In Jeremey

Mendes and Leanne Allison’s Bear

71 (2012), the narrative constraint is expressed through a personification

of a bear.

In Jeremey

Mendes and Leanne Allison’s Bear

71 (2012), the narrative constraint is expressed through a personification

of a bear.Why less can be more in digital storytelling

With all of the interactive possibilities now available for digital narratives, it may come as a surprise that some of the most ground-breaking artists are deliberately putting constraints on the tools and methods they use — even as the VR-extended family of technologies seemingly enable limitless fields of view, and computer software and hardware allow for unprecedented levels of interaction.

Why would creators choose to impose constraints on their work, limiting newly acquired technical freedoms? A look back sheds some light.

Jonathan Harris’s I Love Your Work (2013) follows nine women who make their living in the lesbian porn industry. The project is comprised of 2,202 video clips, each ending—or, rather, stopping—after 10 seconds. The justification of imposing this constraint is the length of the teasers on those websites, and the project clips are abruptly cut in a similar way. While the cuts seem arbitrary, they create a unique style, as the project is not exactly a film or a single video but rather a new cinematic being. The story is enhanced by the fact that the medium is unique, and the viewer’s attempt to decipher the content and form is performed in unison. It is an example of how imposing a constraint on a story generates a new, potential, self-contained world of multitudes.

Digital media has made an almost infinite amount of data available, and many stories, especially documentaries, are fed from inputs that need to be filtered. In this case, imposing constraints on data may be enough to create a story. This computational filtering method consists of two building blocks that construct many visual stories: data selection and data projection.

- Data Selection means taking only the data elements that fulfill a certain condition. In Fabrice Florin’s Moss Landing (1989), the footage for the project was all captured during a single day in one coastal town with the intention of creating “a live postcard.” This work inspired many others. By fixing the time and place, Florin formed an inner world, which allows the viewer to better immerse themselves in it and ignore anything else.

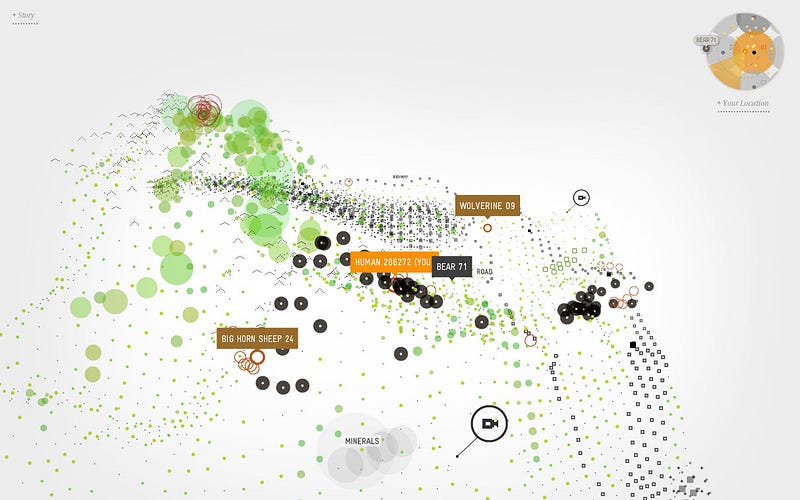

- Data Projection means focusing on several attributes, but allows the manipulation of those attributes in order to present them differently. La Burthe, Colinart, Spinney & Middleton’s Notes on Blindness (2016) focuses on the eyesight attribute; the project enables the viewer to feel what it is like to go blind. In order to do so, the visual objects undergo a twofold projection: the objects themselves are shown blurred, and they are represented to the viewer through corresponding sounds. In Jeremey Mendes and Leanne Allison’s Bear 71 (2012), the narrative constraint is expressed through a personification of a bear.

Many artists don’t just impose limitations on themselves but create in an environment that has its own built-in constraints. Digital storytelling often refers to the presence or absence of the cinematic frame. On the one hand, the fact that in VR there is no filtering frame allows more freedom. On the other hand, the infinite canvas does not necessarily mean that there aren’t different constraints imposed by new technologies. A partial list of constraints in VR, for example, would include the weight of the headset, the difficulty to walk while wearing it, and the fact that most people cannot wear it for more than 15 minutes. Interactivity creates its own built-in limitations by forcing a certain interface on the users. Decentralized or distributed works have to obey the rules of computer networks, etc.

I suggest turning to a different historical lineage: to think of digital storytelling in relation to 20th century poetry. Poetry has escaped its own prison of rhyme and meter, creating “free verse” to enable total expression of the self, “not in sequence of a metronome,” as Ezra Pound wrote.

While free verse is the prevalent form of contemporary poetry, whether it is free or not is disputed by many. The Language poets claimed that the new constraints of “free” verse are being imposed by language, mainly by the sentence (“That’s what we call it when we put someone in jail,” said Robert Creeley). Ron Silliman formed The New Sentence. Language constructs—along with their attached cultural biases—have been challenged by poets, often by using constraints.

Oulipo is a French literary group formed in 1960 that utilized constrained writing to explore the potential of literature. Founding member Raymond Queneau published Exercises in Style in 1947, an experimental book depicting the same scene in a hundred different styles, or data projections. The most famous member of the group, George Perec, wrote La Disparition, about the disappearance of the letter “e” without using it, thus employing data selection. American poet Bob Perelman expressed a sudden shocking feeling by writing only the first five words of each sentence in Chronic Meanings. Many other examples show that constraint-based writing foreshadowed many tricks and techniques in digital storytelling.

It may be both challenging and useful to think of a visual storytelling version that correlates to works such as Anne Garréta’s Sphinx, which details a romantic affair without disclosing either of the lovers’ gender. Such a constraint feels intimately related to VR or first-person visual storytelling works.

Parts of digital storytelling are evolving towards algorithmic storytelling, and constraint-based works may serve as a portal to this realm. Chatbots have become popular in the last couple of years, due to the fact they can demonstrate various levels of non-human agency. They are constrained due to the limits of their programming architecture.

Bots can be rule-based or data/example/machine learning-based, but, in any case, they serve as artificial beings. This allows humans to open up to a different kind of conversational being, and offers a comparison between humanity and software.

While it may seem to contradict the passion of creators to express themselves freely, thinking in terms of constraints may help them to find their own free path within the infinite possibilities. Constraints humans impose on their creations are an extension of human behavior, allowing us to realign ourselves to a digital culture in the same sense that art filters reality to reflect ourselves.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.