Are makers flying too close to the sun in their claims of impact?

First up, a test: recognize this?

Spot the

legs.

Spot the

legs.It’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus by Pieter Breughel the Elder (or at least a copy from a lost original of his). As we all know, in Greek mythology, Icarus used wings made by his father Daedalus held together with wax to fly. However, he ignored his dad’s advice and flew too close to the sun, melting the wax and sending him plummeting into the ocean, where he drowned. W. H. Auden sums this up best in his poem, Musee des Beaux Arts (named after where the painting hangs in Brussels):

About suffering they were never wrong, The old Masters: how well they understood Its human position: how it takes place While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting For the miraculous birth, there always must be Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer’s horse Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry, But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky, Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

Despite the epic scene, we can clearly see the ploughman in the foreground’s attention is elsewhere, a nod to the popular (so I’m told) Flemish saying “En de boer … hij ploegde voort” (And the farmer continued to plough…), pointing out that so many of us continue the quotidian business of our lives, seemingly oblivious, while others continue to live in suffering.

Updated to the present day, Teju Cole writes in “Death in the Browser Tab” for the New York Times:

There you are watching another death on video. In the course of ordinary life — at lunch or in bed, in a car or in the park — you are suddenly plunged into someone else’s crisis, someone else’s horror. It arrives, absurdly, in the midst of banal things. That is how, late one afternoon in April, I watched Walter Scott die. The footage of his death, taken by a passer-by, had just been published online on the front page of The New York Times. I watched it, sitting at my desk in Brooklyn, and was stunned by it.

In this media-saturated, constantly refreshing, auto-playing infinite scroll media landscape, how can we recalibrate our sense of perspective and engaged relationship to the stories we are told?

So many of us continue the quotidian business of our lives, seemingly oblivious, while others continue to live in suffering.

Today I’m going to talk about this notion of suffering, and how in recent years virtual reality has claimed its stake as the remedy to countering this “human position” of indifference, or at least causing enough of a stir to make our ploughman curious during his daily routine. It will centre around the study I was commissioned to research at the Tow Centre at Columbia on empathy in VR but will also look at how we as journalists, directors, and media makers should be thinking about audiences, attention spans, and the effect we want to have through our stories—not to mention, as the title suggests, dismantling the trite notion of VR as an empathy machine.

Hitting Peak Empathy

Moving from the sublime to the ridiculous, as the founder of a company called Empathetic Media, I’m all too conscious of the medium overtaking the message when it comes to virtual reality’s role as an empathy machine. This often means the best of intentions, poorly executed — as you can see in this photo of Norwegian Foreign Minister Sylvi Listhaug trying to simulate a refugee’s experience of crossing the Mediterranean.

Making a splash for all the wrong

reasons

Making a splash for all the wrong

reasonsPaul Bloom’s Against Empathy and his rallying cry that the real empathy machine is actually a book for its affordances of longer, sustained engagement and character interiority and development rails against the notion of empathy as a disposable, transactional experience reachable simply through the sensory stimuli of pre-recorded footage. Likewise, many have urged the need to heed the exploitation of the medium as a form of “disaster porn,” where disembodied voyeurs explore scenes of suffering, their gazes unreflected by those on the other side of the spherical camera lens. The proximity of our virtual experience is no panacea to our proximity to understanding life from their perspective. A message best sardonically summed up by the @barbiesavior account on instagram:

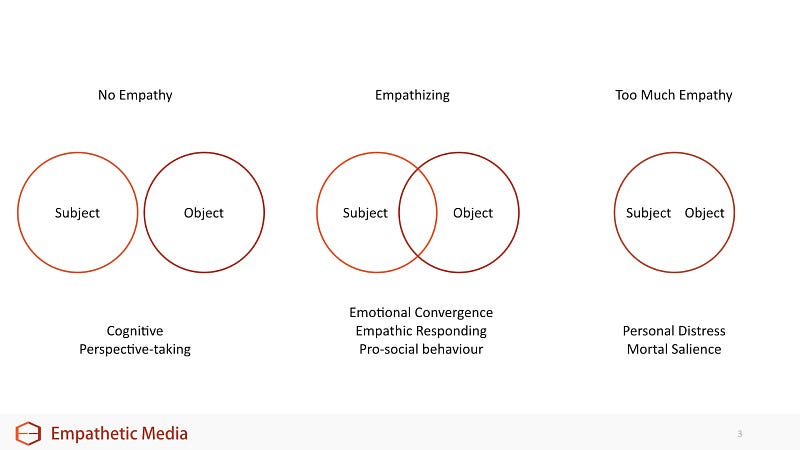

It is worth pointing out that there is a sliding scale of empathy, ranging from the rational, cognitive appreciation of someone’s situation through to deep, emotionally charged affect, which can actually trigger a self-protecting distancing mechanism when someone feels another’s pain too keenly.

As storytellers, we need to find a balance that allows for the operationalization of empathy — namely, for the subject to be affected and take action after their experience, not to feel relief that their situation is different to what they have just experienced. There is such a thing as too much empathy, which often triggers the opposite of the desired effect, where extreme sensations of discomfort (a.k.a mortal salience) overwhelm an individual, prompting a strong feeling of aversion. Mortal salience is defined as “the awareness by an individual that his or her death is inevitable.” The term is prevalent in terror management theory, which posits that it causes existential anxiety that may be mitigated by an individual’s cultural worldview or sense of self-esteem.

Empathy is an inherently emotional and unstable response, which is often triggered in particular instances. Paul Slovic, Professor of Psychology at the University of Oregon (drawn below at the Frank conference) is a leading scholar on decision theory, coining the terms “psychic numbing,” ”pseudo-inefficiency,” and “prominence effect”: terms describing our bias towards being overwhelmed by the scale of mass tragedy but empathizing greatly with individuals, as was the case with three-year old Alan Kurdi, whose body washed ashore on a beach in Turkey, prompting huge public outcry.

Dr Paul

Slovic, sketched live at the Frank Conference in

Gainesville, Florida

Dr Paul

Slovic, sketched live at the Frank Conference in

Gainesville, FloridaWe can all relate to the saying “One death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic.” Due to psychic numbing, our sympathy for suffering and loss declines precipitously when we are presented with increasing numbers of victims. —Paul Slovic, The Arithmetic of Compassion

Our Study

In 2016 I was a Tow Fellow at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University. My fellowship pitch was an investigation into the metrics of the then-nascent VR journalism scene, trying to quantify both audience reaction and impact of this new form of storytelling. At that point, only the larger media organizations (such as The New York Times’ initiative with Google Cardboard) had taken the plunge and invested in it.

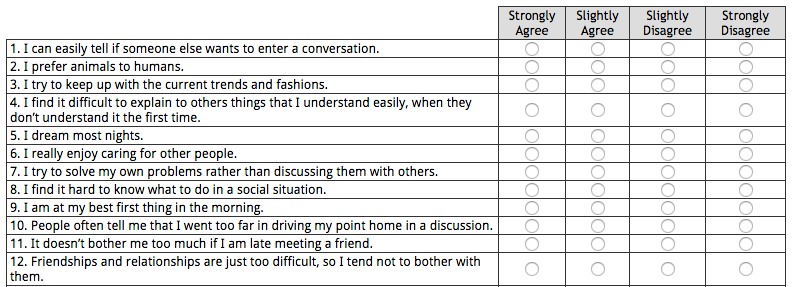

Was VR the ideal tool to counter this response to the stories of mass suffering that so frequently make the headlines and make readers sit up and pay attention? In order to find out, my team (comprised of statistician Katharina Finger and PhD student Max Foxman) and I needed to devise a system of measurement. Below is a glimpse of The Empathy Quotient test — a 60-item questionnaire (there is also a shorter, 40-item version) designed to measure empathy (or, more pointedly, the apparent lack of it) in adults. The test was developed by Simon Baron-Cohen at the University of Cambridge’s ARC (Autism Research Centre).

The Interpersonal Reactivity Index — Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) is a published measurement tool for the multi-dimensional assessment of empathy. It was developed by Mark H. Davis, a professor of psychology at Eckerd College.

IRI is comprised of four subscales:

1. Perspective Taking — the tendency to spontaneously adopt the psychological point of view of others

2. Fantasy — taps respondents’ tendencies to transpose themselves imaginatively into the feelings and actions of fictitious characters in books, movies, and plays.

3. Empathic Concern — assesses “other-oriented” feelings of sympathy and concern for unfortunate others.

4. Personal Distress — measures “self-oriented” feelings of personal anxiety and unease in tense interpersonal settings.

We asked our participants to fill out a shortened version of the EQ test, but found no statistically significant correlation between those who scored highly on the test and their responses to the treatments. It turns out the majority of us consider ourselves to be more empathetic than what might actually be true!

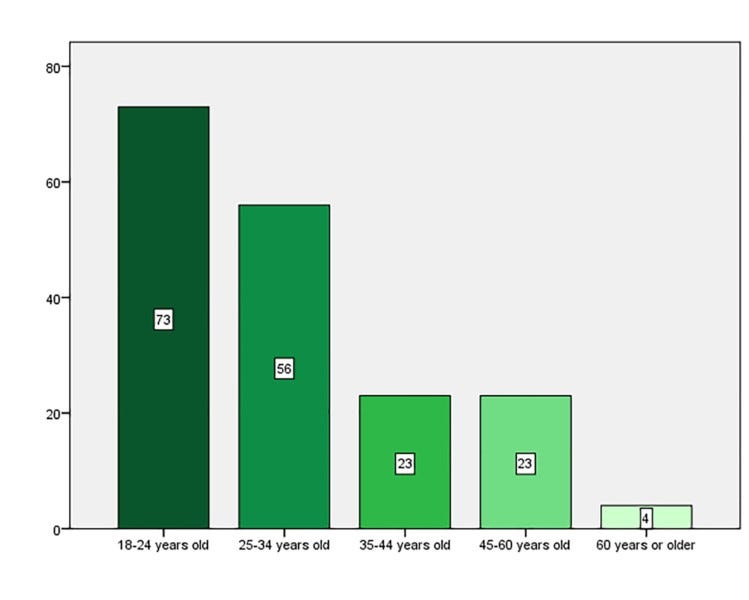

We surveyed 180 participants, sixty-nine of whom were women and 111 men, representing a gender balance of 38.3 to 61.7 percent. The overall age range of participants had a noticeably younger bias, with the older generation under-represented. We recognize the bias toward a younger audience in our sample, with 71.7 percent of the total responses coming from millennials aged 18 to 34. We felt this corresponded to the heightened amount of interest in emerging technology among younger populations. For further tests, the age groups were combined into four major groups: college-aged students, eighteen to twenty-four; young adults, twenty-five to thirty-four; middle-aged adults, thirty-five to forty-four; and those aged forty-five years and above.

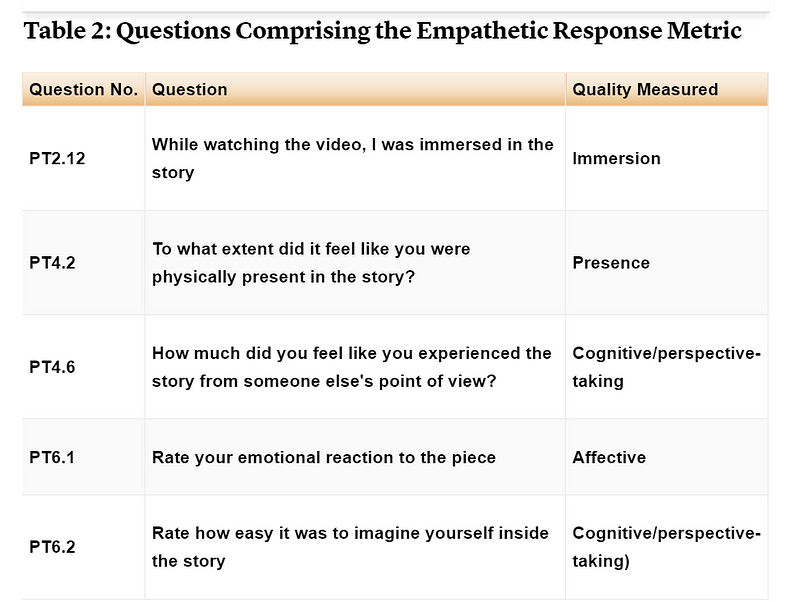

In devising our own metric of empathy, as you will have guessed from the quick literature survey above, we were very aware that empathy is a nebulous term comprised of multiple components. Therefore we isolated for perception, emotion, and motivation: a user’s self-reported sense of presence, their ability to perspective-take, and their likelihood of taking action based on their experience. Results were based on a self-reported seven-point Likert scale:

Our combined

metric for assessing empathy

Our combined

metric for assessing empathyWe presented three news stories across three different formats: VR in a head-mounted display, VR on a laptop (using a mouse to scroll and explore the 360 space) and a transcribed text article of the experience with photographs as the control.

The three 360 videos chosen were all produced by HuffPo RYOT and all were around 5 minutes in duration. Growing Up Girl was told by one young female protagonist and focuses on gender equality in Sub-Saharan Africa; Seeking Home (see below) chronicled the lives of several refugees in the Calais Jungle camp; and Act in Paris was told purely in voice-over, without any central character.

Findings

Now that you know more about our participants, let’s skip to the findings, starting with those related to story.

Audience over-familiarity with a story can negatively impact the level of immersion and enjoyment of a story. Immersion and presence in VR are key, but they still can’t outweigh a user’s disinterest in a subject. A case in point here was the poor performance of the Seeking Home treatment, which might be anecdotally attributed to the saturation of refugee-related news stories around the time of the survey. Its mean score in emotional impact was lower across all of the story formats by up to one full point on the seven-point Likert scale.

One example of this correlation between the familiarity with topics and the level of empathetic response was applied to the climate change piece, Act in Paris, in which those who reported that they were least interested in the topic actually registered the most empathetic response. Conversely, those who reported a general interest in climate change did not respond empathetically to the story, which suggests that these stories are best directed at newcomers to particular topics, or utilized as introductory pieces to new stories. The same novelty factor also applied to news consumption in a broader sense: the lower a user’s news consumption or familiarity with the technology or story, the more likely they were to be positively impacted by the virtual reality format.

Another contributing factor might be the fine line that filmmakers have to tread between showing scenes of hardship and suffering to raise awareness, and not overly upsetting their audiences in the process, especially when participants feel as though they are in the scene, thanks to VR’s affordances.

Compared to the squalid conditions of the Calais Jungle refugee camp in Seeking Home, “enjoyable” visuals (even if they’re alluding to less enjoyable themes such as catastrophic climate change) are most likely to have the most impact on users.

A statistically significant relationship was also found to exist between the participant’s level of immersion and their desire to take action.

Interestingly, those with a reported immersion level of five out of seven on the Likert Scale responded “very strongly” in terms of their motivation to take action: higher than that saw the motivation level drop a full point. This supports the hypothesis that over-immersion in stories can actually hinder an audience’s desire to remain motivated beyond the end of the narrative.

Stories with one clear protagonist as a guide were also consistently found to be more enjoyable for users.

Monica, the

lone protagonist in Growing Up Girl

Monica, the

lone protagonist in Growing Up GirlOne clear protagonist that is consistently on screen builds narrator trust, which facilitates an empathetic connection and heightened engagement in the narrative, corroborating Professor Slovic’s point from earlier. This is clearly seen below with the two stories featuring on-screen narrators (Seeking Home and Growing Up Girl) scoring highest. The discrepancy between the two might be due to the fact that there are multiple characters in Seeking Home, none of whom are on screen throughout, hindering a strong connection with the audience. This sense of closeness to the narrator also plays a significant part in participants’ reported level of immersion: those who trusted the narrator moderately strongly (mean = 5.06) or very strongly (mean = 5.73) felt more immersed, compared to those whose trust was registered as moderately weakly (mean = 2.5) to a little weakly (mean = 3.56). There is also a significant difference between participants who trust the moderator a little strongly (mean = 4.24) compared to very strongly, confirming once more the importance of the narrator.

A trusted narrator can increase users’ sense of immersion.

Focusing more on the format, VR (immersive and non-immersive) generated a higher empathetic response than the photo/text treatment. In the longer term (two and five weeks after viewing initial treatments), the higher the empathetic response, the higher the likelihood was of respondents being able to recall the stories they watched. Another important distinction that was noted between the VR treatments versus the text control was the level of user motivation to find out more about the subject, which also highlighted the correlation to emotional impact. Those who received the text treatment were thirteen to eighteen percent less likely to find out more about the subject when compared to the immersive/non-immersive treatments.

A study

participant livesketched during her experience

A study

participant livesketched during her experienceOne shortcoming of the immersive format, however, was that despite users’ reported higher levels of immersion, they did also register a higher amount of discomfort, although its moderate level implies this was more to do with the physical sensation of using the HMD for the first time as opposed to the more profound feelings of mortal salience (as mentioned above).

Users experiencing the stories in either VR format were more likely to recall the stories, be motivated to find out more about the subject, and to take “political or social action” after viewing.

Perhaps most surprising of the results was the negligible difference in the level of both perceived interactivity and presence between the HMD (immersive) and desktop (non-immersive) VR treatments. This will assuage some of the doubts many have had about the difficulty in attracting casual viewers to the medium, as well as complicating what many assume is the unique selling point of Head-Mounted Display (HMD)-based Virtual Reality.

The Future

Story is still the most important factor for discerning an individual’s response to a treatment, regardless of format. VR is a powerful tool for presenting topics to an unfamiliar, casual audience, and giving them a brief exposure to a topic that they are then likely to be curious about afterwards.

In that sense, VR is more of a speed-dating machine than one designed to build empathy.

However, we must also reflect, beyond the scope of this study, just how much empathy and nuanced understanding of a topic anyone can achieve when exposed to a story for a mere five minutes (the standard duration of most cinematic VR experiences). Going back to our ploughman at the beginning, we need to build a space where audiences’ expectations of new narrative experiences are in line with their commitment to them: you’re unlikely to empathize with anyone (real or virtual) if your attention is constantly diverted, or you’re trying to interact with them in a noise-filled environment where you can’t hear properly. The question lies in how we can build this attentive space of reflection, physically and mentally, into news consumers’ regular routines.

It is also critical to recognize VR’s role in a journalist’s toolkit as a device to embellish existing modes of storytelling rather than replace them wholesale. Coupled with a longer-term form of exposure, perhaps through an episodic narrative released over the course of several weeks that charts a protagonist’s journey, we could overcome some of its criticisms, such as its superficial or reductive nature.

In subsequent research, I hope to build on the findings to incorporate more physiological data through biofeedback devices (measuring skin conductivity, heart rate, blood pressure), compare and contrast 360 video with computer-generated (CG) VR, as well as look at virtually reconstructed environments as spaces for preventative training and not only post-traumatic therapeutic treatment.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.