Museum of

Other Realities will be hosting two immersive festivals in June 2020 with XRHAM! and

XRCannes.

Museum of

Other Realities will be hosting two immersive festivals in June 2020 with XRHAM! and

XRCannes.For years, the film festival circuit has been an opportunity for immersive artists to experiment and explore the storytelling potential of emerging technology devices, haptic devices, bone conduction headphones, experiments with smell and taste, immersive theater productions, and multiplayer, social experiences. Many of these experimental demos are impossible to experience at home because they go beyond the technologies the average VR consumer has access to.

For the foreseeable future, this pandemic will continue to disrupt the location-based entertainment industry, including the major film festivals and the exhibition of immersive art at museums. Cultural institutions will be forced to reconsider how to distribute work virtually and how to continue to connect with audiences.

The film festival circuit has been able to cultivate an audience for immersive storytelling that includes funders, curators, creators, and some nascent press attention. The funding cycles for these experimental works largely revolve around premiering at one of the major festivals on the circuit, whether it’s Sundance, SXSW, Tribeca, Cannes, or Venice. This has created a flow and rhythm of deadlines that catalyze artists to complete an iteration of their work to be shown and experienced by audiences. Since these traditional distribution channels have been disrupted, then what are the emerging options and solutions for showing work virtually?

Since these traditional distribution channels have been disrupted, then what are the emerging options and solutions for showing work virtually?

It’s tempting to answer this question by focusing on distribution channels and technology platforms, but I think it’s also important to break down the other elements of community and culture that organically emerge as a result of makers and stakeholders physically gathering on the festival circuit to show, experience, analyze, and critique immersive work.

GOING VIRTUAL WITH TRIBECA IMMERSIVE

Tribeca

Immersive Cinema360 programs were shown on Oculus TV in April 2020.

Tribeca

Immersive Cinema360 programs were shown on Oculus TV in April 2020.Tribeca Immersive was the first film festival to explore new virtual distribution due to the pandemic. From April 17th to April 26th, Tribeca streamed the 15 cinematic VR experiences that were a part of their Cinema360 program on Oculus TV.

While there were a few pieces with significant compression artifacts resulting from streaming, the streaming quality for most videos was indistinguishable from watching it from a downloaded version. Overall, I’d say that I was able to recreate the essence of experiencing a cinematic VR program in the comforts of my own home.

Oculus TV is only available on the Oculus Quest or Go. Despite this limitation, Tribeca Immersive Chief Curator Loren Hammonds said there were over 46,000 total streams of the program, which is “exponentially higher than what we would have been able to serve at the in-person festival. Across 10 days, the Cinema had only been projected to serve approximately 4,000 guests.”

Therefore, we can see that virtual access caused a spike in audience attendance to the benefit of the festival. However, a vital aspect of public festival screenings is how they gather the community together to share in real-time the same content curated by the programmers, and to talk about the experiences with each other. These public screenings serve as a calibration process for individuals to compare their experiences with the consensus emerging from the community buzz and zeitgeist of a gathering. These shared collective experiences also catalyze the development of language and conceptual frameworks that help critics and viewers to analyze, critique, and talk about the work.

These shared collective experiences also catalyze the development of language and conceptual frameworks.

With little time to try to create a virtual substitute, Tribeca hosted a series of four At Home Tribeca Talks posted to Facebook featuring a discussion between the directors from each of the Cinema360 programs moderated by Ingrid Kopp, Loren Hammonds, or myself. Pre-recording it allowed for video clips to be cut into the discussion, but in retrospect, I would have preferred a livestream version that invited live audience questions and interaction. This would help replicate some of the live social engagements that emerge on the festival circuit.

In the future, I would also like to see more effort to organize informal meetups within VR to gather and discuss the work. This is a crucial component of the culture of festival gatherings but will take deliberate and intentional effort to cultivate virtually.

A SURVEY OF EXISTING DISTRIBUTION DYNAMICS FOR IMMERSIVE STORIES

Because distribution platforms such as Steam and Oculus have focused primarily on gaming, the primary distribution channels for featuring immersive stories has been the film festival circuit. The virtualization of these festivals will hopefully create both time-limited and ongoing distribution channels for this type of immersive storytelling work, and potentially create better economic feedback loops to sustain future work.

Immersive creators have commonly embarked on “festival runs” before exploring mass distribution options. This practice of showing at festivals for a year or more seems to be adopted from the independent film community. The distribution channels for independent film and criticism are a lot more mature than for XR, and so prolonged festival runs can create a big gap between the initial debut and eventual public launch. This makes it harder for XR journalists to cultivate an audience for covering this work, and it’s also difficult for audiences to remember the original buzz from something that premiered one, two, or three years ago.

One notable exception can be seen in the path taken by the successful team of Felix & Paul, who have avoided extended festival runs and instead have used festival premieres to publicly launch nearly all of their projects through Oculus’ distribution channels. They’ve certainly benefited from being produced by Oculus Studios, but this approach has meant that they’re able to leverage the press event generated from the festival premiere to make their work widely available to everyone on the Oculus platform.

I’d love to see more immersive artists take this approach, but the post-production of 360 video is different than it is for interactive experiences. Cinematic VR is similar to film in that it can be locked down in an edit and remain the same throughout a festival. But for interactive experiences, sometimes there are changes or bug fixes that happen daily.

Interactive experiences are able to gain a lot of novel user testing feedback at a scale and diversity of experienced users that’s harder to gather before a public launch. The live and interactive nature of festival screenings has allowed for experimental and partially completed works to be shown and developed. It’s analogous to an early release on Steam where beta versions can be tested and iterated on in order to add the final polish for a release based upon user feedback.

I know the curation at Sundance over the past couple of years has emphasized technological innovation and experimentation with storytelling, while SXSW has tended to feature some of the more polished works intended for larger public releases. There will continue to be a diverse range of curatorial intentions between the festivals, but the lack of clear distribution channels for immersive stories has been a persistent problem.

The lack of clear distribution channels for immersive stories has been a persistent problem.

The gaming-centered focus of both the Oculus and Steam distribution platforms has meant that the more experimental narrative pieces have traditionally not been as welcomed or well-received on these platforms. This was first made clear by the racist & vitriolic reviews Nonny de la Peña received on Steam for Project Syria in 2016. Even though Céline Tricart’s The Key won the top prizes at Tribeca and Venice, there are still around 10–15% of review bombers who give 1-star reviews because it’s not a game, or because they disagree with the political message.

The mobile Oculus Quest platform seems to be taking off and gaining a lot more traction than the PC-based Rift did, but it’s also extremely difficult for independent developers and storytellers to secure distribution on the Quest. Experiences have to be optimized for the Quest, which requires a lot of technical aptitude and resources.

But the bigger challenge is that the Oculus curation team is still primarily focused on gaming, and so they’re less likely to distribute the type of work that has typically debuted on the festival circuit. The last couple of weeks has been a notable exception with the launch of immersive stories such as The Line and Gloomy Eyes on Quest as well as War Remains and Queerskins on Rift, and so I asked Facebook if this represented a shift in their curatorial vision.

Colum Slevin, Director of AR/VR Media at Facebook, said, “Although gaming remains central to our content strategy in VR, we’ve had a passion for narrative VR since the early days of the Oculus platform with Henry and Dear Angelica. This is still a strong focus for the AR/VR team and we’re making it easier for people to find, enjoy, and share the best immersive narrative experiences in Oculus TV.”

The Oculus TV app has a dedicated icon on the Quest’s Navigation tab, and Facebook is hoping to make it the primary portal for downloadable immersive story applications. Oculus TV originally streamed 360 videos, but it now features sections of “Critically Acclaimed Free Downloads” and “Premium Downloadable Experiences” that link to the store pages for immersive story apps. This is a step towards co-locating storytelling so the experiences do not have to fight for real estate alongside premium gaming content. This may allow Oculus to continue pushing “the boundaries of storytelling in VR and elevate storytellers and creators” as Slevin says. However, having “TV” in the title of the app doesn’t immediately invoke an image of premium interactive stories. As well, these stories are rated using the same Oculus store backend as other Apps & Games, rendering them susceptible to review bombing from gamers.

Many independent VR game developers who were not able to secure official distribution on the Oculus store have turned to sideloading content for the Quest using Side Quest, but these are usually low-budget indie games that were rejected from the Quest store. The Side Quest still primarily targets members of the gaming community looking for more innovative and experimental gameplay mechanics. Sadly, immersive narratives can easily get lost there.

There have been a number of PC-based immersive stories distributed on Viveport, but it hasn’t gained the level of traction and adoption as Oculus or Steam. Companies such as Atlas V, which was originally focused on location-based entertainment as their primary distribution option, have been focusing on releasing experiences such as Ayahuasca on Steam and then promoting them to niche communities online.

Makers of cinematic 360 videos have a lot more options for distribution, including YouTube VR, Within, AmazeVR, VeeR, and Oculus TV, as well as some emerging curation from Amazon and Hulu. There have also been other fledgling 360 distribution video apps such as Wevr, Jaunt, and Samsung Video, but YouTubeVR or proprietary apps such as the one created by the New York Times seem to be some of the top outlets for 360 video distribution.

My impression is that because most cinematic VR pieces are distributed for free, there has been either nominal or negligible compensation, which has not made it a viable business venture for many independent producers. The animation work from Baobab Studios has had the broadest distribution that I’ve seen, but overall the market is still in too early of a stage to support a diverse ecosystem of cinematic VR producers.

Because the dominant existing distribution channels are primarily focused on gaming, artists creating immersive art and interactive stories have turned to the film festival circuit and location-based entertainment runs at museums. With the COVID-19 pandemic, these channels have been disrupted. So let’s take a look at one of the most exciting and emerging distribution options debuting in June.

MUSEUM OF OTHER REALITIES AS AN EMERGING DISTRIBUTOR OF FILM FESTIVALS

The VRHAM!

Virtual Reality & Arts Festival will be taking place online in The Museum of Other

Realities.

The VRHAM!

Virtual Reality & Arts Festival will be taking place online in The Museum of Other

Realities.The Museum of Other Realities (MOR) was launched by Robin Stethem & Colin Northway on February 26, 2020, to feature the work of immersive artists in this virtual museum. You can navigate around an amazing space to look at or interact with 3D art pieces as you would in a normal museum, but you can also seamlessly teleport into the art itself. Imagine seeing a table-top scaled version of a Tiltbrush painting and then being able to shrink into the world while also seeing giant avatars hover outside.

The MOR sets a broader cultural context to receive works of art, just as existing cultural institutions have been able to do. The interior of the MOR was designed by Samuel Arsenault-Brassard, Katie Davis-Sayles, and Claris Cyarron, and it’s some of the most impressive immersive architecture I’ve seen. It lacks any 90-degree angles and creates a vast open space with shapes that feel like they could only occur in VR. This amplifies the experience of wonder and awe of exploring the MOR, but it doesn’t detract from the art itself.

The MOR has built a solid foundation and infrastructure to potentially become one of the leading virtual distribution channels for immersive art and location-based entertainment experiences. Rather than downloading an app for each experience, the MOR can do ephemeral distribution of Unity & Unreal executable binaries that would normally be shown at film festivals.

Co-founder Stethem said that updates to the MOR are usually around 1GB, but they can push an update of 40–50GB that contains all of the immersive experiences normally shown at a festival. Northway told me that they’re still deciding whether to let attendees download the entire program all at once or let them selectively download an experience.

Kaleidoscope VR started as a traveling VR festival in 2015 and has since evolved to providing artist grants, events, & networking for the creative community. Founder René Pinnell saw the potential of the MOR to become a viable distribution platform for the types of immersive experiences curated by film festivals, and he has become the virtual venue’s exclusive event coordinator. The MOR and Kaleidoscope will be distributing all of the Hamburg VRHAM! Virtual Reality & Arts Festival for eight weeks starting on June 4, and they will also be distributing CannesXR in partnership with Tribeca Film Festival and VeeR for 10 days starting on June 24th.

The MOR and Kaleidoscope will be distributing all of the VRHAM! Virtual Reality & Arts Festival for eight weeks starting on June 4.

Film festivals have been encouraging creators to build installations to help audiences transition from the world into the magic circle of their experience. The MOR provides similar transitions going from the main area into the immersive pieces curated by the festival.

There is typically more demand to see the work at immersive festivals than the physical capacity to screen it. Sundance curator Milo Talwani told me there have been two main options for solving this throughput dilemma: either curate less work or expand to more venues. If everyone is using their own VR hardware, then this is functionally expanding the number of venues.

Virtual distribution may introduce new technical challenges for audience members who do not have hardware with the minimum specifications. Creators typically optimize performance for an official release, but virtual distribution introduces new creative constraints, since a lot of festival pieces use the latest, top-of-the-line hardware, and potentially even multiple machines. It will be up to each distribution platform to develop their own quality assurance process and figure out how much time will be required for the full integration and testing process. It will be harder for creators to push out nightly updates and bug fixes during a festival.

The MOR already has a more permanent line-up of immersive art, and if these ephemeral shows are successful, then there will likely be a number of other museums and digital distribution options that emerge. Right now the Museum of Other Realities is $19.99 on Steam, and there may be additional charges for special events or future time-limited showings of immersive work.

RECREATING THE CULTURE OF IMMERSIVE FESTIVALS WITH SOCIAL VR

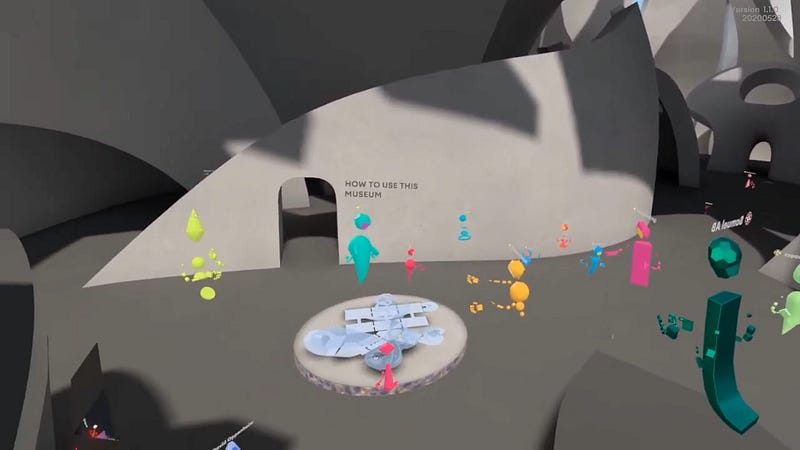

A social

gathering at the entrance of the Museum of Other Realities

A social

gathering at the entrance of the Museum of Other RealitiesIt’s likely that either the MOR or another application will be able to figure out how to properly deliver high-end, immersive art experiences to the comfort of your home. This will start to replicate the experience of seeing all of the selected works, but without the hassle of waiting in lines. You will still have to wait for the download to happen either all at once or for each experience, but the bottleneck will be your internet bandwidth rather than the physical throughput limitations of the festival.

However, there is a risk that a lot of the emergent socializing will be lost, including extended periods of networking. The challenge with virtual conferences so far is that it’s difficult to replicate the same level of time, energy, and focus of traveling when attending a virtual event from home.

The challenge with virtual conferences so far is that it’s difficult to replicate the same level of time, energy, and focus of traveling when attending a virtual event from home.

The current dynamic with virtual gatherings is that attendees tend to drop in and out for shorter periods. Attendees should be able to see all of the content of an immersive festival in 4–5 hours, but this doesn’t solve the matter of socializing. This will only occur when the virtual environments make such socializing not only possible but emphasized as a feature of the gathering.

The MOR has one of the more unique social VR architectures because up to 1,000 people can share the same persistent space. They use Normal VR’s Normcore to automatically scale out the social features of real-time chat into dynamic rooms for spatialized voice chat. People outside of your audio shard are rendered as transparent ghosts, and if you want to speak with someone, then you have to invite them into a shared audio room shard.

The MOR still faces the limitation of 25–50 people in a single audio-sharded room, but this technical architecture of joining shared audio spaces allows for hundreds of people to be roaming around in the same virtual space. Ultimately, the MOR is able to recreate the experience of roaming the hallways of a gathering, which increases the likelihood that you’ll collide with someone you know. I had a lot of really great serendipitous collisions in one of Alex Bowles’ weekly MOR meetups.

I also hope to see official parties with a range of start and stop times specific to two or three timezone regions to accommodate people from around the world. There have been a lot of after-parties at festivals like Sundance and SXSW, and so I’m excited to see the replication of similar parties across the social VR landscape in apps such as VRChat, Rec Room, AltSpace, Neos VR, The Wave XR, or Mozilla Hubs.

The MOR, Oculus TV, and VeeR are the apps that are helping makers distribute some of the first virtual festivals, but there are other social experiments around immersive stories worth checking out.

IN CONCLUSION

Just as there are thousands of museums around the world, over time I expect that there will be more and more virtual galleries, curators, and museums with a wide range of curatorial intentions. This is a rapidly developing story, so there are inevitably existing solutions that I haven’t heard of that are still in the process of emerging. As we attempt to recreate these festivals virtually, I hope to see more experiments that push the boundaries of what’s possible. The pandemic is forcing us to figure out some of the fundamentals around distribution, marketing, and funding that I hope will make the community stronger in the long run.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.