Space-Making at Venice VR Expanded

An interview with Vincenzo Cavallo Faras (African Space Makers)

This year, Venice VR Expanded (September 2–12, 2020) was fully accessible online as well as at 15 “satellite” locations around the world. Preserving spontaneous encounters and engaging conversations, Venice’s experimentations in social VR brought “buzz” to its virtual programming. Festival-goers could access event spaces and live performances hosted in social VR worlds, as well as individual interactive works available for download on Viveport. Undoubtedly, the events faced challenges with making diverse interactive content foolproof cross-platform (particularly for Oculus Quest and Mac users), but the slippages and successes offered the broader XR community a deeper understanding of the inner operations and status of VR content today.

Upon logging into VRChat, I was greeted by Venice VR hosts who helped orient me to the Exhibition Hall and the VIP Garden. “Make sure to add us as friends,” one host said, “that way you could ‘Join Friend’ to get between rooms.” This was one of many pieces of advice shared after collectively learned experiences — expect the unexpected software update, beware of instancing issues on VRChat. Accessing the live performances, each requiring unique access codes, download links, and conversions between global time zones, made apparent the scale of the technological orchestra that was Venice VR Expanded. In many ways, following instructions, asking my way around, and learning the ropes to the social VR platform and how people interacted within it was as much a defining part of the experience as the selected projects.

My avatar (@andyk2020) at the

Venice VR Expanded festival in VRChat

My avatar (@andyk2020) at the

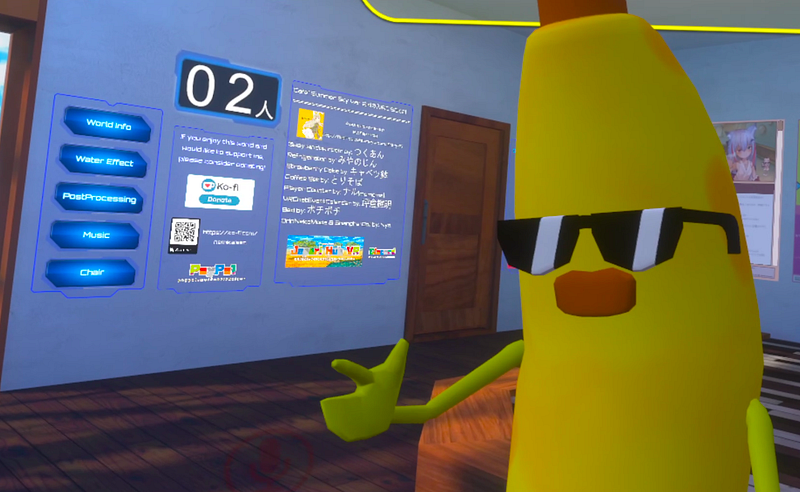

Venice VR Expanded festival in VRChat“VR is an ideal medium to explore space, which becomes the real protagonist of the story. The characters are more a link between you and the space to help you navigate it through their stories, their actions, their movement,” said Dr. Vincenzo Cavallo Faras, director of the 50-min interactive 360° VR work, African Space Makers. I met Dr. Faras, who was donned in a banana avatar, in the VIP Garden as we both were stumbling through our new virtual identities during one of the first days.

This spirit of experimentation is one familiar to Dr. Faras and Maasai Mbili, one of the featured collectives and a long-time collaborator of Dr. Faras’. African Space Makers takes participants through five art-making spaces in Nairobi, Kenya, in an Afro-punk choose-your-own-adventure style. Each story embodies an emerging frontier of urban renewal, much like the Nrb Bus Collective itself, a double decker bus revitalized into a creative studio where much of the scripting, workshops, and screenings of African Space Makers took place. “Urban storytelling is about space and space-making,” repeats our ‘trainer’ in the film, a mantra that centers the participants’ role as a co-producer of the narrative. The urban heroes who drive African Space Makers are more than just characters in the VR space of the film, they are our guides for reimagining the creative communities from which first-time VR makers emerge.

Below is the interview with Dr. Faras, which took place at a cafe in VRChat. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Still from African Space Makers

Behind the

Scenes

Still from African Space Makers

Behind the

ScenesAndrea: How did you get started with combining VR, as a space, with urban space-makers?

Dr. Faras: African Space Makers comes after two films that we have done about public space, public art, gentrification, and urban renewal. We have a Western idea of what a creative city should be and what it looks like — for instance, Amsterdam or San Francisco. But we want to show creative cities in African contexts and the collectives doing amazing things despite the fact there are limited funds or little effort from their governments to promote the creative industry.

Andrea: When you first shared the idea for your mission, were there any challenges? How did different art collectives respond?

Dr. Faras: Everybody knows the Bus. We are part of the scene. Everybody knows we are there and we will continue to be there, too. We are always doing workshops, and this is not a one-off thing. So it’s not like we brought people together — people were already together. What was more challenging, I think, was to manage the co-production between us, Black Rhino VR, and IN-VR in Berlin.

We did the pre-stitching and editing in Kenya, then sent it to Germany for the final part. It was a bit more challenging to coordinate different mentalities, different approaches to work, and different culture in order to create a new pipeline. It wasn’t easy, but it went well.

Andrea: For the people who were filming and acting, was it their first time using VR and 360 cameras? How did they adopt those skills?

Dr. Faras: For the actors and all the people involved as part of the production, they never did anything with VR. So at first they were really confused because many of them came from fiction [filmmaking]. They were used to close-ups and framing, but, in a way, it was more simple to shoot in VR. At the end, Kenyan creatives are very flexible and open people, especially Nairobi.

Andrea: When you were working with first-time VR users and creators, how did you describe the audience and what the VR industry looks like?

Dr. Faras: Ideally, my audience is young artists and decision-makers in urban policy making, but I tried to keep it spontaneous. When you go into this kind of process, if you think too much about the audience, you may end up thinking too much about what’s in the piece or what not to put in the piece. The only thing that mattered was what we were trying to say.

I don’t see why I should have to explain the VR industry to an actor. I just told them like, “Listen, guys, this is more like theatre. It’s not like film. It’s a one-shot thing, and the less we cut the better it is.” I taught myself VR, too, and the fact that I never did anything in VR, it’s good. So we’re just rock and roll.

It’s like when you are a child and you approach art and you can do what you want without caring about rules. You just do it. I have spent the last five years of my life trying to deconstruct everything I have learned in the normal cinema or documentary, because at a certain point people expect you to do a certain type of thing, with a certain type of language. You start to consume, produce, everybody goes to the same festival. And, on the contrary, because VR is kind of new, nobody really expects you to respect any rules.

Andrea: Did you find that you had to do a lot of the scripting? How did that process go?

Dr. Faras: Our participatory approach was straightforward. It was basically me spending a couple of days with each one of the collective, talking, sometimes smoking a joint and asking, “What are we going to do?” Period. Then I would go back. I would send them back the script. And the majority would be like, “This is hilarious.” We’re friends, so they would act like themselves and when we went to shoot, many things would change, too. So it’s not like the script has to be followed completely. And then we had the test screening in the headsets, so they gave us some feedback too.

Andea: In the scene with the street skaters, they ask the filmmakers, “you know, if we let you record us, what will you do for us in return?” Could you explain this dynamic between filmmaker and subjects?

Dr. Faras: That’s part of why I gave up on documentaries, because there is often exploitation going on. And it’s a dynamic that you cannot avoid because it’s embedded in the concept of Western documentary filmmaking. In the West, you can not pay the people who are into your documentary, because if you paid them, you are killing the realness of the film. But on the contrary, if you come and you live in Africa for a long time, you understand that you cannot ask someone to become the protagonist of your film without paying him or her or doing something in exchange. So Western filmmakers then find different ways either to avoid the responsibility or to find other ways to compensate. This is how it is. Now, in order to break that dynamic, you need to pay people and you need to have a proper contract that says, this is what I want to do and this is how much I’m going to pay you. In order to do that, I had to leave documentary filmmaking myself.

Also, I’m tired of portraying poverty. It’s not that it’s bad to make a documentary about poor people in order to highlight the situation. After many years of people doing that it hasn’t really changed the condition of people. It just makes the documentary filmmakers win awards. At the end of the day, I found that most documentary filmmakers are selfish people, with a few exceptions. With me, it’s a process. We are doing something together. You are useful to me, so I have to become useful to you. I cannot escape the responsibility. You know what I mean? Even if it’s just like, okay, I’m going to make a music video for you because you are an artist, in exchange for giving me your time for the interviews. Yeah. But some people don’t understand that.

VR Screening of African Space

Makers at the Nrb Bus Collective

VR Screening of African Space

Makers at the Nrb Bus CollectiveAndrea: In this film, you highlight the “space activators,” the filmmakers and the creative economy. Could you say a bit about the talent in this film?

Each one of them has its own story. In the story of Maasai Mbili and the Nrb Bus Collective they have been there for more than ten years and they are a point of reference for the community. It’s so important in a society to have these spaces where creativity is conducive and people can experience social interaction in a different way. For example, the story of the Jaba Juice collective is linked to how you can live in different spaces through a new framework — the idea that you can get high by drinking this natural juice in a way that doesn’t kill you. I think it’s just beautiful, the way they are all blending themselves with the music culture. Basically, these people all have different stories and they are role models for other people. You are in Nairobi and Nairobi is as cool as Berlin, if not more, because it’s more authentic in a way.

Interview with Dr. Faras in

VRChat

Interview with Dr. Faras in

VRChatAndrea: How has your experience been on this platform? Why did you choose your avatar?

Dr. Faras: I’m encountering a lot of problems because I’m on Oculus Quest, but I get the whole concept. I get the concept of meeting you in VR chat and having this interview. And it’s just amazing. Now, obviously there’s a lot of technical issues to solve, for example, how can we isolate ourselves without having to change positions when we are in a noisy place? Or how can we optimize for all types of headsets? It would have been nice if we could’ve accessed each piece, in the virtual word, without having to download Viveport. So, there’s a lot to be done. But honestly, these are technological issues that require some time. But, I think this festival has proven something that we never experienced before. It would be fantastic to create the same world that you see in African Space Makers in VRchat, so that you could actually be there. I mean, there is so much I want to learn. I don’t even know where to start.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.