Field Notes: Why It’s Time for “Retrocycling”

How one artist carved a path through obsolete technologies

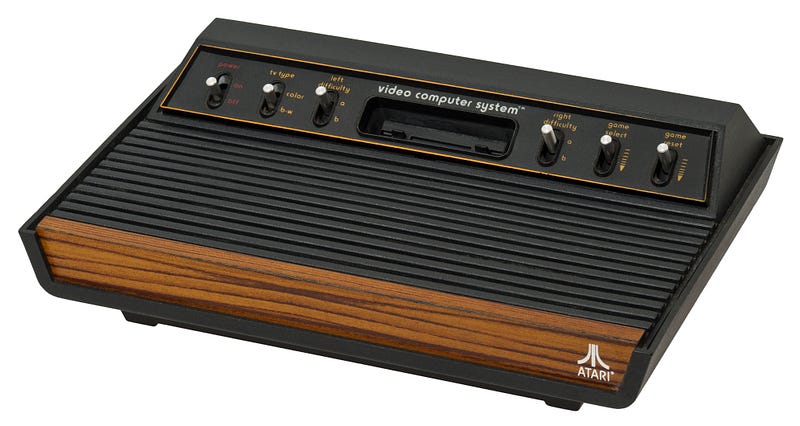

Over the past decades, I have explored different approaches for repurposing outdated technologies, including video game consoles from the 1970s; TVs and slide projectors from the 1980s; CD players, computer supplies, and VR equipment from the 1990s; and so forth. One example of a now-obsolete device that has been part of my artistic practice since the mid-1980s is the Atari 2600. Such devices also hold promise for the makers of nonfiction narratives and experiences who read Immerse.

Many of these discarded devices were designed and engineered to last longer than we expect from today’s appliances. They were expensive as well. But as we move further and faster towards the development of new technologies, we are starting to forget about these machines and their capabilities.

I’d suggest that it is time to “re-plan” obsolescence and start thinking about what we can do with the countless consumer electronics produced until now. Historic technologies have the power to calibrate our actions and spark the curiosity of young generations about new uses of old hardware. Framing those technologies as artistic endeavors not only could help to maximize their potential, but also increase their use and value. It is time for what I call “Retrocycling.”

Atari 2600

Video Computer System, 1977

Atari 2600

Video Computer System, 1977We associate Atari with classic video games: Pong, Pac-Man, Space Invaders, Asteroids, Adventure, etc. Yet, it is not well known that Atari’s founders made the first commercially available, coin-operated video game, named “Computer Space,” and manufactured the first arcade, which featured an “Easter Egg” (a hidden secret or item) called “Starship 1.”

Atari also introduced the first widely used cross-platform game controller, conceived some of the initial VR technology, and patented the first electronic music visualizer. Besides AT&T and Xerox, Atari was one of the few key companies that reshaped our notion of technology. In 1982 the corporation became the fastest-growing company in U.S. history. Brilliant engineers, programmers, designers, and visionaries, including Steve Wozniak, Steve Jobs, Thomas G. Zimmerman, and Jaron Lanier, worked for Atari.

Atari

Mindlink, 1984

Atari

Mindlink, 1984By 1984, Caracas (the city where I was born) was flourishing with arcade places. I would spend hours — as well as my allowance — just playing and trying every available title. That year, I got an Atari 2600 as a birthday present. I couldn’t contain my excitement for days!

Having a gaming console at my disposal offered me the opportunity to experiment. Eventually, I found a way to transform the video game system into a computer. I tasked myself with programming a series of colorful real-time videos, showing the transition from code to natural language, visuals, and sound. As a result, the Atari console became capable of generating random-based interactions between two rectangular characters, displaying binary messages, 8-bit compositions, and philosophical questions.

Atari Ex

Machina, 2007

Atari Ex

Machina, 2007These projects, which resembled automata, made me wonder about the human potential of technology. How can both natural and programming language be employed to humanize machines? Is it possible for a computational device to provoke an emotional response?

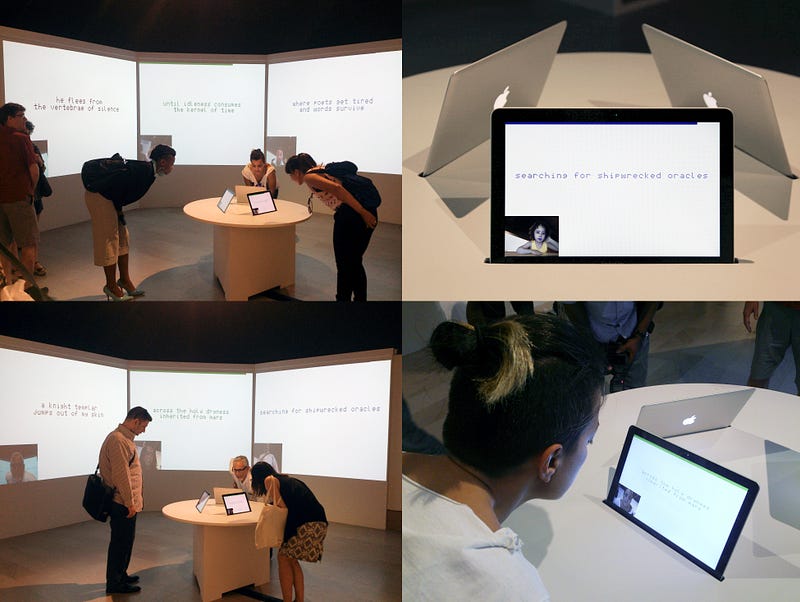

Since poetry is the literary form in which language has a special intensity given to the expression of feelings, it seemed reasonable to place poetic texts on the screens and allow others to experience new poems by enabling the machine — and its users — to recombine verses that I previously wrote. Poetry was my answer to bring machines to life and narrow the distance between people and technology.

Facial

Poetry, 2014

Facial

Poetry, 2014In the 1990s, I made several works that explored this premise, such as the Poetic Clock (1997), an electronic clock that transformed time into poetry, generating 86.400 different poems every day. The content, placed on a now-vintage computer, was transmitted to an LED board comprised of 4 rows. Every time an hour changed, a new verse was displayed on the first (top) row. Sentences representing the passing of minutes were printed on the following line. When a second changed, a new sentence popped in the third row. Finally, the fourth (bottom) row, had the time showing as HH:MM:SS.

The reading of the three verses on the Poetic Clock gave rise to an articulated and coherent poem, a poem that was constantly changing, becoming another of itself, and displaying through language the movement of time.

The Poetic

Clock, 1997

The Poetic

Clock, 1997Watching the indefinite continued progress of hours, minutes, and seconds become a poem, added another dimension to the act of reading. The Poetic Clock was dispensing not only poems but also a poetic experience, an experience that could be stunning for some and irritating for others.

Given that seconds change at a fast pace, by the time people tried to read the third sentence, the sentence was already gone. Also, depending on the participant, the natural rhythm of time placed a challenge that turned the experience either into a speed-reading exercise or a memory game. Filling the missing words evoked different responses. The fact that the machine was performing a poem rather than just delivering text prompted an emotional response in the observer.

Time and performance have been reappearing as themes in my other works, including Super Atari Poetry (2005), a multiplayer game installation consisting of 3 Atari 2600 consoles, joysticks, self-manufactured cartridges, and old TVs. Each Atari held a game cartridge with a group of verses that could be reshuffled using a joystick. It enabled up to three individuals of any age to participate, have a meaningful social interaction, and co-create hundreds of different poems together.

Super Atari

Poetry, 2005

Super Atari

Poetry, 2005Like the Poetic Clock, Super Atari Poetry challenged the conventional way of reading. Besides the non-linear format and interactive features, operating a video game console from the 1970s to convey poems on 1980s televisions added a time-traveling feeling.

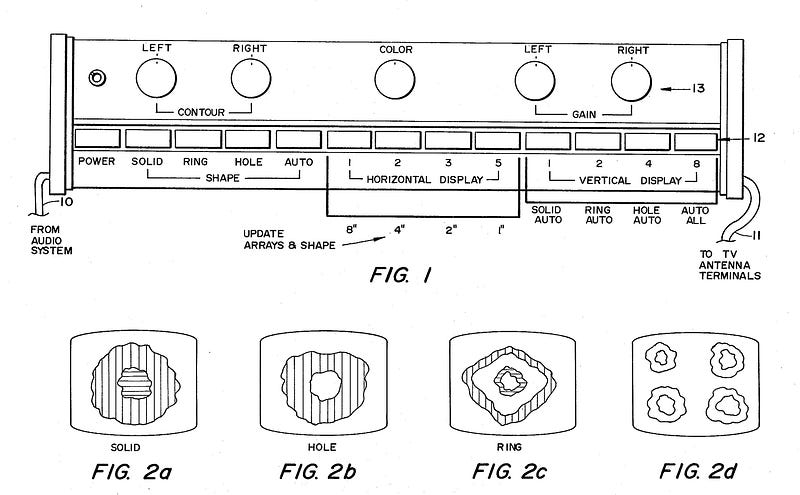

Acknowledging the existence of obsolete technologies that guided social and technological transformation was one of the main reasons behind these works. It also provided the impetus to create C-240 (2001–2014), an electronic sound installation developed to investigate the contemporary significance of the music visualizer as a social vehicle.

Atari Music

Visualizer, 1976

Atari Music

Visualizer, 1976The installation used the first electronic music visualizer, invented by Atari in 1976, and described as an “audio-activated video display.” Via sensitive transducers, C-240 was able to translate sounds from the urban environment into flamboyant geometric patterns. The generated shapes evoked Pre-Columbian textiles and early computer graphics.

In 2014 the work was installed and connected to FIESP’s 40,000 ft square LED building façade, located in the heart of São Paulo, enabling passersby to speak into a microphone and watch their utterances become real-time visuals on the building’s gigantic electronic façade. The different levels of communication, interaction, and feedback that I received assured me of the potential of outdated technologies in today’s global landscape.

C-240,

2001–2014

C-240,

2001–2014Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.