Speculative interfaces, future phobias, superpowers and the miraculous

This is number 2 in a series of posts that is part of a one-year research track called Our Brave New World, produced in the context of the Creative Economy theme of the Fontys University of Applied Sciences in Eindhoven, and in collaboration with the Amsterdam based design studio ARK .

Walking

Agents, Laura McCarthy (STRP 2019): Smart pillows with integrated intelligence serving as a

guide, mentor, and carer while you drift away between consciousness and subconsciousness.

Walking

Agents, Laura McCarthy (STRP 2019): Smart pillows with integrated intelligence serving as a

guide, mentor, and carer while you drift away between consciousness and subconsciousness.

Who is in charge?

We become what we behold. We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us.

― quote by Marshall McLuhan (or was it Winston Churchill? Robert Flaherty? Emerson Brown? John Culkin? William J. Mitchell? Anonymous?)

With the Canadian philosopher and media theorist Marshall McLuhan in mind — a man who was described as “the hottest academic property around” by the San Francisco Chronicle after publishing the Gutenberg Galaxy (1962) and Understanding Media (1964) — we can say that technology is not just about technology but mainly about us, the users, and the world we live in.

Technology is key to our being as humankind and distinguishes us from the world of animals: we design our own tools. Or, even, as philosopher Peter Paul Verbeek explained, we see humans as animals with something extra, with language or with reason. But the French philosopher Bernard Stiegler talks about default, an animal with something missing: We don’t have sharp claws that help us to survive, or a rock hard shell, so we need an add-on — fire, tools. And these tools become extensions of ourselves. From the hammer and nail, to the printing press, airplanes, and the internet — they all enhance our powers, share our words and thoughts, are our wings, our brain and memories, and our eyes.

However, with the rise of artificial intelligence and machine learning, technology becomes more and more complex and leaves many of us guessing about what’s going on.

NFF

2018. Keiichi Matsuda showing the work he is developing for Leap Motion

NFF

2018. Keiichi Matsuda showing the work he is developing for Leap MotionThis is especially poignant because technology has a formative, and at times disruptive, impact on who we are and what we are. In the never-ending — or might we say classic — discussion between the technological determinists and the social constructivists, we are still trying to decide who is taking the lead in this world: we as humankind, or technology itself. Do we design and construct our tools at a conscious level, or are we mere pliable users of the tools we have created? Did we think, “Hell yes, let’s make a device that has us scrolling for hours on end to see what our exes, old classmates and strangers are up to!” Or did we just happen to end up at this point, wondering, “How on Earth did we get here?”

The only chance we have to actually take control of the technologies that shape our world and to democratize their development is to pay attention to their course. Not just the nerds and techies should have a say, but we as users, citizens, artists, fans, and thinkers should also be able to chime in. A social construction of technology is only social if we all take part.

Within the ecosystem of creative economies, festivals play the role of labs, and have an important task in facilitating this discussion. They are the main stage in a process of communication, providing a venue for the act of deciphering and decoding meaning. In this process, festivals afford a common ground for the exchange of ideas and reflection, and as spaces of experimentation. Through careful curation and contextualization, they demonstrate tangibly what new technologies are capable of, and what they might mean for us now and in the future.

The curator as caretaker of the soul

As Roya Rastegar explains in her essay “Seeing differently: the curatorial potential of film festival programming,” the original meaning of the word curating comes from the Latin word for to care: “In the 18th century a curate was a cleric, a spiritual guide responsible for the care of souls.” Today in the context of a museum or gallery, or indeed of a festival, the role of the curator is to present the art and the artist’s vision to collectors, audiences and artists, “to build the framework in which audiences see and engage with artworks in such a way that can resonate within broader cultural, political, and social contexts.”

Curators not only take this role very seriously, but also approach it competitively. They carefully construct themes for their programs to proclaim their identity as an organization, and use this as a mode of distinction. They use themes to impart their vision of the possible ramifications, hairy objects or other contingencies in our world to come.

Festivals exist in the sweet spot

You could say that festivals are the sweet spot of the creative industries: they are the place where audiences can touch, feel and try new technologies, where makers meet and critics encounter works for the first time. Together they trace new possibilities and exchange ideas.

This means that we can see festivals as labs: new technologies and their consequences are being tested and explored through artistic mediation. They do this in many different ways: They commission new works where specific technologies, tools and developers are being put together for the occasion. There are talks, exhibitions with films, VR, installations and performances. On several occasions festivals have also introduced and fostered knowledge exchange and collaborations between the artistic field and the commercial tech world, as we for example can read in Caitlin Burns’ and Brian Seth Hurst’s post in this issue about emerging technologies and festivals.

Festivals also function as a pressure cooker for ideas. They organize workshops, masterclasses and talent programs where new projects are being developed: Many projects travel from festival to festival, making iterations on each occasion, and accordingly slowly finding a new form and mode of expression.

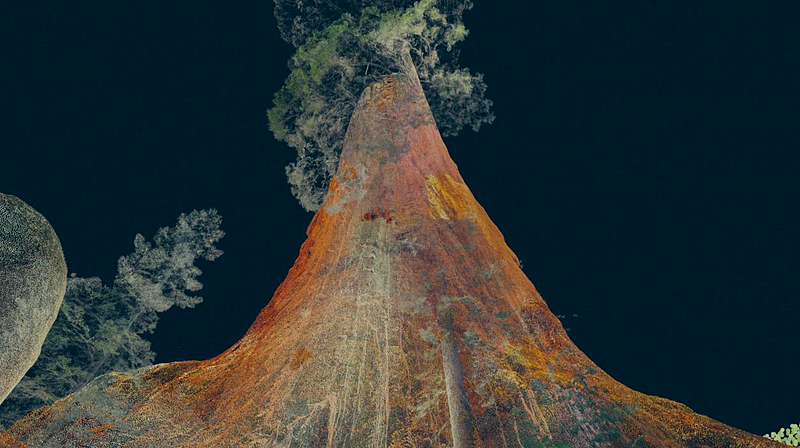

Treehugger, Marshmallow Laser

Feast 2017

Treehugger, Marshmallow Laser

Feast 2017A good example of these kinds of developments is the work Treehugger by artist collective Marshmallow Laser Feast, originally commissioned by Cinekid MediaLab (Amsterdam), STRP (Eindhoven), Southbank Center (London) and Migrations (North Wales). After iterations in each location, the work eventually won the 2017 Tribeca Storyscapes Award in New York. Treehugger is for Marshmallow Laser Feast an important step in their development as a company, both artistically and technically, and simultaneously raises the bar for the field at large.

Besides the fact that festivals just show us beautiful stuff, amazing landscapes, and intriguing interactions, they also help us to get beyond the black box of technology, and to place ourselves within the stalemate between technological deterministic or social constructivist — or to question it altogether. They are flexible and can respond to fluid trends, hypes, and sentiments. They keep track of the industry, society and art in such a way that they make it accessible to a general audience, and at the same time, they show us how to live and be human in this world that we are creating and inhabiting together.

Here is a look at how several festivals are doing so.

IMPAKT

IMPAKT

program: Masque by Xin Liu (Photo: Xin Liu, Hongxin Zhang) as a psychoacoustic system that

manipulates perception in order to cause bias in experiences.

IMPAKT

program: Masque by Xin Liu (Photo: Xin Liu, Hongxin Zhang) as a psychoacoustic system that

manipulates perception in order to cause bias in experiences.A good example of a festival that shows the relationship between technology and society is IMPAKT, a Utrecht-based organization and festival that presents critical and creative views on today’s culture in a truly interdisciplinary context.

IMPAKT embraces a broad spectrum of disciplines. They trace the impact of technology, and we know today this is felt almost everywhere: in the arts, but also in society at large, in academia, media, science, journalism and politics. And they do so with as many people as possible. All through the year, the curators share their programme concepts with a diverse audience and invite them to respond. In this way, they spark and foster a discussion that goes beyond the regular festival grounds, while creating a local and international community of stakeholders.

Another way IMPAKT keeps their flexibility is that they work with guest-curators. This year, it’s the turn of Jan Adriaans, Barbara Perea, and Marloes de Valk. Together they have developed the theme Speculative Interfaces, focusing on how the interface actually functions as an intermediate between us and technology. They are looking into the new opportunities that technological advances will present: How will we respond when the future interface is increasingly integrated into our bodies? Will it eventually physically merge with us? Who is controlling who? What would this mean for our autonomy and privacy? These kinds of questions spark a conscious reflection on one’s own perception of technology.

This year, the festival runs from October 20 to December 1.

STRP

Sense of Gravity, Teun

Vonk@STRP (2019). The installations explore how the body reacts to the visual, tactile and

bodily sensations when gravity is defeated.

Sense of Gravity, Teun

Vonk@STRP (2019). The installations explore how the body reacts to the visual, tactile and

bodily sensations when gravity is defeated.STRP is is also dealing with the theme of technology and society. This Eindhoven based international festival, running next year from April 2–5 in Eindhoven, is known for its international collaborations and commissions. In the industrial Klokgebouw in Eindhoven, a former Philips building, they organize conferences, talks, expert sessions, workshops for kids and adults, concerts, and performances.

The festival takes on a specifically optimistic approach towards this technology debate, and wants to know how we can resist the demands technology seems to make of our society. In 2019 and 2020 they do this with their slogan “To hell with future phobia, here’s to the future” Under this motto, the festival wants to escape the contemporary undercurrent that seems to be led by a crippling nostalgia about how everything was better yesterday.

In this way the organizers want tododge the dystopian fantasies of future technologies by focusing on the humane, poetic, and soft side of technology. Technology itself is thus pushed into the background and the aim is to promote artistic expressiveness and social relevance.

A clear expression of this attitude is the immersive installation of Teun Vonk, A Sense of Gravity, which premiered at the festival in spring this year. In his work Vonk focuses on the human body, and how we cope with an even more technological future. His prediction is that the level of digitization and automation will only increase, and that the relationship between humans and machines, and the way we think about this, will change significantly. In A Sense of Gravity, Vonk gives the audience a chance to be released from the forces of gravity for a short moment, while being immersed in a one-person experience, elevated and surrounded by an unfolding spiraling shape.

Todays Art

Pia Klemp and Srećko

Horvat taliking about “fortress Europe” during TodaysArt.

Pia Klemp and Srećko

Horvat taliking about “fortress Europe” during TodaysArt.TodaysArt , an annual event held in September in The Hague, shows visually immersive art and music, performances and organizes talks. They celebrate technology in its digital and physical forms but also critically observe more social and political aspects. Over the past two years the festival has been zooming in on the concept of the algorithm hidden deep within our digital “parallel world”: invisible at the surface, but unavoidably steering our daily reality.

This year they addressed their program through the topic of CONSCIOUSNESS, and — inspired by their keynote speaker Douglas Rushkoff, who warns us about platforms like Facebook (Watch out, we are not the users, we are used) — they focused on the role of “Team Human” .

At first sight, TodaysArt seems to explore mostly the new aesthetics of the digital world, and celebrates the crossroads of music and visual culture in a raving nightlife. However, they also talk about digital and high-tech cuisine, blockchain and biotechnology. And, for example, this year they also gave the floor to political discussions, such as the conversation between the Sea Shepherd captain, animal and human rights activist and author from Germany Pia Klemp and Srećko Horvat, the Croatian philosopher, author and political activist, who talked about the refugee crises, globalism, and the alleged demise of the European dream.

Manifestations

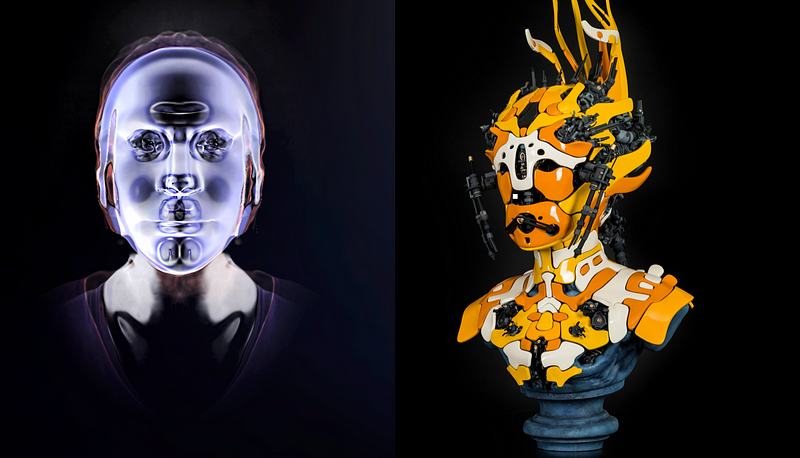

Manifestations 2019: Left: Ningli Zhu, Face to Face and right: Nick Ervinck,

Nesurak

Manifestations 2019: Left: Ningli Zhu, Face to Face and right: Nick Ervinck,

NesurakAnother player in this technology-society discussion, also based in Eindhoven, is Manifestations, taking place this year from October 19–27. The question that takes the lead in their programme is “Will the Future Design Us?” Creative director Viola van Alphen observes that technological innovation has a growing impact on our daily lives, our societies, and our humanity, and this is the main motivation for the program. Van Alphen expressly raises the question as to who or what all this technology ultimately is serving. Is everyone able to participate? Are these developments beneficial and healthy for all of us? What role do we actually want technology to play in our lives?

For Manifestations it is the artists who are most able to put technology and unstoppable developments in a different, unexpected perspective. This year the theme of Manifestations is “Superpowers: moving from paranoia to empowerment.” They approach technology not as profit-driven solutions for the convenience of the individual; instead they research, play, ask, and show how technology can help to build a kinder, more humane world. Technology gives humanity superpowers and the sky is the limit when it comes to shaping our bodies, the earth, and our minds. But will we all have superpowers and super beauty, or will that only be for the happy few?

The show this year will address a range of issues, including body enhancements, Mother Earth, being perfect, fear, hope, mass media, robots, e-fashion, and macho versus feminine and shows the work of mostly young, recently graduated artists. Next to this, there are kids’ workshops, lectures, and meet-ups. Manifestations focuses on “nicer, more human technology (…) innovations that everyone benefits from, young or old, male or female, rich or poor.”

Nederlands Film Festival

Sacred Hill, Ali Eslami,

Klasien van de Zandschulp and Mamali Shafahi about how to be human in VR picture credits:

Anita Bharos, LAB8WORKS

Sacred Hill, Ali Eslami,

Klasien van de Zandschulp and Mamali Shafahi about how to be human in VR picture credits:

Anita Bharos, LAB8WORKSAnother trend we can observe is the role film festivals play in the art, science and technology debate. Programs such as Sundance’s New Frontier, Tribeca’s StoryScape, Venice ‘s VR Island, and IDFA’s Doclab run programs dedicated to new technologies. They all show a wide range of works in which storytellers, creative technologists, filmmakers, and coders work together to tell different narratives.

The Nederlands Film Festival, in 2019 running from September 27 - October 5— and for which I am curating the Interactive program — is also moving in this direction and explores themes that question the status of technology. This year the program is wrapped around the theme of Lab Life: In Search of the Miraculous. This program makes space for the contemporary notion that because of the growing complexity of technologies, multidisciplinary teams are necessary. Co-creation and collaboration are shifting the focus from single authorship.

Within this theme, the Nederlands Film Festival has several exhibitions, an award show for interactive productions, workshops and expert meetings, and adds the interactive approach into the mix of the more traditional film and television conference. The festival wants to raise awareness on both sides of the fence: they want to inspire traditional filmmakers to take note of what is happening in the interactive world but also the other way around. They aim at solid collaborations between the different worlds and intend to explore how professionals from the two fields can strengthen each other’s domains.

As an example of this practice, Sacred Hill, an interactive VR performance about what it means to be human in virtual reality, has been commissioned by the festival in collaboration with The New Institute. Here the engineer Ali Eslami, the artist Mamali Shafahi, and designer and artist Klasien van de Zandschulp have collaborated on a work that investigates what it means to be human in VR.

In my post next month, Sacred Hill will be explored in more detail.

How to be human

Festivals with their programs, labs, themes and commissions, and the creative industries at large, arguably are still doing the same thing McLuhan tried to explain in his famous Playboy interview back in 1969:

PLAYBOY: To borrow Henry Gibson’s oft-repeated one-line poem on Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In — “Marshall McLuhan, what are you doin’?”

McLUHAN: Sometimes I wonder. I’m making explorations. I don’t know where they’re going to take me. My work is designed for the pragmatic purpose of trying to understand our technological environment and its psychic and social consequences.

As far as I am concerned, this is still necessary and these efforts still make sense. Technology is pointing us again and again toward the same question: what does it mean to be human? In this technology-driven society, festivals are helping us to make sense of the latest tools and features. With their themes they frame our gaze and contextualize our experiences. They all in some ways deal with the reciprocal relationship between us as “team human,” technology, Mother Earth and the future. The themes function as a lens and is a suggestion as to how we can look at the topics, discourses, and works they show us. They try to make a point about our world. Or basically, what it means for us to be human in this world. And it gives us these common grounds to reflect on the now, premediate the future, and discuss its course.

Next month’s post will be a close reading of the speculative, futuristic, performance-VR piece Sacred Hill by Ali Eslami, Klasien van de Zandschulp, and Mamali Shafahi, about how to be a spiritual being in a digital reality.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.