Insights from two panels interrogating definitions of the metaverse and preconditions for artistic flourishing within it

In Neal Stephenson’s dystopian novel Snow Crash, which takes place in the aftermath of a worldwide economic collapse, the metaverse was a parallel virtual world only accessible to the techno-elite. People escape from their harsh reality to the metaverse by wearing goggles and earphones and appear as their own customized avatar. Sounds familiar? This metaverse was overrun with corporate advertising. Stephenson was warning how massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) worlds could evolve.

During the Double Exposure Investigative Film Festival & Symposium in October 2021, the MIT Open Documentary Lab and Immerse partnered to present two panels titled “Making the Metaverse,” after this current issue’s theme.

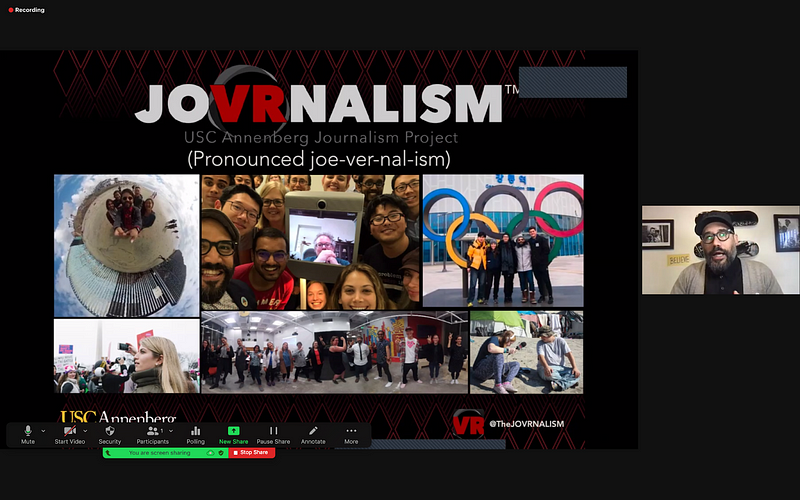

The first panel, “Case Studies,” moderated by Immerse editor Abby Sun, featured three pioneering makers describing their latest projects. Sparsh Ahuja presented on Project Dastaan’s outreach activities, reconnecting 1947 India-Pakistan Partition migrants to their ancestral homes via 360 VR. Violeta Ayala showcased her Cryptovoxels digital gallery, where her collective, KOA.xyz, exhibits information about their projects, including the VR animation Prison X. Lastly, Robert Hernandez, shared his project Jovrnalism, which uses emerging technologies to produce digital journalism with his students at USC Annenberg. This dialogue set up the ground for the following panel.

Immerse Editor Abby Sun

introducing “Making the Metaverse, Part 1: Case Studies.” Panelists, clockwise from top right:

Robert Hernandez, Violeta Ayala, and Sparsh Ahuja. Screenshot courtesy of writer.

Immerse Editor Abby Sun

introducing “Making the Metaverse, Part 1: Case Studies.” Panelists, clockwise from top right:

Robert Hernandez, Violeta Ayala, and Sparsh Ahuja. Screenshot courtesy of writer.Moderated by Sarah Wolozin, Director of MIT Open Documentary Lab and a part of the Immerse editorial collective, the second panel brought together writers and journalists who provided insights into what is at stake within current debates on the metaverse and tried to make sense of our present locus. The panelists included Jesse Damiani, a writer who talked about the potential for journalists to cover this new space; Kathryn Karaoglu Hamilton, who addressed questions of control, representation, and access; and Andrew Wang, who shared his experience building community within the NFT’s ecosystem.

MIT Open DocLab Director Sarah

Wolozin moderating “Making the Metaverse, Part 2: Reimagining the Present.” Panelists, clockwise

from top right: Jesse Damiani, Kathryn Karaoglu Hamilton, and Andrew Wang. Screenshot courtesy of

writer.

MIT Open DocLab Director Sarah

Wolozin moderating “Making the Metaverse, Part 2: Reimagining the Present.” Panelists, clockwise

from top right: Jesse Damiani, Kathryn Karaoglu Hamilton, and Andrew Wang. Screenshot courtesy of

writer.Here are three takeaways that were shared between the two panels.

1. The metaverse is a slippery term.

Sarah Wolozin: The metaverse is hard to define. If you ask fifty people, you might get fifty definitions. It’s about virtual worlds, VR, AR, gaming and the interplay between virtual and physical worlds. Moreover, it’s about new decentralized financial ownership systems, blockchain, new identities, and new communities.

Abby Sun: In the technology-oriented point of view, the priority is on identities, avatars, objects, history and payments moving freely, but what about the movement of people, of memory, of dignity, and of time?

Jesse Damiani: It is like a wave. It’s moving, it’s evolving, and will be a tsunami.

Violeta Ayala: I’m going to define the metaverse the way I want to define it, and it will be a place where I can protest and where I can express my ideas.

2. Accessibility and inclusion are crucial: creators can hijack Big Tech tools. But the panelists disagreed about the conditions needed for their art, filmmaking, and journalism to flourish in this space.

Robert Hernandez: We found that what was really powerful is democratizing this technology [Snapchat Lens Studio] that is often held by companies with big resources and are viewed with corporate dollar signs, and we want to make sure that our diverse voices are included in that reality.

Violeta Ayala: If I want to share my trailer with someone, I just give them the exact coordinates [for the Cryptovoxels gallery] and they can click on the trailer. It has a real 3D representation and you can watch it and feel like you are sitting in a place. Audiences can understand a little bit more where I’m coming from, and how we create all the projects and characters.

Sparsh Ahuja: [I care about] the extent to which one of the digital assets can be experienced without the individual user having to own a particular device. They could be projected onto public spaces without necessarily needing a headset or needing this specific phone or a specific bit of software. I think that’s the challenge of democratization — not everyone has a headset. So can we make the metaverse in a way that the individual user doesn’t need to actually own it?

Robert Hernandez: My framework is how affordable and accessible it is. Who can buy this software? How can I get a free or cheap version of it? And when I create something there, can I download it and put it into my own website or my own production platform?

Violeta Ayala: For me decentralization is the future. Within a decentralized world, I am very hopeful.

3. A diversity of voices and stories about the metaverse are indispensable. Who and what are missing?

Jesse Damiani: There is a need for different kinds of stories to be told about the metaverse. There’s a lot of technology, both from the hardware and software perspective, such as cloud infrastructure. I also think that it’s important to start to reframe how we think about the metaverse as a human-first thing. Eventually, in some future ideal, non-human and post-human entities might coexist in those spaces with us.

Kathryn Karaoglu Hamilton: I think Jesse is totally right that we need to have different kinds of stories being told. It’s not a tech story, it’s a culture story. But the people telling it are mostly tech journalists. How do we allow different people, from anthropologists to social critics, access to this space? Otherwise the stories are going to continue to be kind of cringey, because they will come from a single point of view. The demographic in the space is majority white, English-speaking men from Western Europe and the US. What is the technological barrier to entry for hacking and glitch in this space? Is the technological barrier to entry so high that we, the majority of people, will become consumers in a very superficial way rather than actually being able to access the underlying structures of this space?

Andrew Wang: The idea of yearning for the vast and endless sea is what the metaverse feels like right now. I think we still have a long way to go but it’s community-building on this drive to make a better society where people who have been on the margins can finally be centered. We have a chance to do this and do this right.

Robert Hernandez presenting on

JOVRNALISM. Screenshot courtesy of the writer.

Robert Hernandez presenting on

JOVRNALISM. Screenshot courtesy of the writer.Looking ahead

Regardless of whether we are champions or skeptics of the metaverse, it is happening. When Wolozin asked the panelist about the role of journalists and nonfiction storytellers in this emerging land, Damiani expressed that he has noticed a “knee-jerk reaction [from writers] to just disregard it because it’s part of this frothy hype space.”

He believes this is a missed opportunity because “this metaverse discussion is an occasion for sense-making and storytelling, which is what journalists and documentarians can uniquely do… Let’s bring up those critical questions, let’s try to understand those social communities.” Instead of trying to define the metaverse, Damiani encourages us to start making sense of “this messy moving collective experiment that’s occurring in real time.”

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and Dot Connector Studio, and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.