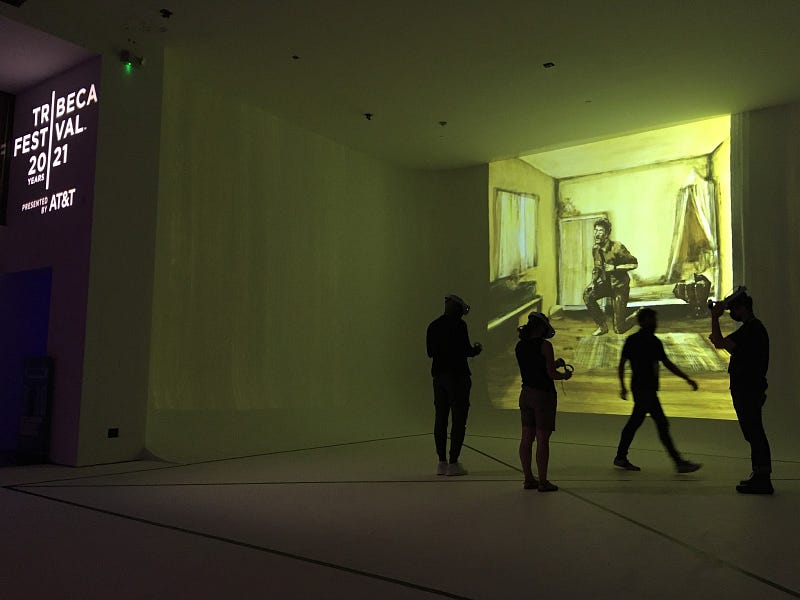

A dispatch from the 2021 Tribeca Immersive in-person exhibition

Four silhouetted figures stand in

front of a projection in a darkened room. Image source: Tribeca

Four silhouetted figures stand in

front of a projection in a darkened room. Image source: TribecaThis year, I attended the Immersive program at Tribeca Film Festival for the first time. Since I joined MIT’s Open Documentary Lab as a researcher last year, I’ve attended many online seminars that highlight the different ways mixed reality technologies can be used to tell stories. Thus, I came into the festival looking forward to experiencing first-hand the type of projects and technologies that I had previously mostly experienced through online platforms.

Storyscapes — Tribeca Immersive’s in-person exhibit at 50 Varick Street in Lower Manhattan — consisted of five projects from eight countries. From what I’ve heard, Storyscapes has been packed with VR enthusiasts in previous years. Yet this year didn’t feel so crowded; with tickets sold for a specific time and date, only four people at a time could experience the projects. As I waited for my time slot, I read Jupiter Invincible, an augmented reality comic book series about an enslaved African American, as it was on display as part of the festival’s Juneteenth programming. I then entered the venue, where I had the opportunity to immerse myself in a unique and colorful installation that primed me for the experience that would come as soon as I put on my headset.

My initial impression of Tribeca’s Storyscapes in person was very similar to what I had experienced online at virtual Sundance New Frontier in January 2021, both in terms of aesthetics and organization. Moving through the physical space of Storyscapes felt very similar to exploring the virtual space of New Frontier. One drawback of attending the festival physically was that, by design, I had to experience all the projects in a sequential order, which made the experience more standardized for attendees. In addition, I was worried that having to see all projects within a limited time window would increase the chances that I would develop motion sickness due to the continuous use of VR headsets. However, I was pleased that I completed the hour and a half exhibit without feeling dizzy at all. Although I believe that attending a festival in person has unique characteristics that are difficult to reproduce online, such as having the opportunity to be in a new place and meet other attendees in an organic social setting, as far as experiencing the projects themselves goes, I believe that both physical and online settings are similarly successful, especially as it pertains to mixed reality projects.

In this edition of Storyscapes, three projects — Critical Distance, Lovebirds of the Twin Towers, and Kusunda — explore the topic of eradication and the efforts to keep something alive. Within a custom-built screen projection cylinder, the only non-VR project at Storyscapes, Adam May and Chris Campkin’s Critical Distance takes us underwater into the audio soundscapes world of endangered orcas and their fragile ecosystem. Before starting, we were advised that the project was interactive and were encouraged to “touch” the whales to create a better experience. We put on the Microsoft Hololens 2 to commence. The experience uses augmented reality, projection, and holograms to portray a small group of 24 orcas — most notably, Kiki, a six-year-old female that lives off the coast of British Columbia. Sound was an important element for this experience. In the cylindrical structure, I figured out which direction to turn around to interact with new whales approaching me by locating where their sounds came from. Although the interactivity wasn’t as intuitive as I would’ve liked, I found myself smiling at how the whales illuminated when I “touched” them.

The five-minute piece Lovebirds of the Twin Towers by Ari Palitz and Tim Dillon is one of the shorter works at Storyscapes. In it, Carmen and Arturo Griffith, former elevator operators at the World Trade Center, reminisce about how they fell in love at work, surviving the building collapse during the 9/11 attacks and the anguish they felt over five days after the event, when they did not know if the other had survived. Audiences have no interaction within the VR experience, but the 3D models of the Twin Towers are well-detailed and brought us back in time to visit them. After completing the VR section of the project, audiences are invited to talk with Carmen. She was filmed answering questions about her life using StoryFile’s AI platform. Audiences were able to ask defined questions to prompt the pre-recorded answers. I wanted to interact with Carmen within the VR headset but didn’t have a chance; once the VR film was over, my group jumped to the next project, only allowing me to ask one question. Moreover, I would have appreciated being able to ask other questions apart from the prompts that were displayed.

Five storytellers sit around

a communal fire, listening intently. Image source: Nowhere Media

Five storytellers sit around

a communal fire, listening intently. Image source: Nowhere MediaKusunda — the winner of the Storyscapes Award — is a 23-minute experimental, speech-recognition VR docufiction about the Kusunda language. Created by Felix Gaedtke and Gayatri Parameswaran, this installation invites audiences to the mountains of Nepal. The project focuses on the language’s keepers, who are also co-creators of this project: 86-year-old shaman Lil Bahadur and his 15-year-old granddaughter Hema. During the making of this project, the original protagonist, Gyani Maia Sen, one of the final speakers of Kusunda, unfortunately passed away, necessitating significant changes to the story. Gaedtke and Parameswaran included a video interview from Gyani at the beginning of the experience to honor her. They use photogrammetry for the environments and volumetric video to capture their other protagonists. For Lil Bahadur’s recollections of his past in the jungle, they used Tilt Brush and animations. Audience members must speak certain words in Kusunda to choose their own narrative journey. What struck me the most were the different techniques Gaedtke and Parameswaran used to solve challenges, both during the production and delivery of the documentary. For me, Kusunda is strongest as an exploration of the different possibilities and affordances of VR.

An exhibit

staff member adjusts the headset of a participant for Inside Goliath.

An exhibit

staff member adjusts the headset of a participant for Inside Goliath.

The other two installations, Inside Goliath by Barry Gene Murphy and May Abdalla and We Are at Home by Michelle and Uri Kranot, are more gameplay-oriented. In Inside Goliath, a visual installation and 12-minute VR piece, voiceover narration from the main character Joe guides you through the sense of living with schizophrenia and psychosis. You embark on a visual journey through what feels like a neon arcade aesthetic with bright colors and a lot of movement. I felt disoriented, and at times the experience became overwhelming. There is one moment in which you can choose between listening to an expert explaining the symptoms of this mental health disorder or Joe’s feelings and thoughts. The meta component, which was the part that I enjoyed the most, is an arcade game within the VR project that narrates Joe’s recollections throughout his life, such as avoiding people, consuming drugs and alcohol. In sum, the project advocates for a participatory audience; it encourages us to move, think, and talk.

We Are At Home is a beautifully hand-painted, animated 45-minute multi-user VR piece that animates the themes of intimacy and voyeurism from Carl Sandburg’s poem, “The Hangman at Home.” The directors were awarded the Grand Jury Prize for Best Immersive Work at the 2020 Venice Film Festival for their single-user version of this project. Even though the audience spends most of the time as disembodied observers, this project allows for both the most movement and participation: you can open doors, windows, and cabinets. Each one of these actions are portals that reveal different tableaus, five in total, of intimate and private moments of other lives. To begin the experience, you need to light a match with the hand-held controllers. Even though the staff members explained to me how to light it, the action wasn’t intuitive for me; I felt puzzled. But after several attempts and the infinite patience of the staff, I successfully lit the match. In retrospect, understanding the mechanics of the project before starting was key to enjoying the rest of it. When the fourth wall is broken, and the characters look directly at you, I found myself wondering, should I be here? I had spent so long observing the characters that I felt caught by surprise and I looked to the other side just to realize that I was in a “closed-room” without escape. The project explores different forms of engagement in which different scenes require audiences to play different roles. For example, there is a room in which I could interact with different objects — such as stir a tea bag or play a piano — that were excerpted from the previous scenes. This felt special because it was the point when I transitioned from being a passive observer to an active participant. The climax of the experience is when you are left with the task to burn a pile of books. You have no idea who is coming, but I, at least, felt the responsibility to burn those books. I immediately regretted it because the space around me started “burning”! As we stepped out of the Storyscapes building, I went back to my reality and wondered what I would have done had I been left with the responsibility of burning the books in real life.

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and Dot Connector Studio, and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. The Gotham Film & Media Institute is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.