A response to the Making a New Reality series

Creating

ripples in every direction

Creating

ripples in every direction“How can we break the models of social good that perpetuate superiority and inferiority complexes and therefore cause us to miss so much value?”

This is the question asked in “Democratize Design” from the Making a New Reality research project. This piece goes in depth about strategies for collaborative design that are focused on the active participation of members of society and communities that have been traditionally marginalised. I want to add to this by addressing what designers and developers who are creating new media can be doing right now, even if they don’t have the resources that can connect them to a multitude of perspectives. Building on the concepts discussed in both “Democratize Design” and my previous piece “Embodiment and the Boundaries Between Us in Virtual Reality,” this article aims to construct a framework that can function as a catalyst for perspective shifting and reveal implicit biases in the design of human representation.

“Social reality is lived social relations, our most important political construction, a world changing fiction.”

This quote from Donna Haraway’s seminal essay “A Cyborg Manifesto” preceded my previous article and I want to draw attention to it again as it effectively sums up the nature of social reality in relation to media design. This sentiment is echoed in “Democratize Design,” which discusses a strategic design approach to empower marginalised voices through envisioning potential future worlds know as World Building:

“World Building designates a narrative practice in which the design of a world precedes the telling of a story … World Building is founded on three beliefs, namely that storytelling is the most powerful system for the advancement of human capability due to its ability to allow human imagination to precede the realization of thought; that all stories emerge logically and intuitively from the worlds that create them; and that new technologies powerfully enable us to sculpt the imagination into existence.” — Alex McDowell, Director of The World Building Institute

If we think about of our individual stories in the current world, to some degree we have been conditioned to perform within the boundaries of dominant discourses that define the reality in which we live; a reality which is largely designed through media representations and their continued reiterations.

“Discourses” can be thought of as narratives that adhere to certain ways of viewing and being in the world, which aren’t necessarily conscious but rather embedded as “common sense” in a community’s understanding of human experience. It is discourse that creates and/or maintains specific social power relations between different groups of people and once you learn to look for it in media representation, it becomes apparent. It is akin to learning how to read the “source code” that generates subconscious conditions of human relations.

I have previously used the theory of “Agential realism,” which is rooted in physics’ notion of entanglement to reveal power relations in media discourse, and, while I won’t go into the details of this theory in this article, I will borrow a few points that are valuable for designers and developers to use in understanding the discourses being channeled through their work.

- “Accountability and responsibility must be thought of in terms of what matters and what is excluded from mattering” (Barad, 2007, p 392).

- The nature of materiality itself is an entanglement that always demands an “other” (p 392). In the example of able-bodied and disabled individuals; both of these types of embodiment depend on the other for their very definition and hence existence (p 158). The same can be said for any type of othering: people of colour and white people, women and men, homosexual and heterosexual, etc. The very definition of these labels relies on their others for meaning and for a power-relation to exist in the first place. Inhabiting a combination of these labels develops identity and our performance towards each other through our identities is responsible for generating the power balances of our relations.

- “Differentiating should not be a process of othering or separating, but on the contrary about making connections and commitments” (p 392).

So how can we understand these points in relation to designing for inclusivity?

- We must reflect on our design choices and ask: “What matters and what is excluded from mattering?” and question ourselves as to why this is the case. Taking responsibility for our work is all about our ability to respond to other perspectives.

- Our own existence and identity is connected to everyone else’s and the ways in which identities are portrayed in media influence the power dynamics of how we come to understand ourselves and perform in relation to each other.

- The understanding that our identity is fundamentally reliant on others to exist should be the basis of developing a design practice that makes connection the focus instead of separation.

To illustrate these points, I will present a couple of examples of contemporary design in virtual reality that are unintentionally still perpetuating the marginalisation of Non-European people, in spite of good intentions. While it is clear that media is sometimes designed for specific audiences, I have chosen these two examples because of their intention to connect with a wide audience.

The colonisation of imagination

Wonderful You VR is an impressive experience that takes the viewer right into the womb to witness the development of the five senses of a foetus from conception to 35 weeks. It invites the audience to “meet your unborn self,” and seeks to portray the wonder of human development through viewers actively imagining themselves as the developing foetus. This is also helped by narration that explains how “your” body is growing. The elements of immersive imagery, sound, music, and narration flow together showcasing virtual reality’s unique ability to envelop the viewer, creating a captivating and visceral storytelling experience that also serves an educational purpose. But…

The

35-week-old model of a baby in the womb

The

35-week-old model of a baby in the wombAs we have become so accustomed to when looking at media and in particular educational depictions of humans there is once again a standard model used to portray the wonder of human development. It’s not in the least surprising that the standard we are presented with is of European appearance; in fact, it is a given. While this VR experience is based on cutting-edge science, if we for a moment assume the role of designer, let us ask the question: what matters and what is excluded from mattering in this experience?

In regards to a factual medical representation of non-European babies in the womb, it is not a question of clear skin tone differences, due to melanin mainly kicking in after birth. However, other options of human appearance are nevertheless excluded. This chosen “norm” is a familiar one used over and over in media, and whether consciously or not, it is actually based on members of society considered to be a socio-economic priority.

A model of a 35-week-old human baby could easily be represented with different features such as thicker lips, broader nostrils, Asiatic eye shape, dark eyes or a full head of hair. If this model were represented in another way, would it be considered too exclusionary to expect white audiences to use their imagination as prescribed by the marketing tag to “meet your unborn self”? Or does it always have to be Non-European people that are called on to develop and then continuously use an aspirational imagination in order to see an image of themselves in a white body?

And while this major design choice may be an unconscious one that just follows the “common sense” of a historically recognized “norm”, the discourse defined by this choice is ironically further pushed in the marketing campaign under the guise of diversity. The marketing of Wonderful You VR includes a video of people of diverse appearance experiencing and then describing their thoughts about the importance of this VR work. The specific use of these people is a central device for prescribing the “normality” of the baby’s singular representation. This works to nullify any thoughts of exclusion while still maintaining the underlying narrative of what type of human is more important in society. By once again asking the question, “What matters and what is excluded from mattering?” we can see the colonisation of imagination at work.

Design cannot continue to remain a zero-sum game, where in order for a human to be represented, some people are recognised while others are not. The work of new media creators has the potential to be widely distributed across many countries and, given the increasingly diverse makeup of contemporary societies, we cannot meaningfully “speak” to a wide audience by only representing a certain group. While establishing a “standard” or “norm” is the easiest option technically, it is always going to leave many behind, therefore also creating a narrative of social relation. As creators we must put more energy into thinking laterally given the multitude of new design possibilities available through ever emerging technology. Inclusive representation matters, and it should no longer be considered an impossible task.

A story of social relation

My second example shows just how deeply embedded dominant discourses are in our psyches and how they can continue to function even in the case of seemingly inclusive design.

AltspaceVR is a pioneering social space in virtual reality. Its tagline is “be there together” and it offers both human and robot avatars for people to inhabit. AltspaceVR describes itself as having a “whimsical” visual style and as such the avatars follow this light-hearted approach to representation.

The human avatar line is simple and presents users with a standard male and female model whose skin tone, hair colour and outfits can be changed according to the user’s preference. However, these are the only things that users can change within the frame of a standard model that closely follows socio-historical preferences of the western world, i.e. slim body types, women with straight hair and child-like features. My previous article goes further into a critical analysis of AltspaceVR’s human avatars, but in this article, I would like to focus specifically on the layout of their avatar selection menu. This menu follows an exclusive “common sense” that designers can easily perpetuate without realising.

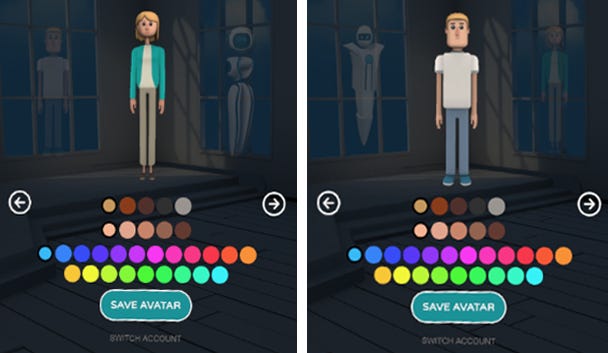

The human

avatar selection menus in AltspaceVR at the time of writing this article

The human

avatar selection menus in AltspaceVR at the time of writing this articleThe first thing one notices when looking at AltspaceVR’s human avatar selection menu is that as well as a standard model of human there is also a default of skin tone and hair colour. So, what matters and what is excluded from mattering in this case? The underlying narrative of having a default is the assumption of what is normal. Considering that AltspaceVR is a virtual social space where people from around world can “be there together,” would it be so strange to imagine the default model having brown skin and black hair?

Once again, we find that this is actually zero-sum identity territory. Despite the identity choices presented, the layout further instills a hierarchy and subsequently a narrative of who is the more important. While this may be a visual “common sense” of neatly positioning colours from light to dark, it would also be just as neat in a dark to light order. The hair colour menu is interesting because as well as laying out colours from light to dark it also positions the grey hair option right at the end. If it went by true light to dark logic then grey would actually be in the first position. The apparent visual rationality of this ordered presentation clearly makes room for disruption, so that it can also fit within a broader logic concerning the relevance of older people in social environments.

Humans learn to understand the world through order, so while these design choices may seem harmless at first, our brains function to draw connections about reality through orders presented. And when specific orders are repeated continuously everywhere in the media they eventually become an unquestioning “common sense.”

Addressing the elephant in the room

In both of the above examples, despite creators being inclusive-minded the reiteration of certain design “common senses” continues to preserve the very boundaries that are trying to be broken. This article is not about making a negative case against certain creators; rather, it is about revealing how easily we can all be complicit in perpetuating a divisive and hierarchical story of being human without even realising.

To combat this, here are some key points that designers and developers can use in addressing unconscious issues of exclusion in human representation:

- Asking the question, “What matters and what is excluded from mattering?” during your design process is a useful tool, as it can help to reveal socially conditioned biases that are hiding in plain sight.

- Make a list of the inclusions and exclusions in your work and write down the reasons for them. Think about the logic behind them.

- Where exclusions seem inevitable due to deadlines, budget, or technical limitations discuss them openly in regards to what kind of social hierarchy they may be promoting. Don’t just pretend they don’t exist.

- Think about your use of inclusive language when marketing your work and whether this accurately describes what your design offers. Glossing over issues only adds to the problem of exclusion in society.

Having the courage to disclose uncomfortable truths and have discussions openly can create new spaces for inventive thinking. If enough creators take part in openly deconstructing their work, a cultural shift can take place—hence, making united awareness and effort in solving social representation a key feature of new media design culture.

Connection through design

Developing a design practice of representation based on connection rather than separation can also begin with focusing on the affordances that new media bring, which can help clear the historical “common senses” of order maintained by 2D design.

In the case of virtual reality, users have the potential to both view and handle 3D objects, which creates new scope for interactive interfaces allowing the concept of “selection” to be free of specific arrangements. For example, one idea could connect skin colour selection directly to 3D colour visualization. Visualizing colour in a non-hierarchical way has long been part of computer science and the film and television post-production toolset, and VR has the ability to adopt this concept in a unique way to make a tangible non-hierarchical ‘selection’ experience.

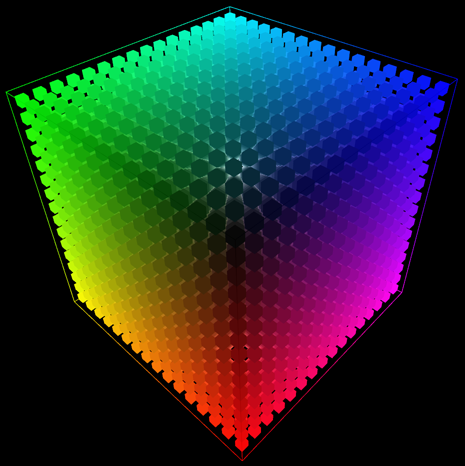

An example

of 3D colour visualization. Source

An example

of 3D colour visualization. SourceUsers could grab and select colour through a customised 3D colour space that has various colours flowing into each other. This colour space could be represented in the form of a cube, polyhedron, or sphere that floats and spins without any hierarchical up and down or left and right.

A possible basis for developing an educational experience with more inclusive depictions of humans could also being with a 3D sphere. Perhaps a model of the earth could allow users to select their ancestral lineage by holding it in their hands. This could also be a timely reason to play around with how we are taught to perceive the earth, considering that there is no up and down in space contrary to the image of the earth we all know, which is also historically imbued with social hierarchy in relation to the north/south, east/west divide.

These are just some rough jumping off points for connective design thinking in 3D space, inspired by the previously discussed examples. However, completely functional inclusive design that fits within a specific creative vision inevitably takes time and costs money. This is the crossroads where new media stands, and what we put value on now will play a major role in how future generations perceive each other. For too long media design has propagated the marginalisation of certain people through visual order, which has colonised our subconscious understanding of ourselves in relation to each other.

As designers and developers, we are active participants in constructing a new era in global human communication, so even if we lack the time and funds, taking responsibility for the work we can afford to make is nevertheless important. Being honest and uncovering uncomfortable truths of exclusion that do exist is a good starting point, so that our imaginations can be freed of old-fashioned stories and we can move forward together, aware and with greater control over the story of social reality to come.

I am a Virtual Reality Design Ethicist & Creator based in Berlin. If you would like to find out more about my research you can connect with me here.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and is fiscally sponsored by IFP. Learn more about our vision for the project here.