Part 7 in a series by Kamal Sinclair

Previously, we looked at some of the ways emerging media and technologies are changing the nature of privacy and furthering inequality by replicating old patterns of bias and inequity.

This article outlines possible interventions described by the project’s interviewees. The bulk of suggestions in this article relate to establishing ethical design practices and just policies.

- What does it mean to design for justice?

- Setting a clear mission and boundaries: One maker’s perspective

- What does it mean to design for well-being?

- What about ethics?

- What is design prosperity?

Earlier, the series discussed the recommendations related to adjusting the center of design or designing for the margins (as Cesar McDowell describes in his TEDx Talk), to ensure equitable inclusion and benefit from the diversity of thought in new media innovation. This article focuses on the need to explicitly design for justice and well-being.

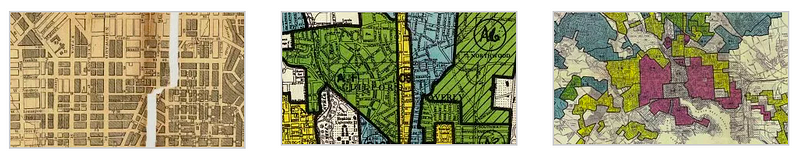

Maps made by financial

institutions in the early 20th Century that identify areas for investment based on race in

Baltimore.

Maps made by financial

institutions in the early 20th Century that identify areas for investment based on race in

Baltimore.The documentary Rat Film exposes how this design directly impacts socio-economic injustice in Baltimore today.

Throughout the research process, interviewees called for ethics in design standards, especially for consumer platforms. They wanted protections for individual rights and freedoms and the values of justice to be a top priority. They lauded actions like those of the Silicon Valley employees who left their jobs to launch the Center for Humane Technology to counter practices such as addictive design in interactive and social media, and praised research and watchdog organizations such as AI Now Institute or Coding Rights that are working to investigate how to design these just systems in code.

What does it mean to design for justice?

Organizations such as the Colloqate (creator of the Design Justice Platform), the Algorithmic Justice League, and Allied Media Projects (AMP) have been leaders in catalyzing thinking, practices, systems and pedagogy to help media makers design for justice. Sessions at AMP’s 2015 and 2016 conferences resulted in the formation of the Design Justice Network, which strives to “create design practices that center those who stand to be most adversely impacted by design decisions in design processes… to challenge the ways that design and designers harm Indigenous peoples, communities of color, poor and working class people, the sick and disabled, migrants, LGBTQ people, women and femmes… to imagine and build the world we need to live in — one that is safe and just.”

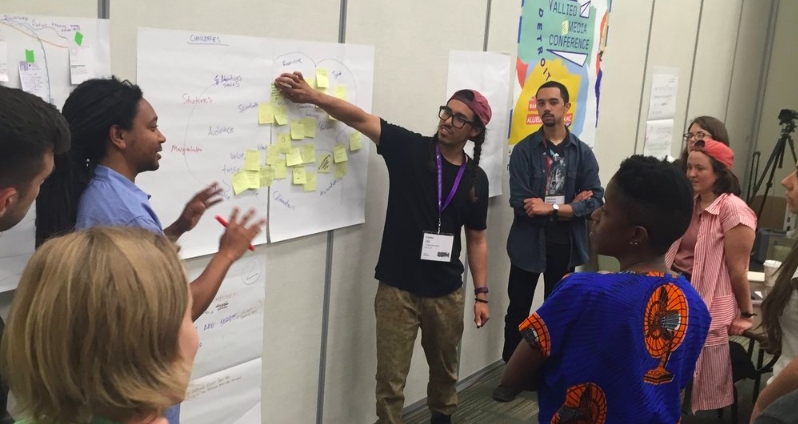

Strategizing around our shared principles at the 2016

Design Justice Network Gathering

Strategizing around our shared principles at the 2016

Design Justice Network GatheringThey have created a great foundation for how to do this kind of design, which adheres to the following set of design principles:

- We use design to sustain, heal, and empower our communities, as well as to seek liberation from exploitative and oppressive systems.

- We center the voices of those who are directly impacted by the outcomes of the design process.

- We prioritize design’s impact on the community over the intentions of the designer.

- We view change as emergent from an accountable, accessible, and collaborative process, rather than as a point at the end of a process.

- We see the role of the designer as a facilitator rather than an expert.

- We believe that everyone is an expert based on their own lived experience, and that we all have unique and brilliant contributions to bring to a design process.

- We share design knowledge and tools with our communities.

- We work towards sustainable, community-led and -controlled outcomes.

- We work towards non-exploitative solutions that reconnect us to the earth and to each other

- Before seeking new design solutions, we look for what is already working at the community level. We honor and uplift traditional, indigenous, and local knowledge and practices.

Similarly, Jamie Williams and Lena Gunn, who write for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, ask us to pause on the relentless design trend to solve everything with an algorithm, perhaps at the expense of well-being and better solutions. They point out a set of questions that everyone participating in the design of code should ask when designing technology to mitigate the negative ramifications of an algorithm gone wrong, as in Indiana’s welfare system algorithm that led to a child’s death; or how bias data erroneously racialized the prediction of child abuse the department of Children, Youth and Families (CYF) in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania.

The issues raised in the Minorities in Majority Spaces article last month are very complex and dynamic, with no easy answers for resolving the concerns. It will really take a deep education in our society, the elimination of unjust biases, and an ongoing process of developing genuine and authentic intersectional friendships and respectful working relationships before we see a decrease in “othering” and distrust.

However, there are a few principles that interviewees and researchers identified that build on and echo the Design Justice Network’s ideas for people working to create inclusive, safe, productive and equitable spaces:

- take an iterative approach to the ongoing process of your group, project, organization, or community development;

- communicate expectations clearly;

- establish protocols of participants to feel welcomed to express their thoughts and ideas, as well as raise any red flags that might hinder participation;

- allow people to set appropriate boundaries around their participation and engagement (i.e. ability to opt out of triggering processes);

- listen deeply;

- be aware of the dynamics of power and privilege, so you can help mitigate their impact on equity;

- consult on resolutions; adjust the design or process as needed;

- and check-in and reflect on the process or environment dynamics again.

In addition to these principles, we are seeing a growing use of legal instruments that require justice to be designed into the process of innovation or development. For example, many communities are adopting the Community Benefits Agreements that prohibit purely extractive relationships between entities and communities, or Inclusion Riders or Favored Nations contracts that aim to mitigate inequities in the entertainment industries.

Setting a clear mission and boundaries: One maker’s perspective

Filmmaker and activist, Sabaah Folayan, brought many of these ideas to this research. She had an insightful reflection on the need to engage in active communication about boundaries and expectations to achieve inclusion, noting “it is a matter of setting boundaries and requesting that expectations be made clear, knowing that we live in a world where most are conditioned to see black people setting boundaries as an act of hostility. In some cases, our attempts to set boundaries are met with responses ranging from anger and denial to tears over a perceived ‘attack,’ regardless of how calmly and kindly we approach the situation.” Being able to put one’s ego and defensive reflexes aside, calm the fight-or-flight instinct, and really listen, is critical for anyone working to be a part of an inclusive space (although it ain’t easy…and we are likely going to fail every once in a while). Folayan explained that “For white people whose physical well-being is not bound up in the eradication of white supremacy, this is most critical. They must be the ones to silence their visceral emotions and truly hear us, for those emotions are typically based on deep seated racial conditioning and an incomplete understanding of the reality we all share.”

Filmmaker

and activist Sabaah Folayan

Filmmaker

and activist Sabaah FolayanFolyan also states that it is important to be clear about the mission and expectations that an organization or organizer has of everyone participating in a process. This will allow people to negotiate adjustments and set personal boundaries ahead of active participation, as well as opt-in to the emotional, mental and physical labor involved in the process — or opt-out, if necessary. She reflected on Sundance Institute’s “standing commitment to diversifying racial perspectives in documentary” and said that its overt mission statement helps her and her collaborator, Damon Davis, move through some of the issues that have come up in the process of the increasing inclusion. These moments are critical in learning how to relate to one another in a fair and equitable way. I’ve had other experiences where there is not such an explicit mission statement, where the majority of the organizers do not have an active personal practice of deconstructing their conditioned behaviors, and in those instances addressing such problems becomes a lot more complicated.”

Folayan highlighted the need to always check the dynamics of your power and privilege, even as a person of color or member of a traditionally marginalized group. “Racism is an issue of life and death. Disparities affect healthcare outcomes, policing, environmental safety and every other area you can think of. It’s important to keep in perspective that those of us who have the privilege of making art, especially in such an expensive medium…who are privileged to be able to intellectualize these stories from a creative distance, need to recognize that privilege. We need to be bolder and more courageous in our conversations.”

I learned many years ago in grad school, in my consulting practice class, that setting clear terms and boundaries at the start of a relationship, may feel uncomfortable, but it is actually the greatest tool for securing long-term unity in any partnership or collaboration. Folayan reminds me of that principle when she says what might be perceived as “being difficult” is actually an attempt “within a silo, and without much leverage, to enact new patterns of interracial collaboration by refusing to submit to the idea that setting boundaries is an act of hostility, by refusing to cater to white fragility.” This is the hard work of moving equity, justice and unity further.

As the Detroit Narrative Agency so eloquently discussed in their response piece to the Radical Opportunity article, designing for justice starts with listening — something Folayan calls for here.

This concept is not a new one. American Society for Engineering Education published a paper called “What is designing for social justice?” in 2014 and it explicitly called for listening: “Although multiple stakeholders can play important roles, the dominant relationship is between community members and designers from engineering and other disciplines, informed by and seeking to enact social justice. In addition to listening to the local context, designers are challenged to listen to the structural conditions that gave rise to inequalities, including those that exist beyond the local context. That form of listening enables multidisciplinary design teams to broadly define the problem and propose solutions that attempt to increase human rights, opportunities, and resources, while reducing imposed risks and harms, all in order to enhance human capabilities.”

Finally, Folayan also prompts us to invert the perspective that increasing inclusion even means increasing minorities in majority spaces, when, especially in the case of “people of color,” you can expand the aperture to see the reality that the “minority” is the majority. She states that “many of our most acclaimed films feature people of color from around the globe, yet we limit our perspective to national boundaries when discussing authorship/defining who is a minority vs. a majority.” Folayan and Davis say they are “refusing to uphold the idea that we are a ‘minority’ when, in fact, we are part of an expansive diaspora which comprises a global majority.” I know it may be unprofessional, as this is a research paper, but Yes! She just helped me to re-evaluate my patterns of thinking that perpetuate the mythologies of white supremacy.

What does it mean to design for well-being?

During the opening session of Sundance Institute’s 2017 New Frontier World Building Residency at USC, we all had to answer the question “What job to you want to have in 2037?” My colleague Ruthie Doyle answered that she wanted to work for the organization focused on measuring the well-being of the world and designing for improving the world’s well-being. She imagined a well-being Index would replace the GDP as a countries top economic indicator of prosperity. This would be a more robust and critical economic and policy engine, than the current indices and reports that measure happiness.

Intentional Design for Human

Well-Being @ Philly

Tech Week 2017

Intentional Design for Human

Well-Being @ Philly

Tech Week 2017What would Doyle’s future work involve? Well, Philip Brey, a philosophy of technology professor at the University of Twente, discusses four design approaches that aim for creating greater human well-being in technology:

Emotional Design — a family of approaches that use design to evoke emotional experiences such as pleasure and other positive emotions. Patrick Jordan expands on that idea of pleasure by categorizing them as Physio-pleasure (Bodily pleasure deriving from the sense organs), Psycho-pleasure (Pleasure deriving from cognitive and emotional reactions), Socio-pleasure (Pleasure arising from one’s relationship with other people or society as a whole), and Ideo-pleasure (Pleasure arising from people’s values and tastes: cultural and aesthetic values, moral values and personal aspirations).

- Capability approaches to design — focuses on the enhancement of people’s basic capabilities for leading a good life. It rests on the assumption that people’s ability to attain well-being is dependent on their development and possession of a number of basic capabilities that allow them to engage in activities that promote their well-being, which are opportunities to do things or be things that are of value to them.

- Positive psychology approaches — an approach that focuses on studying and improving people’s positive functioning and well-being and focuses on the enhancement of creativity, talent and fulfillment. One very influential theory in positive psychology is that authentic happiness or a good life is a combination of three types of lives: the pleasant life, the engaged life and the meaningful life.

- Life-Based Design — a design approach that aims to improve well-being by looking at people’s whole lives and the role of technologies in them. Looking at whole lives involves studying people’s forms of life, values, and circumstances, and taking these into account in design. A form of life is a practice or “system of rule-following actions”, such as a hobby, activity, profession or family role.

From Lynette Woolworth’s

‘Awavena.’

From Lynette Woolworth’s

‘Awavena.’The Pew Research Center recently asked experts in tech and psychology the question: “Over the next decade, how will changes in digital life impact people’s overall well-being physically and mentally?” Although a little under half of respondents felt that technology will bring more help than harm, there was still a significant amount of concern about the possibility of technology causing more harm than good. However, they did collect a number of recommendations for how we might mitigate the harm and further well-being. Here are those “potential remedies”:

- Reimagine systems: Societies can revise both tech arrangements and the structure of human institutions — including their composition, design, goals and processes.

- Reinvent tech: Things can change by reconfiguring hardware and software to improve their human-centered performance and by exploiting tools such as artificial intelligence (AI), virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR) and mixed reality (MR).

- Regulate: Governments and/or industries should create reforms through agreement on standards, guidelines, codes of conduct, and passage of laws and rules.

- Redesign media literacy: Formally educate people of all ages about the impacts of digital life on well-being and the way tech systems function, as well as encourage appropriate, healthy uses.

- Recalibrate expectations: Human-technology coevolution comes at a price; digital life in the 2000s is no different. People must gradually evolve and adjust to these changes.

What about ethics?

Beyond the nine major areas of ethical dilemmas the World Economic Forum has identified for us to consider as we design an AI integrated future, which have been discussed in previous articles, interviewees called for bringing some “home training” into cyberspace.

There is a growing set of standards for educating youth about responsible participation in social media and protecting themselves online. However, producer Lisa Osborne called for a broader standard of digital ethics that go further than just securing human rights. She believes we should identify behaviors that can be taught in schools that can help us create less toxic online environments. For example, when is it acceptable to take someone’s photo and post it on smart platforms?

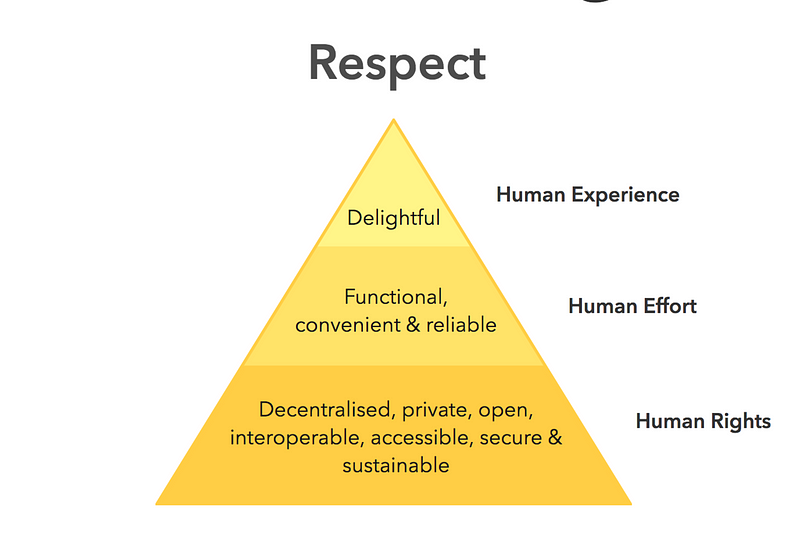

The ‘Ethical Hierarchy of

Needs’ (licensed under CC BY

4.0) (Source: ind.ie)

The ‘Ethical Hierarchy of

Needs’ (licensed under CC BY

4.0) (Source: ind.ie)Also, how do we transparently rate platforms and content in emerging media, so consumers have greater control over what they consume? Some argue that this could be a matter of including this content in existing solutions, like Common Sense Media or MPAA. However, some members of the sociology and the mental health professions feel that there is not enough empirical data on how these new media platforms impact our brains and behaviors to create appropriate rating systems. Related suggestions include developing robust parental controls for new devices and platforms to block negative content, block trackers on social media, or mitigate obsessive consumption.

Journalist and blogger Lindsey West lifted the veil on the psychological dynamics of troll and cyber-bully behavior when she confronted one of her cruelest trolls and he share with her his own unhappiness and low self-esteem. (Read this article to learn more.) Some experts explain that the root cause of these toxic online environments may be related to our mental health systems and a need for deeper, more enriching, community engagement. One of the solutions might be a cross-pollination of mental health professionals and developers in the design process. Designing for mental health could be a critical way of mitigating these underlying pathologies.

As Joe Unger of Pigeon Hole Productions pointed out, LA-based Riot’s League of Legends is a game with hundreds of millions in their fan-base. It was the first gaming company to hire sociologists and ethicists to create an in-game, user-driven justice system. Homophobia, sexism, and racism were reduced to 2% of all League of Legends matches. UCLA Law Professor Claudia Peña, Lecturer at UCLA School of Law, even suggested emerging media creators be trained in trauma-informed design practices: “Being ‘trauma-informed’ is one of the latest movements in the nonprofit sector. We’ve been developing curriculum to educate lawyers on how to be trauma-informed. It’s made progress in the field of medicine and social work, and it’s spreading to other industries. If we’re committed to not being stuck in siloed frames and wanting to reduce the possibility of harm, it would be helpful to think of VR creators as being trained in ‘trauma-informed’ programming or design.”

Another important perspective to have in the design process for interactive and immersive media is how one’s design might impact one community very differently than it impacts another. How do the stressors that come with poverty, disrupted or displaced family structures, or disabilities affect the impact of media content?

In a New York Times piece titled “America’s Real Digital Divide,” Naomi Schaefer Riley writes about “an initiative, called Truth About Tech, [which] aims to push these companies to make their products less addictive for children — and it’s a good start. But there’s more to the problem. If you think middle-class children are being harmed by too much screen time, just consider how much greater the damage is to minority and disadvantaged kids, who spend much more time in front of screens…While some parents in more dangerous neighborhoods understandably think that screen time is safer than playing outside, the deleterious effects of too much screen time are abundantly clear. Screen time has a negative effect on children’s ability to understand nonverbal emotional cues; it is linked to higher rates of mental illness, including depression; and it heightens the risk for obesity.” -

What is design prosperity?

An important point when making the case for design justice and design well-being is to note that these are synonymous with design prosperity.

During one of my trips for Making a New Reality, a white woman, very dedicated to justice, asked, “How do we convince white people to give up their wealth and prosperity to share with others, so we can have more equitable and inclusive space?” I was struck by the premise, because I never even considered that establishing justice, equity, and inclusion meant that people that currently think they are benefiting from systems of injustice, inequality, and exclusion would have to lose anything (except unbridled power). I’ve always understood that “white people,” or those who are at the top of current systems of unjust power, were already operating in a severe deficit.

By explicitly or implicitly perpetuating systems of oppression, we limit the body of humanity from accessing the majority of its potential. Diversity, equity, and inclusion are not a zero-sum proposition — they are actually strategies of sustainable abundance and well-being. We have been operating in an ecosystem that has critical parts of what makes it work extracted. When we design for the margins and for justice, we establish balance and allow everyone to benefit from the development of these latent human potentialities.

The Making a New Reality research project is authored by Kamal Sinclair with support from the Ford Foundation JustFilms program and supplemental support from the Sundance Institute. Learn more about the goals and methods of this research, who produced it, and the interviewees whose insights inform the analysis.

Immerse is an initiative of MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.