Immerse issue #8: On what makes for good VR

Ready to

have your neurons restyled? Have a seat in the NeuroSpeculative

AfroFeminism VR installation.

Ready to

have your neurons restyled? Have a seat in the NeuroSpeculative

AfroFeminism VR installation.This month’s reads aim to grapple with VR’s biggest promises, stressing the need to refocus efforts on content and imagination. They’re curated by Sandra Rodriguez, whose work focuses on exploring interactive and immersive approaches to non-fiction.

As young as they may be, the production and consumption fields of VR are constantly shifting. Public and private funders, such as the author of this month’s feature, Diana Barrett of the Fledgling Fund, might be piqued by the outreach and storytelling potentials of this new platform. But how do they choose which VR projects to support? Should they encourage innovation in form? In platform? Should they push for story? Or finance experiences that add to a variety of tools, grammars and modes of expressing human experiences?

Here are a few resources and observations that might help.

Relevant, compelling, accessible content

VR headsets change and evolve, so does content. In the last three years, we’ve seen different types of VR formats emerge, adapting to burgeoning platforms. These range from 360 videos and “rollercoaster rides” that can be viewed in “magic window” mode (on a mobile phone, a cardboard viewer or on a laptop), to 360 location-based aesthetic videos (see Felix and Paul studios), to rapidly shot and stitched narratives that focus on newsworthy stories. A fantastic example of this last genre are the immersive videos produced daily by the New York Times.

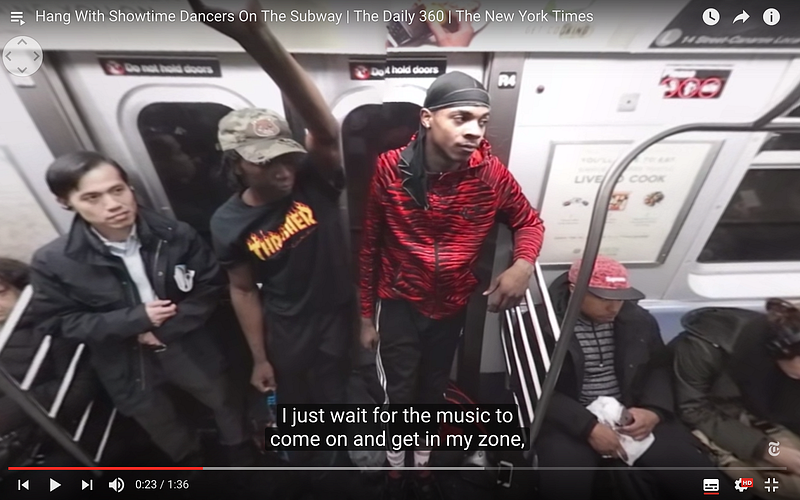

A

360 video from the New York Times Daily 360 invites us to hang with the NYC Subway Showtime

Dancers.

A

360 video from the New York Times Daily 360 invites us to hang with the NYC Subway Showtime

Dancers.To ensure impact, sound and image quality has been a struggle — particularly for 360 videos that can’t seem to live up to the promised sense of immersion because of how pixelated and deformed they still are. Makers (such as Felix and Paul) have been investing heavily in developing proprietary technology that enhances visual quality, image and sound definition for stereoscopic 3D contents.

The results are interesting — more comfortable teleportations of oneself in remote locations, circus tents (see Ka Cirque du Soleil, available on Oculus), real live-recorded singers (Hallelujah by With.in) or beautiful undersea worlds (the Click Effect).

Yet, as many funders of non-fiction stories already know, public engagement is not just a question of image definition. It relies heavily on the originality and relevance of available content. This is actually one of the hardest lessons learned by VR top industry leaders. No matter how much they invest in platforms and headsets, the VR hype always hits its trough of disillusionment. If the content and UX design are technically fantastic but not relevant, the public/users/visitors/consumers won’t return.

This lesson should be a driving force for funders — there has never been clearer demand for human centered, relevant non-fiction content.

The second biggest blind spot for providing meaningful and impactful VR content is accessibility. To have impact that’s real, social, and felt, immersive content needs to be made available to more than just a few selected festival goers — no matter how much journalists t0ut a VR piece.

To address this issue, WebVR might still be glitchy for many, but it might also save us all. It is currently the best way to ensure VR projects can be accessed through as many formats as possible (VR headsets, mobile phones, laptops). Here is Brian Chirls of Datavized on WebVR in an MIT Lecture we curated for the Hacking VR lecture series that’s featured elsewhere in this issue:

Brian Chirls — Hacking

VR Lecture Series

Brian Chirls — Hacking

VR Lecture SeriesWhat is real?

Another important lesson for documentary VR funders is that “non-fiction” doesn’t necessarily mean “live capture.” The interest shown in creative projects that focus on what “feels real” rather than what “looks real” should inspire.

One can here think of interactive and CGI (Computer Generated) projects such as The Guardian’s 6X9, the popular and beautifully crafted Notes on Blindness, or even interactive and game-like reflexive experiences such as NFB’s Cardboard Crash (also check out Vincent McCurley & NFB’s latest VR project on North America’s first legal supervised drug injection site.)

And what about tougher-to-visualize subjects? See Scatter’s Zero Day VR, where you’re invited to embody a cyber virus in a worldwide computer war.

The overall message here is that human imagination should not be bound to making us feel like we’re walking in someone else’s shoes. That’s too easy in my perspective.

Human understanding is above all felt. It is driven by words, poetry and our unbound imagination.

An interesting read on this perspective is Claire Evans’ August 2016 article: “On Virtual Reality: Forget Real-looking. Let’s try for Real Feeling.”

For more on how reality can be represented differently across VR thinkers and makers, here is MIT Open Documentary Lab’s May 2016 report: Virtually There: Documentary Meets Virtual Reality.

And let’s hear it from the Godmother of VR herself, Nonny De La Peña and her colleagues. “Immersive Journalism: Immersive Virtual Reality for the First Person Experience of News.”

Whose reality?

Finally, in thinking about which VR projects to support, funders should remember that accessibility doesn’t just mean being able to access VR content. It should also mean making sure production is in reach for a widest diversity of creators.

Who gets to tell stories in this new field will, after all, define its parameters — the types of immersive stories, styles and languages that we’ll develop over the following decade.

Many like to underline the fact that VR needs to be conceived as an ecosystem. Well, as I have noted in all of my public talks recently, if you remember your high school biology class, you remember that “any ecosystem needs diversity to thrive.”

VR is not as new as it seems. For creators who were pushing the field back in the 1990s — in particular, women, indigenous artists, and other minority groups — the new hype of VR is simply history repeating itself. Yes, there is the promise of breaking a glass ceiling by creating freely in a nascent medium. But the funding, the media coverage, and of course the attention, still seem to focus on whomever the tech industry has taught us to listen to — not what innovation really means.

Thinking about these issues should be baked into the very code of VR experiences. T.L. Taylor, professor at MIT Comparative Media Studies and Game Studies Sociologist, was one of the 1990s VR fans. Here is her reminder about representing embodied selves in virtual worlds (may they be VR or computer games).

Many other interesting initiatives are out there in VR and we don’t hear about them enough — see, for example, the Afripedia project. What about rethinking afro-feminist futures through cyberpunk beauty salons? Or, as adrienne maree brown stated in another edition of Immerse, “Now is the Time for Visionary Narratives.”

The VR projects that wow us, the ones we return to and the immersive experiences from which we truly learn, are rarely the ones covered by tech media innovation gurus. But they stick with us. Because they tap into something much more important than high definition — they call upon our capacity for imagination, for feelings and for human relations.

Human-Centered Design

One last note. Creating compelling VR experiences is hard enough. It can quickly become gimmicky, if not purely nauseating, when all efforts are put into the bling and not enough into how VR projects are actually perceived and physically experienced by a… human.

Here is a fantastic book on Human-Centered design for Virtual Reality — just to make sure that while we think about all of the imagination, content and ethical issues that are paramount to creating a super VR piece, we don’t actually forget about making sure that the experience is compelling, and that you won’t need a bucket after viewing it.

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.