Commodifying and subverting platform data collection in the collaborative immersive online performance “Play4UsNow”

Henry* bent forward and spread his buttocks open with his hands on the lower right corner of my Zoom screen. A techno track played in the background as I spotlighted his video, enlarging it for viewers. The Zoom grid included masked gallery-goers watching from Düsseldorf, Germany, black video-less boxes with names, and eight costumed performers who taunted Henry and some other nude participants on display. A submissive craving humiliation, Henry decided to fulfill his fetish by broadcasting his anus via Play4UsNow, an immersive online performance that I produced with artists Esben Holk and Stephanie Ballantine in November 2019.

The words

“digitalisation,” “submission,” and “domination” are imposed over cutout images of Lena Chen, Esben

Holk, and Stephanie Ballantine dressed in fetish gear, posing nonchalantly. Below their images are

the title “Play 4 Us Now” and tagline “Your Data, New Fetish” of the performance. This graphic is

used as the intro and landing page for the website play4usnow.com.

The words

“digitalisation,” “submission,” and “domination” are imposed over cutout images of Lena Chen, Esben

Holk, and Stephanie Ballantine dressed in fetish gear, posing nonchalantly. Below their images are

the title “Play 4 Us Now” and tagline “Your Data, New Fetish” of the performance. This graphic is

used as the intro and landing page for the website play4usnow.com.Featuring an all-sex worker cast and crew across five timezones, Play4UsNow utilized audience members’ data as a form of intimacy and political critique. In a moment when sex workers face seemingly insurmountable legislative and algorithmic odds, experiencing discrimination on and off-line, we wanted to discover the political limits and possibilities of erotic power exchange. What happens when we imagine sex workers as the digital gatekeepers and subvert the power relationship between sex workers, technology, and audience? Is such exchange a true form of power for the sex worker or does it merely place them in service to an audience’s desire in a different way? What are the implications of placing such exchanges within a public art context versus a purely transactional private one?

Since the 2018 passage of FOSTA-SESTA, online platforms have been steadily banning sexual content in a wave of digital gentrification with devastating consequences for sex workers and erotic content producers. Sex workers have long relied on digital networks for marketing and self-promotion, screening clients, and sharing professional advice. Similar to other stigmatized communities, sex workers also connect with peers online for interpersonal and emotional support when coping with issues like the threat of family disapproval or outing.

Considering the many ways in which sex workers get fucked by the system on a daily basis, we wanted to imagine a speculative world where we are the ones holding power. Within the marketplace of surveillance capitalism, power is data, and data is the 21st century fetish object. Despite a recent iPhone iOS update that automatically opts users out of sharing personal data, Katie Notopoulos writes in Buzzfeed that they choose to continue letting “big daddy capitalism to rawdog [their] data.” As a technology journalist, Notopoulos should know better, and yet, they can’t resist the pull of personalized product recommendations and photos of themselves found through facial recognition. They’re a self-identified “data cuck,” submitting to the algorithm the way that some wish to submit to the stiletto of a latex-clad domme.

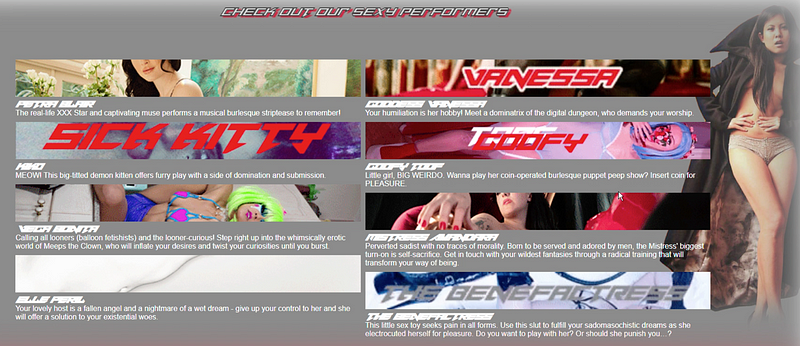

“Check

out our sexy performers”: this screenshot of performer profiles on play4usnow.com displays banner images and short

descriptions of eight performers.

“Check

out our sexy performers”: this screenshot of performer profiles on play4usnow.com displays banner images and short

descriptions of eight performers.Play4UsNow asks viewers to critically consider their own experiences of online surveillance and privacy through “data domination.” Commissioned by the German media arts festival Die Digitale, Play4UsNow was presented through an interactive website and a subsequent live, digital performance broadcasted to online audiences and an in-person exhibition. Recalling a Geocities aesthetic, the website bombards visitors with flashing banner ads for adult services and persistent pop-up windows. In return for engaging with invasive questions about sexual preferences and personal details, the user receives an invitation to a performance in the “data dungeon,” where they are confronted by a group of digital dommes.

Recruited from our social networks and friends, these real-life sex workers have been personally impacted by policies like FOSTA-SESTA. In private breakout rooms, audiences watched the dommes perform pieces ranging from burlesque and clowning to electric stimulation and pet play. Meanwhile, we shared a screen that displayed user’s data and revealed everything from their masturbation habits to the answers to their security questions. I read aloud passages about individual audience members, taunting them with information regurgitated from their encounters with our website.

Play4UsNow did not invent data domination. Rather, this concept has evolved quite naturally from power exchange practices, such as blackmail and financial domination, which push the edge of participants’ psychological limits. For those who fetishize humiliation, having witnesses can be part of the thrill. I have demanded that men kneel before my feet on crowded sidewalks and spat inside of drinks that they consume in upscale bars. But when digital space becomes the public site of a scene, the stakes of humiliation scenarios are invariably raised. With a password in hand, a domme has the power to (consensually) invade someone’s privacy and annihilate their reputation with a single social media post. The risk is the thrill for the submissive; the power is the thrill for the domme.

That power — despite its transient nature — is all the more relevant in an digital landscape hostile to sex workers who are subject to algorithmic discrimination. What this looks like in practice: getting your posting privileges revoked because you used the word “sex” in a caption; no longer showing up in search results for your username; and decreasing follower engagement leading to decreasing economic opportunities during an already-precarious time of pandemic. In their totality, these barriers systematically disadvantage sex workers, whose industry was pivotal to providing the infrastructure and innovations upon which the Internet has been built.

As a political tool, art has the power to reach audiences for whom academic papers, advocacy campaigns, and workshops may not resonate. By virtue of being commissioned for an art festival, Play4UsNow was positioned as a work of art, yet it was also accessible to anyone online interested in browsing our website and willing to “pay” with their data for entry to the performance. While some audience members were, in fact, an art-going public (e.g. those who attended the in-person exhibition), others were curious onlookers, and yet another group consisted of seasoned submissives eager to be humiliated before virtual strangers. But despite our disparate motivations for being involved in Play4UsNow, what we all shared in common was our reliance on technology that persistently follows us as we follow each other. Our clicks, keystrokes, and scrolls generate commodifiable information about who we are, and even when we don’t entirely consent to the terms of the arrangement, we may even enjoy the targeted advertisements that appear alongside suggestions for people we might want to follow.

A few hours after the performance, I received a DM on Instagram from Henry. “I was on such a dopamine rush that I didn’t weigh out the consequences. I’m so ashamed of myself. Are you sure I didn’t show anything that exposes me as a person in this Zoom call?” As is common with BDSM, Henry was feeling the comedown after an intense scene and hadn’t received proper aftercare from the domme who had invited him. I spoke to him about his concerns and suggested that he take a warm bath. He calmed down after I assured him that I didn’t recall his face being visible and that I’m not interested in exposing people who don’t want to be exposed. As much as I enjoyed the power temporarily granted to me by Henry and the other submissives, that power comes with trust and boundaries. And unlike Facebook, I cared about their privacy.

*name has been changed for privacy

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.