My Wampum

bead in VR: Wampum was an antecedent to blockchain technology, which used story as part of its

structure.

My Wampum

bead in VR: Wampum was an antecedent to blockchain technology, which used story as part of its

structure.Every month, 55 million people play Minecraft, often hosting customized versions of collaborative worlds on their own home computers. The rules, formats, stories, and “mods” that these communities create are invite-only, and if you are lucky enough to receive an invitation, you will likely be talking, chatting, trolling with them on Discord, along with 130 million other users. If you want to learn the stories from these communities you can watch them live on Twitch, where a million people are watching at any given point in time. There are millions of stories created by collectives, hordes, bands, tribes, teams and pods that you may never know about or be able to follow. There are 1.8 billion gamers around the world who are probably ok with that.

These new formats are popular because they meet a deep psychological need: the basic human drive to interact with other people through stories. I call this new way of telling stories “decentralized storytelling.”

Decentralized storytelling only seems new. Although these forms make use of 21st century technologies, many of these techniques have a precedent in much older storytelling traditions. My thinking on this method for communicating through time is heavily informed by my native tradition (I am Seneca-Cayuga, Haudenosaunee, a “‘Native New Yorker” lol). My community has practiced decentralized storytelling for generations.

To those of us schooled in 20th century forms of storytelling — writing, film, radio, television — these new decentralized forms may not be recognizable as stories at all. Unlike publishing, radio, film, and television, which broadcast from a single source to an audience of many, decentralized storytelling networks are peer-to-peer; they emerge from the collective space of audience participation.

Communities organize around collective stories.

Decentralized storytelling requires navigating your human experience within a story-space. The architects of the story-space were your ancestors; it is a place in which your great-great-great-great-great-grandchildren will be born. It is a mind space, a physical space, and, for some, a game. It is a process of making and unmaking that cannot be sustained except in collaboration with the past and future, securing a connection with those living seven generations from now, listening to their experiences, and making stories that will be able to reach them where they are.

Decentralized storytelling requires navigating your human experience within a story-space.

In what follows, I will try to give you a map of the story-space. You can look at this map while you are strolling through the 21st century landscape, so you will know when you have stumbled upon one.

How can you tell if you are in a decentralized story-space?

Can it be embodied in multiple media?

One good indication you’re dealing with a decentralized narrative is that it’s distributed across multiple media. Consider big mainstream franchises like X-Men or Star Wars, for which there are movies, comics, novelizations, video games, and toys. Each entry to these fictional universes introduces new elements that push the narrative in different directions and force the canon to expand.

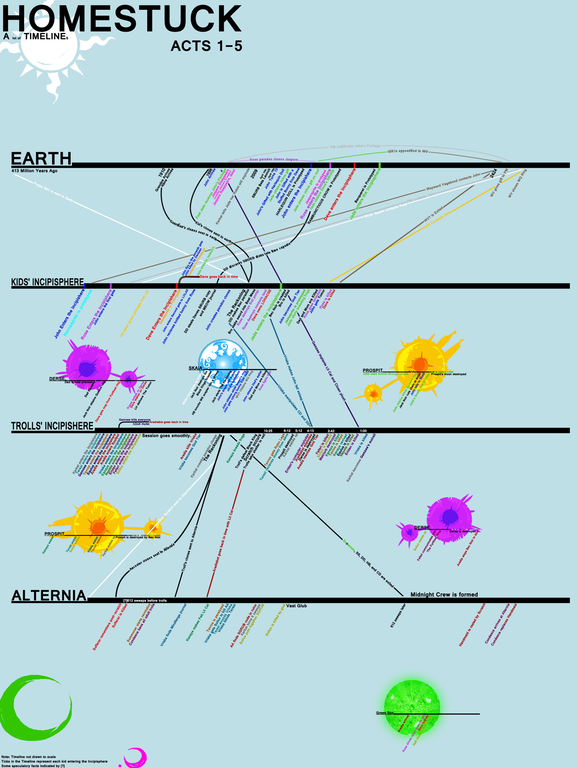

A

Timeline of Homestuck from A1 to A5

A

Timeline of Homestuck from A1 to A5Of course, these stories still fall under the jurisdiction of their corporate custodians. A more decentralized story-space might be the Homestuck universe, the sprawling, 8,000-page saga about “a boy and his friends and a game they play together.” It began as a webcomic but has also been developed in animated videos, and a game. When he created the series, Andrew Husse made everything in MS Paint — easy-to-use software that ships with Windows — and drew the characters in a rudimentary fashion. This made it easy for fans to replicate the characters on their own computers, and the Homestuck world flourishes as fanfic. With its multiverses and alternate timelines, the material that fans generate can be incorporated back into the canon (even the chat logs on Husse’s MS Paint Adventures is considered canon). It promotes radical inclusivity on every level; fans don’t feel like they need permission to enter into it and interact.

Does it take a long time to tell?

Next time you meet a Homestuck fan, ask them to summarize the story. If you’re not met with dismissive laughter, odds are you are in for several hours of confusion as they try to relate a profoundly convoluted plot that is still being written.

A decentralized story is open, which means there is a sense in which it is an ongoing performance, happening in real time. Not so with centralized stories; even those that take place in real time: Run Lola Run, My Dinner With Andre, and Dog Day Afternoon still take place in a scripted memory-space.

Decentralized stories happen in real time because they are mapped to real life. Following a news story on Twitter, for example, is a decentralized narrative unfolding in real-time (or something close to it.) In Twitch streams the audience watches a performer put on a show using the ready-made materials of a video game, all the while reading and responding to a live feed of comments from fans. Games such as Minecraft, VR Chat, or Eve Online for instance, don’t have any particular ends — they are just spaces in which people can come and act out stories for as long as they like.

Decentralized stories happen in real time because they are mapped to real life.

Does it involve a transparent system of transactions or trade?

Economies form in collective spaces when people define what they value as a group. In some communities the store of value is attribution and credit (as on Tumblr); in others it is the value of objects needed for trade within the story-space (in-game economies), or even MacGuffins that serve no function except to drive the story.

Economies are an indication that a community has not only defined values but also the means of interacting with one another via exchange. Each group has protocols in which to interact with others outside of their group. (This is one reason why economists are so fascinated with game theory — EVE Online even has its own dedicated economist to help the society created in that story-space.)

Does the story make use of existing features of its world?

Photo taken

at MCAD of Jonathan Herrera’s work and shared on Pinterest and Tumblr

Photo taken

at MCAD of Jonathan Herrera’s work and shared on Pinterest and TumblrA decentralized story gets its life from the people who participate in it. This is one reason that decentralization flourishes so well in the worlds of memes and fanfic — it’s easier to put on puppet shows with familiar characters than it is to create a whole new fictional universe from scratch. By using readymade features of an existing cultural landscape, and doing it on a platform that everyone can access, with tools that everyone has, decentralized stories make it possible for more people to participate in the telling of the story.

An advancement that is accessible to more people will last longer and be more influential than one that is not.

How can you tell if you are in a native story-space?

Can it be embodied in multiple media?

There are many ways of telling native stories. For the Haudenosaunee (aka Iroquois, or 6 nation: the Onondoga, Oneida, Cayuga, Seneca, Mohawk and Tuscarora) the process was shared across a variety of media. The stories were kept in multiple formats — they were incorporated into rattles, drums, baskets, pouches, metal pins, hair combs, wampum contracts, and spoken word. All this helped the storyteller and audience alike remember different aspects of the stories.

Corn Husk

Doll, Seneca, 1870s, from The

MET’s collection

Corn Husk

Doll, Seneca, 1870s, from The

MET’s collectionTake for example the story of why the cornhusk doll has no face. These dolls were made out of the Haudenosaunee staple corn — of which they had hundreds of colorful varieties — and were always made to be wearing beautiful outfits but never given a face.

The story goes that the community was harvesting their year’s worth of crops one summer, and got distracted soaking up lots of fun in the rare northeastern sun. They didn’t harvest as much as they should have, and when a cold snap hit, the terrified community prayed to the Creator for guidance. He sent them assistance in the form of what we now call “Indian Summer” — that strange time in late fall when New Yorkers suddenly find that they can go to Central Park in a bikini and have one last picnic with their friends.

Excited and rather desperate to get in those last few weeks’ worth of food, everyone in the community went to the farm to harvest — mothers, fathers, uncles, aunts, grandparents, teens, babies on their mother’s backs. In their haste they left the children to fend for themselves in the longhouses. The children soon got into tremendous trouble, and the Creator sent a messenger in the form of the wise old Owl to fly down and make their displeasure known.

“How have you left the most important thing in the community alone and without any sort of guidance or oversight?” asked Owl. “The children, the single most important thing, have been left to themselves and they are running around being crazy little kids. Please, guys, this is not in any way how you are supposed to behave.”

The parents threw up their arms and said, “If we don’t harvest, those children will starve in the winter, as will we.” Owl considered this, and flew back to tell the Creator.

Owl returned hours later with a beautiful woman made of corn, her hair made of corn silk and her beautiful skin made of corn husk.

“This is the Corn Husk Woman,” said Owl. “The Creator has given her life so that she may be a teacher and babysitter to your children so that you can do the important work of harvesting the food for the winter.”

The children were very happy to have an entertaining teacher to sing them songs, tell them stories, walk with them to the forest, take to the fields to play games and to the pond near their home. They all had a great time with her, she was super cool. But one day she passed by her own reflection in the pond she saw how beautiful she was. She sat down and began to brush her beautiful hair and sing with her beautiful voice, and became so totally absorbed in her own beauty she didn’t realize that the children had gone back the the village and were up to their typical shenanigans.

Owl returned the the fields very upset. “Dude, guys, wtf. We sent you a literal Corn Husk Woman to take care of your kids and they are still being holy terrors in the village!”

The parents were pretty shocked. When Owl saw the look on their faces he flew to find the Corn Husk Woman, and found her taking selfies near the pond.

“Wow, just wow,” Owl said. He told her how she had betrayed the most important job that is given to any creature: to care for children, to teach them, guide them, and watch out for them. He was so disappointed in Corn Husk Woman, he took away her face. She felt deeply ashamed and returned to the children and took good care of them until the warm period ended and the parents returned. Then she returned to the corn whence she came.

Now, if I asked what is the lesson in this story, what might you say? Vanity tears apart the fabric of society? Children are our greatest resource? Don’t be lazy? Well, it is all of these things. But more than anything, it is a way to teach a technology.

The story of the Corn Husk Woman was a way to teach a technology.

The Haudenosaunee had a very advanced farming infrastructure and were able to store and provide food over the very long winters for thousands of people in their cities. Teaching even the very young the concept of organized harvest and the calendar event “Indian Summer” helps them to remember this story for generations to come. The moral lessons are good, too, but it was their agricultural technologies that allowed them to survive the long, bitter New York winters.

Does it take a long time to tell?

The first time I heard the Haudenosaunee creation story was at the Strawberry Fest at Ganondagan, the site of the largest Haudenosaunee city until a war with the French forced them to abandon it. My mother was the manager of this historical site, and as a young storyteller apprentice she took her small children to listen to an elder who told the story. The story started on a hot summer Saturday at 11:00 am and the storyteller stopped in the beginning of the story at 6:00 pm, when we left for the day. It continued on the next day and until the Strawberry Festival ended.

The length of stories has everything to do with the way in which our society is organized. The Haudenosaunee traditionally lived in communal longhouses led by the matriarch of the family, where over 35 people would spend long, cold nights. Long, elaborate stories were something we could binge for a few hours a night over the season. Storytelling was an all-ages affair, and we needed to have exciting ways to reinforce our shared values and technological advances.

Does it involve a transparent system of transactions or trade?

The Haudenosaunee were traditionally a matrilineal, matriarchal, confederate democracy. We also had advanced forms of trade and transaction. One of our main economic instruments was wampum, which many people incorrectly believed to be money. It was used as a unit of exchange, but its main function was much more similar to modern-day blockchain — a complex negotiated treaty or contract in a public ledger recording agreements governed by individuals, nation states, and nations. Explaining the Haudenosaunee wampum, a Jesuit missionary in 1645 wrote that the purpose of wampum holds “the same function as writing and contracts among us.”

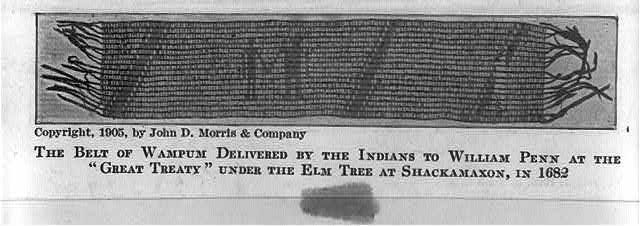

Totally one of the first

friendship emojis, how cute is this? (from Wikipedia)

Totally one of the first

friendship emojis, how cute is this? (from Wikipedia)This is partially correct. Wampum was a contract, but it was inseparable from the oratory structure of negotiating contracts, which was also meant to protect and communicate the shared values of your community. It was a record of an agreement that had been reached through the process of storytelling as communication. Wampum is a process of encoding abstract agreements — stories are literally woven into the material.

Wampum is a process of encoding abstract agreements.

The most famous patterns are still created to tell of our clans, our confederacy, and the thing that is most important to the Haudenosaunee: the great law of peace, which made our peaceful democracy possible.

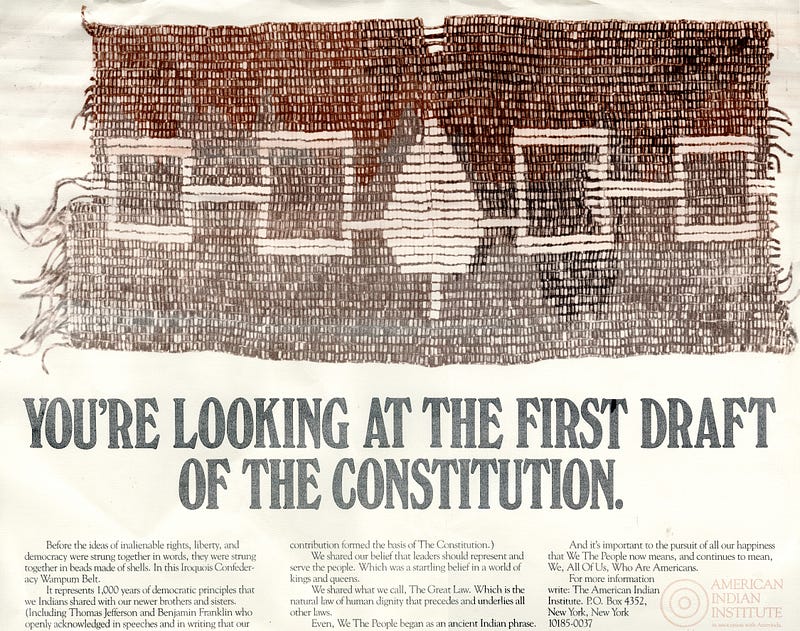

1,000 years

of democratic principles in Wampum inspired Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin’s drafting of the

U.S. Constitution

1,000 years

of democratic principles in Wampum inspired Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin’s drafting of the

U.S. ConstitutionDoes the story make use of existing features of its world?

When a child asks, “What about that river? That mountain? That lake?” it is natural to tell them a story. Stories are entertaining, they teach about your collective values, and they provide knowledge that will save that child’s life one day.

Using basket patterns, wampum, songs and stories are ways for the community to remember — they are techniques of decentralizing information, embedding the same story in multiple formats. This was a way of ensuring that the most important knowledge of our communities would be accessible to everyone. Telling by weaving a lesson about technology, medicine, or values in with the story of how a rock formation or a river path was formed helps people remember the story and cements those relationships in people’s minds.

Can the story last for seven generations?

Skawennati (Mohawk) has been using gaming engines to tell complex stories that move forward and backwards in time. Wendy Red Star’s (Apsáalooke) Thunder Up Above series are fantasy space sagas with handmade wearable celestial bodies. I tell stories using the internet, code, VR, AR, and Interactive Performance art using decentralized methods.

There are many of us who are working from our cultural traditions and using technologies that fit the needs of our communities. Wendy and I are working on a new 360 video project using our respective cultural stories about monsters as inspiration.

Why do we embed our stories in the landscape, in toys, dances, or songs? We believe that every action that you make will have an effect for seven generations. If you are careless or cruel it will cause a scar of trauma that will last through the next seven generations as well. If you want to teach something, you must teach it in a way that would last for seven generations.

We teach with stories, and so our stories need to last, to be understood for seven generations. When you understand that then you will know why our way of telling stories — which you might call “decentralized” — makes a whole lot of sense.

We teach with stories, and so our stories need to last.

I approach decentralized storytelling in a Haudenosaunee way: Our current world is the result of seven generations before me. I am interacting with the world designed by my ancestors and yours. My life is a way to communicate with the people born in the future seven generations from now.

Today the stories we tell are embedded in networks and pixels instead of wampum and rivers, but they may still have the power to last through seven generations, to influence the lives of my great-great-great-great-great-great grandchildren, for the people I do not yet know, and those I have only met in dreams.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and is fiscally sponsored by IFP. Learn more about our vision for the project here.