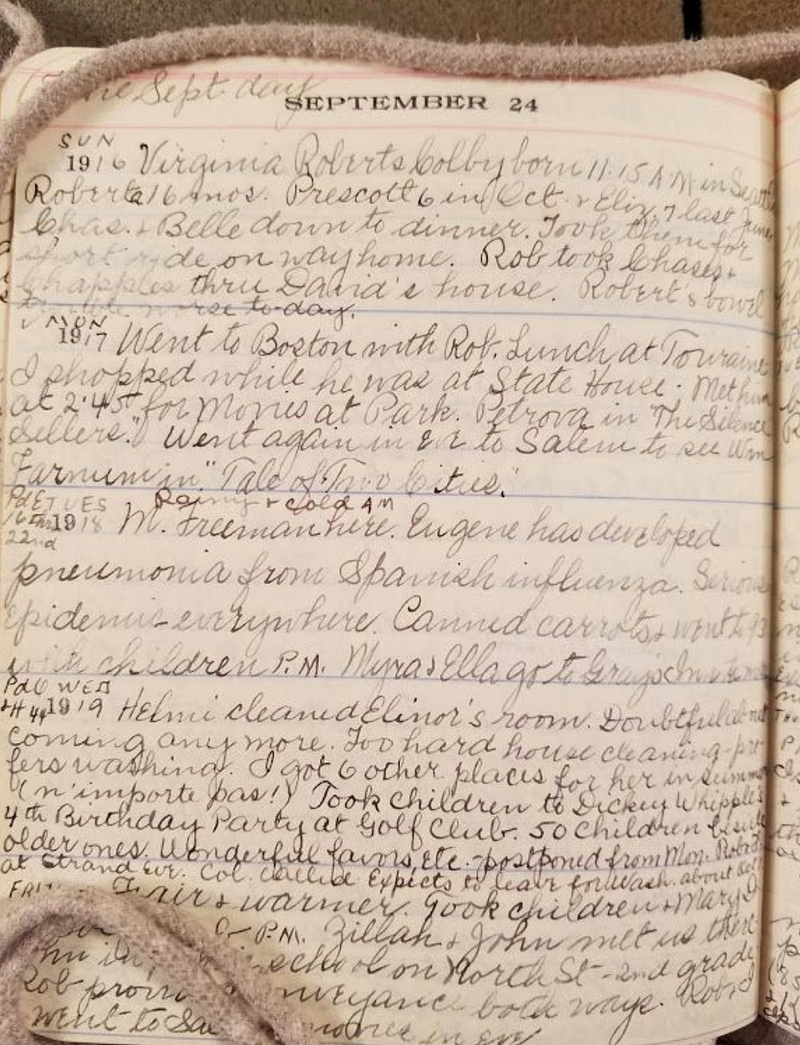

Meanwhile, the emergent tech of the time was the telephone. The tech was far from ubiquitous, only about a third of American households had one in 1918. Companies first promoted them, but later begged users to limit phone use because so many operators had fallen sick or victim to the disease. What news was whispered across the telephone lines in those stolen minutes? Little documentation exists. Journaling and letter-writing give us some clue. First-person, handwritten accounts portray some of the texture of individual illness and reflections on neighbourhoods and everyday life during the pandemic.

The tech was already shaping new contours of an extended peer-to-peer communication model. A proto-social media.

<In 2020, information and data floods across news channels and social media platforms, yet meaning making and deeper understanding is frequently lost. The epistemological crises are profound. How do we know what we know? What and who can we trust? How are we limited in our meaning making today, and who benefits in the fog of mis/disinformation? As business models collapse, what will happen to the documentary form in 2020?>

5. Waves of pandemics, waves of racial terror

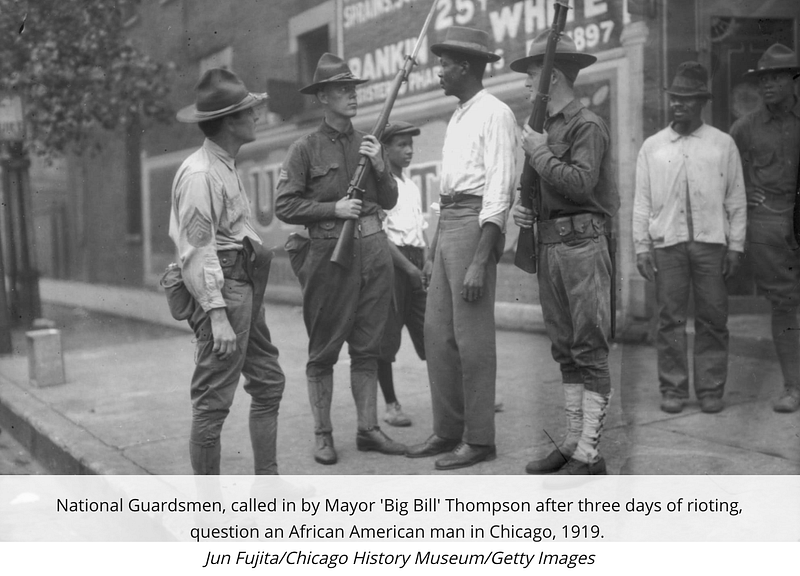

1918–19 was marked not only by the influenza but also waves of brutal racial terror in the US and uprisings to confront systemic violence. It was dubbed the Red Summer of 1919. In the south, the white supremacist Ku Klux Klan organization was responsible for at least 64 lynchings in 1918 and 83 in 1919. In the summer of 1919, uprisings would mount in Washington, D.C.; Knoxville, Tennessee; Longview, Texas; Phillips County, Arkansas; Omaha, Nebraska and, most dramatically, Chicago, where a week of conflict on the south side resulted in deaths, injuries and the torching of the homes of over 1,000 Black families. It was a crucial chapter in the movement to confront racial and systemic injustice in the US.

Over 100 years ago, users of new and old forms of communication tech were both constrained by a pandemic and propelled by it. So too, struggles over the pandemic narrative, the platforms and the messages aligned with millions of deaths, and a transformed media landscape. These struggles were connected to brutal expressions of violence to uphold white supremacy, and uprisings to challenge them.

What rhymes do we hear?

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.