Observations from Festival du Nouveau Cinéma

Recently, I’ve been thinking about how one’s understanding of VR greatly depends on one’s first encounter with the medium.

My first experiences with VR were all at film festivals — specifically, Festival du Nouveau Cinéma (FNC) in Montreal. For the past few years, FNC has curated a series of VR works in its eXPlore section (including cinematic, interactive, location-based, etc.) with a focus on making these new media experiences accessible to the general public. Considering VR devices are only just now making their way into households, it’s interesting to see how FNC chooses to present VR to people who wouldn’t have a chance to see it otherwise. Because FNC remains primarily a film festival, I’ve also been curious to see whether and how FNC eXPlore opens up to experiences that challenge the moniker of “cinema.”

FNC

eXPlore’s “Cinéma VR” selection is hosted inside Complexe Desjardins, in the heart of Montreal’s

Quartier des Spectacles.

FNC

eXPlore’s “Cinéma VR” selection is hosted inside Complexe Desjardins, in the heart of Montreal’s

Quartier des Spectacles.Accessibility

To make VR accessible to the general public, FNC hosts its VR selection in the middle of a mall, next to the food court, completely free of cost. A sponsorship from Samsung outfits the festival with a collection of smartphone-powered “Gear VR” headsets, which, although not as powerful as the Rifts and Vives of the world, are plenty to showcase the majority of works each year that fall under the category of “cinematic VR” (360° videos in all but name).

“VR films”

at FNC are presented free of cost on Samsung Gear VR and Oculus Go headsets

“VR films”

at FNC are presented free of cost on Samsung Gear VR and Oculus Go headsetsIn past years, each head-mounted display was dedicated to a single film, which meant a lot of waiting in line. For the 2019 edition, all cinematic VR works were loaded on to every headset to cut wait times and ensure anyone passing by on their lunch break or doing errands had equal opportunity to see the films.

One project in this space was shown on separate Oculus Go headsets, 21–22 Alpha by Thierry Loa. The first in an ongoing series of VR films, 21–22 Alpha deals with the Anthropocene by contrasting images from pristine landscapes with shots of major urban developments that confront the viewer with humankind’s profound impact on the planet. Using a series of drone shots and no narration (save for a few opening and closing words) Loa’s film stands out from the VR selections of years past by using VR’s ability to foster a sense of presence for reasons other than putting the viewer in the body of a character in a narrative.

Based on what I’ve seen at FNC eXPlore, cinematic VR seems to have moved on from the gimmicks of years past and beyond the conventions inherited from narrative cinema in favour of more subtle strategies for immersing viewers in spaces that would otherwise be inaccessible to them. The Rain That is Falling Now Was Also Falling Back Then, by Christian Zipfel, falls in a similar category by documenting the lives of three men in Botoșani prison, Romania. Zipfel, who brought us Rooms last year, continues his project of showcasing spaces typically hidden behind closed doors and the rituals that govern them. The Rain offers a glimpse into the daily routines of the three men trying to make life bearable inside the prison, considering the challenges they’ll face once they leave.

One last VR film is worth mentioning, as it won the “Prix Cinema VR.” Last Whispers: an Immersive Oratorio by Lena Herzog is presented as an invocation of languages that are either extinct or on the verge of disappearing. The film focuses on audio from these languages with sober visuals — a black-and-white representation of the globe seen from within — that back up the spoken words. For the majority of the experience, the Earth rotates around the viewer and points light up on the map with the name for the corresponding languages. I must agree with Alex Ross, a critic for The New Yorker, who fittingly described Last Whispers as “a very haunting and singular experience.”

“Immersive VR”

More works still were tucked away in another venue (a nearby university campus) and assembled under the banner of “immersive VR” (confusing as that name may be).

Put simply, these were interactive pieces that ran the gamut from small games and interactive narratives to a variety of takes on the documentary format. The two most notable titles, in my experience, were Another Dream by Tamara Shogaolu and Common Ground by Darren Emerson. The former uses animation to tell the story of an Egyptian lesbian couple who fled Cairo to escape oppression. Here, once more, VR serves to supplement what the two subjects of the piece are telling us about their experience; the animated spaces illustrate and clarify what they describe without diminishing the power of their words. Although limited in terms of interactivity, Another Dream has viewers trace the Arabic words for each chapter of the documentary, an ingenious strategy to draw viewers deeper into the story.

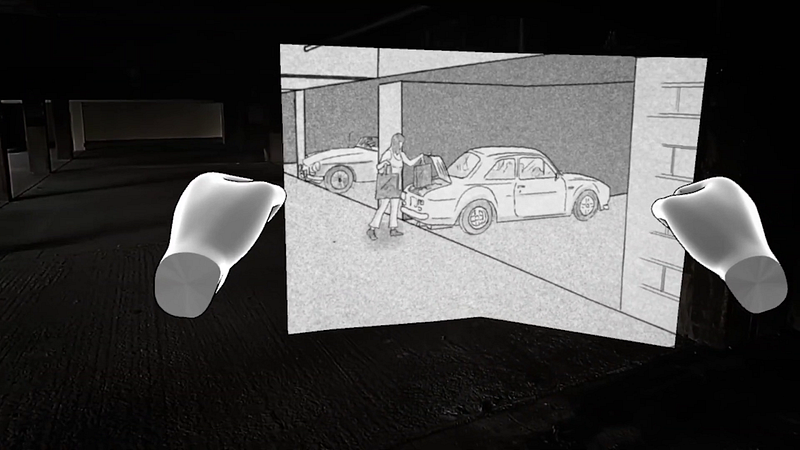

Still from Common

Ground showing the pamphlet that reveals the once-imagined future of Aylesbury

Estate.

Still from Common

Ground showing the pamphlet that reveals the once-imagined future of Aylesbury

Estate.Common Ground focuses on the Aylesbury Estate, at one point the biggest social housing project in Europe, as it is being demolished. The documentary follows homeowners who shine a light on the troubled history of social housing in England as they continue fighting against the council trying to displace them. As we move through the different spaces of the estate, talking head segments and archival images are projected on the sides of buildings and, at other times, viewers are given tools to peer into Aylesbury’s once-imagined future or to learn about news coverage by flipping through a virtual newspaper.

Both of these VR documentaries continue a trend I noticed in the VR “films” at FNC this year: namely, that of moving away from tools inherited from cinema (e.g.first-person points of view) and towards more nuanced encounters with space and the subjects that inhabit them. Considering Common Ground won the “Grand Prix Innovation” for best interactive or VR project and that Another Dream’s Tamara Shogaolu won the “Best XR Pitch Award” for her upcoming project They Call Me Asylum Seeker, things are looking bright for the continued development of VR as a medium with its own language distinct from films or games.

Felix & Paul Master Class: “Unlearning Cinematic Conventions”

In addition to the VR works at FNC eXPlore, the central event was a master class from local VR studio Felix & Paul, makers of such experiences as Miyubi, The People’s House, and Travelling while Black.

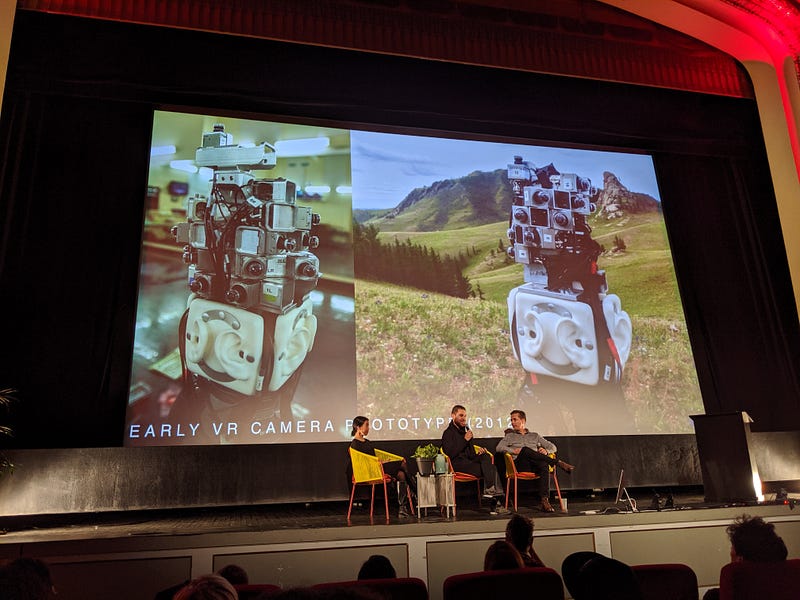

The presentation featured the studio’s eponymous co-creators and creative directors Félix Lajeunesse and Paul Raphaël. The two took turns explaining their goal of reproducing what they felt was most immersive in cinema — namely, its ability to create an “experiential” feel. As the title “Unlearning Cinematic Conventions” implies, the two creators were wary of simply reproducing strategies inherited from cinema and instead focused on their early attempts with stereoscopic 3D and expanded cinema installations, which eventually led to experimenting with VR. Speaking from years of experience, Lajeunesse and Raphaël told us about their vision for cinematic VR, which spoke to the inclinations of this film festival audience.

Félix

Lajeunesse and Paul Raphaël during their Master Class. Felix & Paul is a Montreal-based VR

studio.

Félix

Lajeunesse and Paul Raphaël during their Master Class. Felix & Paul is a Montreal-based VR

studio.After the master class, I asked Lajeunesse about the problem of accessibility still faced by most VR works. He confirmed that VR projects will get most of their exposure from festivals such as FNC, but added that ensuring continued engagement requires additional efforts, such as touring a location-based version of the project. Ultimately, Lajeunesse described the need to move beyond the current platforms and hardware-dependent ecosystems to the more ubiquitous context of “spatial computing.”

While Lajeunesse looks forward to this post-screen world where “all the content will move towards immersion,” where “content will be deployed to a platform that is immersive and interactive,” I can’t help but wonder about how this will influence the types of works being created. As expansive a platform for XR as this future might have for us, it will entail a new learning period and the creation of experiences that depart from the “cinematic VR” of today, which remains a product of the head-mounted displays that make it possible.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.