Models of Sustainability for Immersive Media

When I think about models of sustainability in immersive media, the image of tectonic plates come to mind: the people who survive have to stand and balance while the plates shift underneath them.

Four months after I first presented this research at CPH: Dox, we still don’t have the answers. But there has been a lot of experimenting and acceptance of a new normal. Kent Bye wrote an excellent article about how festivals are adapting. VR headset hygiene, protocols and products have also emerged.

The documentarians, artists, journalists, and curators I interviewed are working at the cusp of emerging media. They’re used to a constantly changing landscape—although not a pandemic! More than many, they are equipped to adapt. This ability is the model of sustainability. But no matter how resilient they may be, there needs to be a solid plate under them so that they can do their work.

How do we support them so that they can push boundaries, establish more equitable practices, question existing models, and work outside of established norms? This article dives into ways people are trying to sustain themselves and what still needs to happen.

Immersive media is highly interdisciplinary and makers navigate many different fields from theater to art to film while also navigating a newly emerging but fragile XR ecosystem.

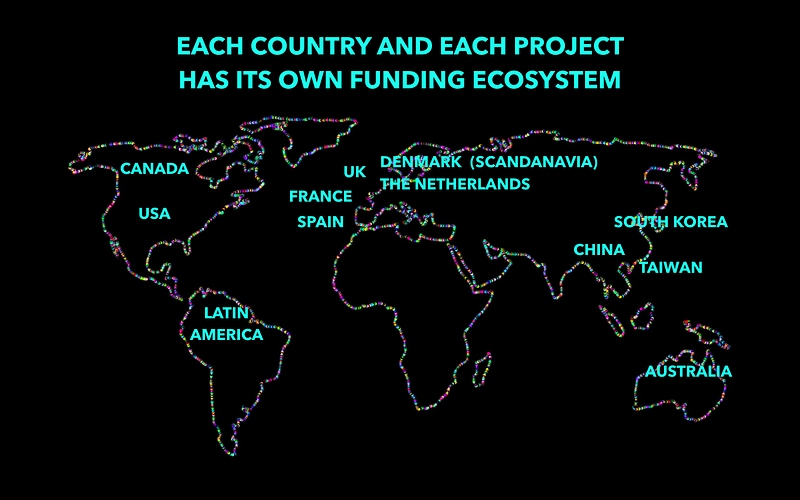

I interviewed people from the United States, Canada, and Europe, but artists in Asia—in particular China, Taiwan, and South Korea—are starting to gain attention in the West. Australia too has a growing immersive media sector.

Each country and project has its own funding ecosystem and Canada, the US, England, and France produce the most. Overall, the countries with the most government backing fare best. Governments in Europe and Canada have invested considerably in immersive digital media both through their cultural funds and creative economy funds as well as regional funds and tax incentives. Research funding for university-industry partnerships is also an important source.

The US government provides considerably less funding and the first wave of VR was supported by technology companies looking for content to sell their hardware. This funding has mostly dried up. Foundations such as Knight, MacArthur, and Ford also support the field. Universities are becoming an important space for R&D, incubation and production, and they are providing much-needed research on best practices, potential use cases, and impact.

It’s difficult for Americans to sustain their work but some people I interviewed were optimistic about wider adoption of VR headsets. The field is young.

People employ a host of different strategies to stay afloat. This is a list of some of these strategies and I’ll go more deeply into these strategies in three case studies.

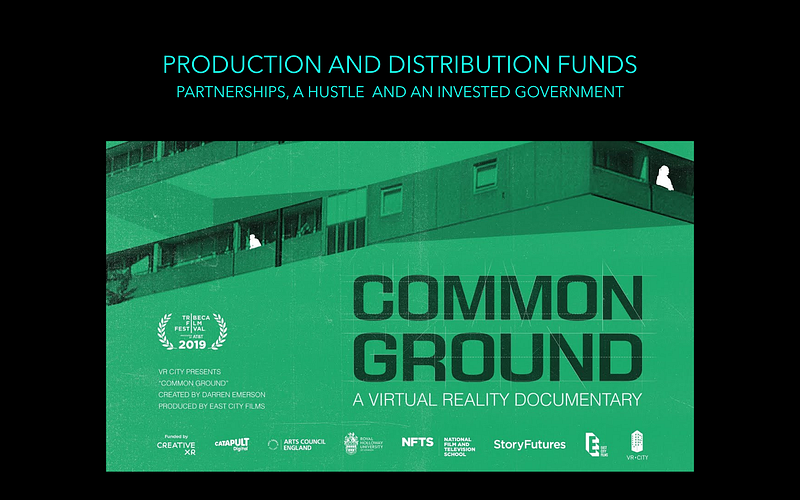

CASE STUDY 1: A Documentarian in England—Darren Emerson

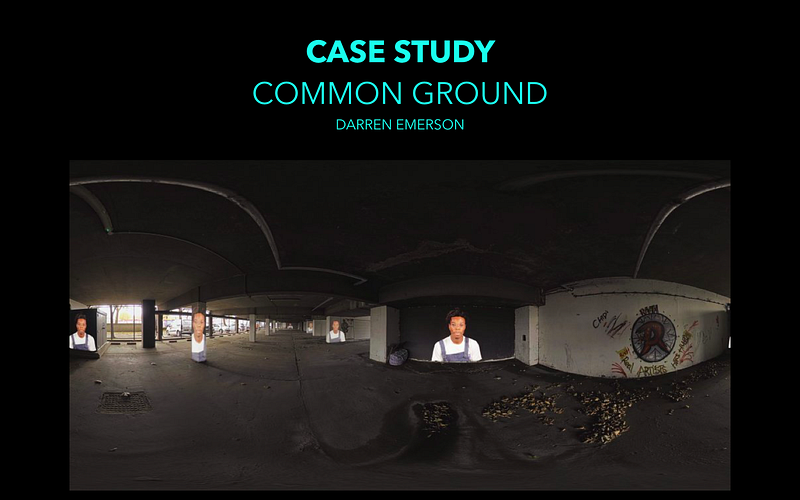

Common Ground is a VR documentary that mixes archives, 360 video, photogrammetry, AR, and interaction to create an embodied cinematic form within the documentary tradition.

Darren Emerson found that his skills as a documentarian were transferable to 360 video. He created his first 360 video, Witness 360:7/7, about a woman’s experience of a UK bombing, without external funding. He received a small amount of funding (5k) from Sheffield Film Festival for his second project, Indefinite, about the UK detention system.

“We weren’t really in the world where we were getting grants or funding for original commissioned work,” Emerson said. “That was something I’d always wanted to do, so it was around that time when I started to think about Common Ground that I kind of said to myself, I’m going to figure out how this works. It might take a couple of years, but I hope, by the end of that, I’ll be in a better place to get funding for the work that I want to do.”

Common Ground explores the social housing experiment in 1963 in London called Aylesbury Estate, where thousands of Londoners live now. It’s currently being regenerated and causing significant controversy because of how it’s being planned and its potential impact on residents who will be priced out. Emerson hopes it will help people better understand what residents call their home.

Common Ground is firmly steeped in documentary practice and so it makes a good jumping off point to explore documentary in the context of emerging technologies. Emerson uses the affordances of VR to let the audience feel like they are wandering around the space and he uses AR to let audiences explore the rich archives of Aylesbury Estate in the virtual estate itself.

Emerson described his funders as partners. England now includes immersive media in its funds earmarked for culture, creative economies, and innovation/research, which Emerson was able to access.

Government support is essential to his fundraising strategy, which is not unlike traditional documentary fundraising paths.

But what is notable is that he received funding from the British Film Institute Audience Fund for R&D of a distribution plan rather than a distribution plan itself. Having a distribution plan is key to sustainability. Because immersive media do not have a clear, tried and true method of distribution, it becomes necessary to fund the research of one before it is created.

Scatter Studio Creative Director Yasmin Elayat also talked about the importance of distribution strategies in her own work: “Every project has a budget for [distribution]. Even if we’re not raising it, we’re not going in blindly. [We know] this is what it would take to get this out the door and this is the plan.” She spent months on a distribution strategy for Zero Days and worked with a collaborator to figure out price points. Oculus, one of the funders, originally required Zero Days to be free. Elayat did research, watched different models, and came up with a price point.

Case Study 2: A Collective of Creatives—Marshmallow Laser Feast

Marshmallow Laser Feast is a London-based collective of virtual reality creators. They have a robust model of sustainability, which includes what executive producer Nell Whitley calls a “blended approach.” Whitley explained that they blended learnings or tools from previous projects to the next projects, blended platforms, and blended funders. She says it’s a lot of work because they not only produce their projects but they handle distribution and exhibition — roles that are farmed out to other companies in more established media ecosystems.

Their first VR project, In the Eyes of the Animal, used a technique called “lidar scanning” to capture the bottom of a forest, presenting the POV of small animals such as frogs or dragon flies — perspectives that the human eye cannot offer.

In the Eyes of the Animal was commissioned by the festival Abandon Normal Devices. Festival commissions were a big funding source for them and most of these festivals were not film festivals. Because the work is cross-disciplinary, they were able to access institutions across many fields. These commissions were mostly funded by government funds. Partnerships have been key and sometimes Whitley was able to broker partnerships between festivals in order to pay for their projects.

With their project, A Colossal Wave, they forged an international collaboration with companies in Canada, which allowed them to access funds from another country.

Another part of their model of sustainability includes selling services. They make films, music videos, and other content for clients.

They also partner with universities to access funds earmarked for research. These funds provide them with the resources to experiment and innovate and the findings carry over to their other projects.

Whitley talked about their strategy of adapting their projects for many other platforms. She called them “vintage works” and “tourable assets.” Their installations are expensive to reproduce, so they figure out which parts can tour or be distributed online. License fees from the Oculus store is one source of funding.

A new model for the industry is a revenue-sharing model tested in the project, We Live in an Ocean of Air. In this case, Whitley’s team found an exhibitor, Saatchi Gallery in London, before it created the project and used the name of the prestigious venue to raise funds. The group also revenue-shared through ticket sales. This revenue sharing model is being watched closely in the industry.

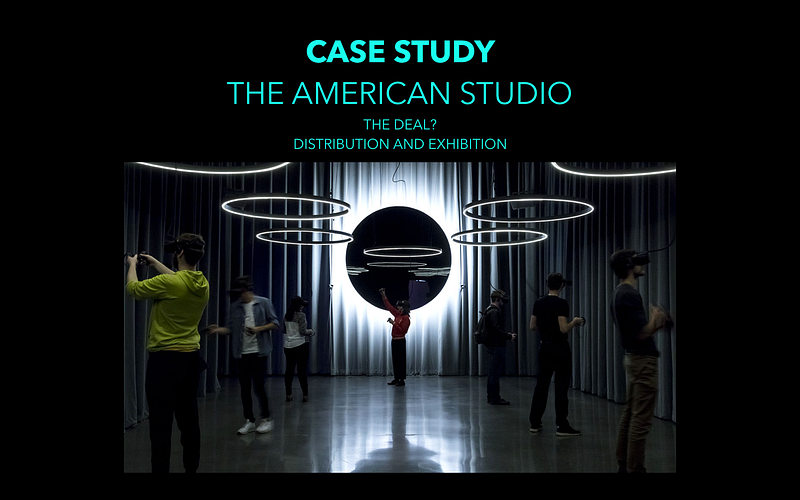

Case Study 3: The American Studio

The American scene is its own puzzle. Without substantial government funds and diminishing support from tech companies, it’s a struggle for creators to show investors that money can be made from XR products. But there is an emerging, albeit fragile, ecosystem with spaces for incubation and exhibition, funding from tech companies, and some distribution avenues. As of late, the XR ecosystem has been hit hard by the pandemic. The Tribeca Film Institute and Sundance New Frontier have both closed.

Incubators, fellowships, and artists services are a key support system. NEW INC is an important incubator in the field. Hundreds of people working in immersive media have gone through their program. They have a new initiative, ONX (funded in collaboration with Onassis USA), which will provide an accelerator program, work space and exhibition space — all holes in the existing infrastructure.

Organizations such as Mozilla, United Artists, Ford Foundation and MIT Open Documentary Lab‘s Co-Creation Studio all offer funded fellowships. A fellowship is an excellent model of sustainability because it supports the artist, not just a project. Artists services agencies such as Kaleidoscope offer a compelling model; they are trying to help artists every step of the way, from fundraising to distribution and exhibition.

Tech companies in search of content to sell their hardware have been a key funding source. VR headsets companies such as Oculus and Samsung drove the increase in content creation around 2016–17. That funding slowed down since VR headsets didn’t sell the way the companies hoped. But tech companies are still funding some content, including Ryot Studio, which is part of Verizon Media.

Scatter, an immersive media studio based in Brooklyn, is using the tool-building method to create revenue. Scatter’s tool is called DepthKit, a volumetric filmmaking kit, and Scatter is also creating the community around volumetric filmmaking.

Creators build the field—not only their projects—as they go along.

There was a notable distribution deal back in 2018 at Sundance when CityLights, a Los Angeles-based, VR financing and distribution studio bought the rights to Spheres for seven figures. Before the virus outbreak, people were looking towards public location-based exhibition spaces. But with the virus outbreak, people are still looking at public spaces for XR even more creatively while also more seriously considering web possibilities, headset improvements, and streaming.

It takes a village to show your piece and have impact. This is from the website of the project Tree by Winslow Porter and Milicia Zec. Tree has toured extensively, including at the World Economic Forum.

How will the field evolve?

- Wider VR headset adoption?

- More funders?

- More incubators, accelerators and fellowships, collectives?

- New spaces?

- Streaming experiences?

Time will tell.

Special thanks to the people who shared their knowledge and insights: Myriam Achard, Chris Barr, Mads Damsbo, Yasmin Elayat, Darren Emerson, Jess Engel, John Fitzgerald, Shari Frilot, Matthew Niederhauser, Rene Pinnell, Zahra Rasool, Alex Suber, Fred Volhuer, Eleanor Whitley.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.