A festival dispatch covering the INTER:ACTIVE symposium and exhibition

CPH:DOX was the first international film festival to pivot online in March 2020. Last month, to widespread relief, it finally returned to cinemas and exhibition spaces across Copenhagen — but with one big difference. A silver lining of its two years online was that it also became accessible to audiences across Denmark: the 2020 festival reached over 100,000 viewers, many of whom would not have had the chance to engage with it in person. Keen to hold on to this accessibility win, this year CPH:DOX returned as a hybrid festival.

The festival’s hybridity extended across its film program, public events and conference, industry pitching forum, and INTER:ACTIVE symposium, which this year was subtitled “The Future Belongs to Those Who Can Hear It Coming: An Inquiry Into The Future of the XR Industry.” The symposium was both live and livestreamed, with a multi-camera setup and clear audio, and also quickly made available to view on demand. After two years of enforced online attendance, the proliferation of options for how to engage with the event provided an interesting challenge for in-person attendees: should we physically attend the entire symposium, drop in on selected presentations and skim through the rest later, or just watch the whole thing in our hotel rooms and then come out for the party?

The challenge of how to be hybrid also formed a theme for the day’s discussions. Various presentations engaged with the shift to hybrid working practices accelerated by the pandemic, and with the potential for XR to become a space within which the immersive nonfiction community works as well as an outcome of this work. For example, Annette Mees asked, “When do we need to be physically together, and how best do we connect when we’re physically apart?” A pertinent question, considering how small but geographically widely spread the immersive nonfiction community is.

More interesting to me, however, was another question, asked by Vassiliki Khonsari: “Is it limiting for XR to be associated with film festivals?” It felt strange that such a question should be asked at a film festival. It felt as if a sub-text had inadvertently surfaced — as if, below its seeming self-confidence (“do we need to be here?”) another question was also being asked: “what are we doing here?” On the one hand, it is heartening that ever more film festivals are engaging with emergent technologies and welcoming the immersive community. On the other hand, it was impossible not to notice that at the same time that this small group of immersive creators was having its symposium, a far larger group of film producers and distributors was doing the real business of the festival outside. Khonsari’s question touched on a deeper uncertainty about how nonfiction XR defines itself in relation to the various distinct (and much better established) ecosystems it touches — notably documentary, art, and gaming. One could argue that XR visits each of these spaces without fully inhabiting them. “Where,” Khonsari’s question seemed to be asking, “do we belong?”

The

Memor: Eternal Return. Still courtesy of CPH:DOX

The

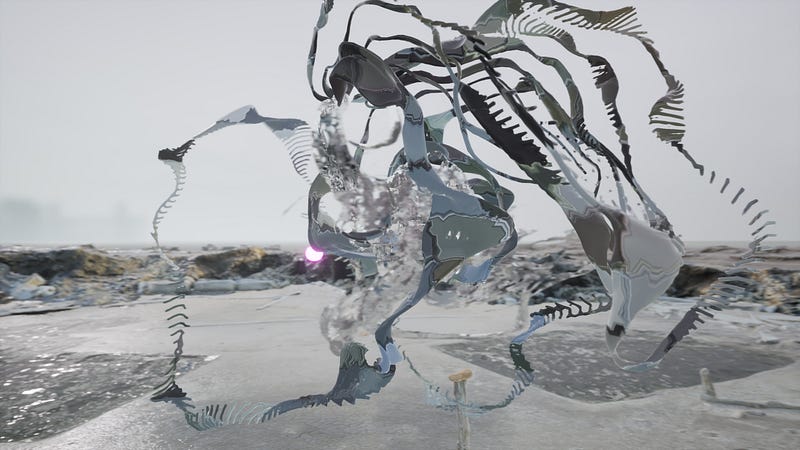

Memor: Eternal Return. Still courtesy of CPH:DOXAs if in response, this year’s INTER:ACTIVE exhibition, emphatically situated within visual art. Curator Mark Atkin’s strategy was to gather a relatively limited number of works, so as to give visitors the experience of a carefully curated art exhibition. Atkin called this year’s program “unfinished business,” and in one work this was literally the case; The Memor: Eternal Return (Lundahl & Seitl / ScanLAB Projects Sweden, United Kingdom, 2019) had already been packed up and was ready to ship to the 2020 festival when the Danish borders closed.

The resulting exhibition fitted with both its surroundings, the 17th century Kunsthal Charlottenborg, and the strong focus of CPH:DOX on artists’ moving image. In one sense, CPH:DOX INTER:ACTIVE 2022 felt like an art exhibition from the future — a seamlessly hybrid gallery space in which physical artefacts are no longer artworks in themselves, mounted on plinths to be admired, but rather tools for physical engagement with digital spaces and constituents of rich media artworks.

This hybridity was most palpable in The Memor: Eternal Return, a combination of VR experience and one-on-one performance. At various times, the participant was invited to touch various artifacts within the virtual space. These corresponded spatially to 3D printed shapes mounted on stands in the gallery, providing the virtual archive with a tactile dimension. Particularly powerful were the subtly choreographed moments of touch between participant and performer. In this perhaps-almost-post-pandemic context, as I found myself touching a stranger palm-to-palm, I felt the resonance of multiple connections overlaid: between myself and the performer, between physical space and digital space, and between my present COVID-aware self and my previous, less circumspect way of being.

Liminal Lands. Courtesy of the artist

Liminal Lands. Courtesy of the artistIn line with Atkin’s aim, most works in the exhibition felt closer to digital art than nonfiction storytelling. For example, Liminal Lands (Jakob Kudsk Steensen; France, Denmark, United States, 2021) was a spectacularly rendered process of continual transformation from one stylized digital/natural landscape to another. Sundance favorite Gondwana (Ben Joseph Andrews, Australia) accelerated years of environmental degradation in the Daintree Rainforest into hours.

Most immediately impactful was the “participatory installation” Captured (Hanna Haaslahti, Finland / Germany), in which visitors’ faces were scanned and then mapped onto the virtual bodies of a crowd carrying out an endless generative cycle of mob-like behavior. Haaslahti’s large-screen installation was craftily located at the entrance of the exhibition, and so formed a recurrent and unavoidable element of the exhibition experience: over an hour after I tried it out, my virtual double was still getting trampled by a crowd of other gallery visitors.

Sometimes, however, rather than providing a foretaste of the future, the exhibition felt more like a flashback to the pre-pandemic past. Time and again, it reminded me of the sensory overstimulation of previous visits to festival-based interactive exhibitions (the multiplicity of screens, the mixing of sounds, the tangle of movement), as well as the sheer Panopticism of it all. In one installation, as I flapped my arms around in the hope of triggering some interaction, not quite knowing what I should be doing, I pictured my ignorance displayed in real-time to passers-by on a nearby screen.

Captured. Courtesy of CPH:DOX

Captured. Courtesy of CPH:DOXVisiting an immersive exhibition in which none of the works were available to experience online similarly felt like a partial return to the pre-pandemic past. CPH:DOX INTER:ACTIVE had a remarkable online program last year built around ‘live documentary’, which brilliantly showcased the potential of livestreaming as a filmmaking tool: it touched on possibilities that may still take years to work through. So it’s completely understandable that this year Atkin’s curation should celebrate the kinds of in-person experiences that were for so long unavailable. But the absence of an online immersive program was also slightly surprising, both in the context of other festivals’ recent immersive offerings (for example, IDFA, Sundance, and SXSW), and of the strong accessibility ethos at CPH:DOX. Hundreds of thousands of viewers across Denmark watched the festival’s film program. But how many people not already connected to the festival would dare to walk through the courtyards of this baroque gallery, up four flights of stairs, and through the clusters of industry power brokers, to try out this exhibition?

One lesson from the last two years is that hybridity transcends residual binaries. Art can be physical, digital, or both together; it can be created and experienced in public and in private — inside, outside, and online. There is no zero sum game here: each is just an extra route to connecting with users. However, it often feels that the creative XR industry still in some ways suffers from teenage identity anxieties. Is it art, or is it tech? Is it in-person or online? Is it good at telling stories, or creating experiences? After two days immersed in the CPH:DOX INTER:ACTIVE program, I wonder whether “the future of the XR industry” is not one future but a multiplicity of futures. And whether, rather than being a weakness, XR’s fluid identity and inherent hybridity could in fact become a unique strength.

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and Dot Connector Studio, and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.