User experiences of immersive media at IDFA’s DocLab

Stories are a constant in the history of media. They have been told, recorded, and transmitted in image, sound, word, and data. And yet most of our ideas about story — about narrative — derive from media with a particular set of attributes. Narrative theory has emerged primarily from studies of literature and cinema, forms associated with the media of print and film. Both share characteristics of stability (fixed word and frame sequence), attribution (there is an author somewhere), and one-to-many distribution (identical copies reach a multitude) — all perfect conditions for story-telling as we usually define it.

A

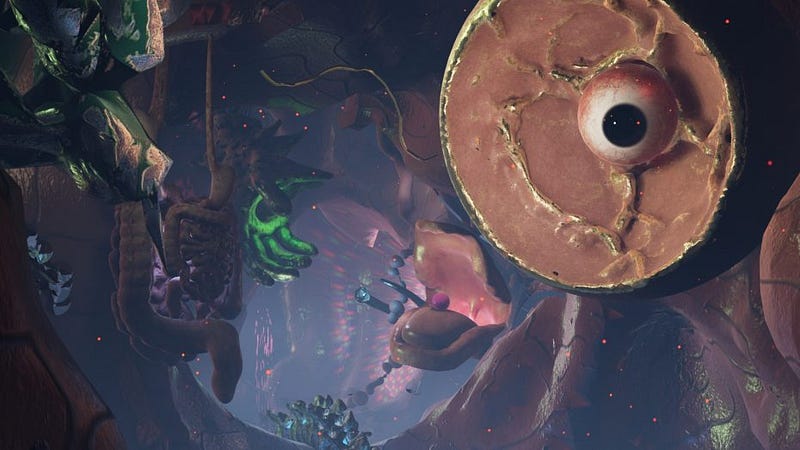

Symphony of Noise VR, one of nine IDFA projects included in this study.

A

Symphony of Noise VR, one of nine IDFA projects included in this study.But what about stories that inhabit “unstable” media forms, or that are collectively created, or that exist as unique instances? Are they lesser-narratives or even non-narratives? Are stories limited to particular media — or do they pervade human experience and with them a wide array of expressive systems, interactive media included?

This article summarizes the findings of a research project that considers narrative experiences in immersive settings, where users can interact with structured worlds. While the project focuses on user experiences in various immersive forms (including 360 and real-time capture Virtual Reality, locative audio, and an AI story generator) its findings are more broadly relevant to other forms such as augmented reality, alternate reality, and video games, and interactive documentaries. These cultural forms allow users to find their own way through a constructed environment; they exist as collaborations between the user and environment-designer; and in most cases, they yield unique experiences. Their affordances couldn’t be more different from those of print and film, which are used to “tell” stories; rather than writing them off, can these experiences instead be described as enabling users to “find” stories?

The question matters because it has implications for how we use immersive and interactive media. We can of course retrofit them to behave like film, just as the film medium’s pioneers retrofit their medium to behave like theater. And while such a move could be an aesthetic or even economic choice, it is useful to understand the alternatives, that is, the fuller array of possibilities that media make possible.

Bodyless,

Hsin-Chien Huang (2019)

Bodyless,

Hsin-Chien Huang (2019)We, researchers from MIT’s Open Documentary Lab aided by researchers from Utrecht University’s Department of Media and Culture, carried out this work with audiences at the 2019 International Documentary Festival Amsterdam’s DocLab exhibition, which showcases immersive experiences. The research was carried out in the context of IDFA’s Immersive Network Research and Development Program. We gathered and analyzed several hundred audience responses to nine immersive productions — A Symphony of Noise VR; Bodyless; Common Ground; Lagos at Large; Nerd_Funk; Only Expansion; Reflector; Rozsypne; and The Waiting Room VR.

The research considered the intersection of narrative psychology and immersive media forms such as virtual reality (VR). It’s fair to ask what one has to do with the other, but the connection is not completely strange. For example, VR has been prominently inscribed within the psychological domain of affect theory, and widely championed as an “empathy machine” and “intimacy engine.” There are good reasons to challenge this view, not because of affect theory but because of the mechanistic assumptions about media’s relationship to its users, which harken back to the old days of media effects. By contrast, the use of narrative psychology with immersive media does not assume mechanistic effects, but rather provides a diagnostic instrument for understanding users’ meaning-making strategies — and the varieties of their narrative encounters.

“Meaning-making strategies” and “narrative encounters” cover a lot of ground. In researching this project, we wanted to find out how immersive media users organized their experiences. Were their encounters coherent or incoherent? If coherent, what forms did they take — story form? and if so, what was the nature of the story? Other forms? How did users describe them? We also wanted to find out whether and how user-experiences and maker-intentions mapped onto one another: Were the stories that makers told the same stories that users experienced? Which did users find more engaging: the stories “told” by the maker or those that they “found” themselves? And could we perceive any patterns that distinguished users who preferred to be “told” a story from those who preferred to “find” their own, for example, users accustomed to fixed media versus those more accustomed to interactive media?

Before turning to our findings, it is worth situating this project in the wider field of narrative studies.

Notions of narrativity are expanding from a concern with textual structures that characterizes literary and film theory, to include a wide range of human experiences. Consider the narrativist strand of historiography, where people such as Hayden White consider the narrative construction of reality; or narrative psychology, with Dan McAdams’ focus on narrative and coherence and Jerome Bruner’s on narrative as a way to contain life experience; or the work of philosopher Paul Ricoeur on narrative as a way to harness the “discordant” in life. (Beyond Narrative Coherence provides an excellent overview.) All attest to the wide-ranging uses of narrative as strategies and frameworks outside of the literary theoretical context. And all offer possible ways to think about how users make sense of their experiences in immersive and interactive media.

Our approach was inspired by Jerome Bruner’s work, particularly his technique of asking subjects to “write a story” that the analyst could use as a way to discover the subject’s world. Factors such as person (“I” or “you” or “he/she”), agency, and voice were as important to Bruner’s analysis as the world depicted and the manner of its depiction. Did the subject “witness” a scene, or were they involved as an element of or an actant in the scene? We adopted this close-reading approach in order to understand how users experienced particular immersive projects. Our questionnaire asked users to describe what happened after they put on the VR headset, it asked for basic demographic information, and it sought to ascertain both the user’s level of familiarity with these forms and their genre preferences. The survey was carried out in English and Dutch since IDFA is an international festival in the Netherlands, and we gave participants a choice of writing or speaking their answers.

Lagos At

Large by Jumoke Sanwo (2019)

Lagos At

Large by Jumoke Sanwo (2019)The larger research process included assessing the literature on non-fixed story forms and narrative experiences; interviewing makers with backgrounds in both linear and non-linear media about their notions of stories, story worlds, and design implications; and assessing the immersive and interactive installations at IDFA in terms of their narrative framing strategies (such as descriptions, reviews, and thematic physical settings).

Since this is the first deployment of the research method, we intend to learn from the results and refine them for subsequent use. For example, the spoken interviews yielded much richer information about the users’ experience than did the written questionnaires, but what did this reflect? Self-selection? (Did users willing to invest more time speak and users with less time complete the questionnaire)? Or did interaction with the interviewer play a role? (All members of the research team were equipped with printed questionnaires as well as audio recorders and interview protocols). Or were non-native English and non-native Dutch speakers more comfortable speaking than writing? Or was there a performative dimension involved (questionnaire completion is private; recorded interviews were in some cases semi-public)? Concerns like these require more investigation as we refine our process.

For these reasons, the study’s findings are necessarily preliminary. But preliminary or not, they are also clear in their implications for how we conceive of immersive media, and with them, the relationship between the maker and participant. Existing models for this relationship range from directors and audiences familiar from film, to collaborative scenarios in which story-world designers and participants work together to create narrative experiences.

If immersive media are to develop from awkward storytelling systems and realize their potential, it will require a much better understanding of an expanded repertoire of strategies for narrative engagement — the goal of this ongoing research initiative. Narrative, of course, is not the only path for these media to follow; but if other time-based media are anything to go by, narrative will play an oversized role in their popular manifestations.

Methodology

We gathered and analyzed reactions to nine immersive projects: A Symphony of Noise VR (Michaela Pnacekova); Bodyless (Hsin-Chien Huang); Common Ground (Darren Emerson); Lagos at Large (Jumoke Sanwo); Nerd_Funk (Ali Eslami, Mamali Shafahi); Only Expansion (Duncan Speakman); Reflector (Piotr Winiewicz, Dawid Górny); Rozsypne (Nienke Huitenga-Broeren, Lisa Weeda); and The Waiting Room VR (Victoria Mappelbeck). Most of the projects fit under the broad rubric of Virtual Reality (VR), with two exceptions: Only Expansion, an immersive audio walk, and Reflector, an artificial intelligence system that edits video in real-time based on audience-selected parameters (shot length, color, framing).

Our method was straightforward: when people completed their experience, we asked them to fill in a short questionnaire or, if they preferred, answer a few questions verbally. We gathered basic demographic information; the level of familiarity with VR; and any obvious genre preferences. We also asked participants to describe their experience as if relating it to a friend — what happened? Each of the nine projects had between 35 and 55 respondents, with a total of 310 written and 68 spoken responses. Nearly 40% of the respondents indicated that their experiences at IDFA were their first contact with the VR medium. Another 30% described themselves as very familiar with the medium and its different systems. Gender-identity skewed female (65%) and participants were fairly well distributed across the age spectrum.

Several broad correlations emerged on the periphery of our work that seem worthy of further investigation, even if they conformed to stereotypes.

Participants who identified themselves as new to VR tended to be the most effusive about the sense of presence and frequently referred to themselves in action mode (“I flew’, “I discovered’, “I felt like I was in the shoes of the characters’). Participants who reported being quite familiar with VR tended to describe the projects’ effect in the second and third person but rarely first.

Certain projects (Bodyless, for example) produced a cluster of comments regarding feelings of nausea and dizziness. In our relatively small sample for this project (fifty respondents), 100% of these comments came from subjects identified as female (seventeen of thirty-one). Gendered reports of this kind for projects outside our sample are persistent and merit investigation.

Male viewers, particularly those who identified as experienced in the sector, tended to be the most critical of projects. Rather than describing their experience as prompted, they often evaluated the strengths and weaknesses of projects and techniques, drawing comparisons to other projects. Their mode of address tended to be evaluative rather than experiential.

Nerd_Funk,

Ali Eslami, Mamali Shafahi (2019)

Nerd_Funk,

Ali Eslami, Mamali Shafahi (2019)Story or no story?

The VR projects deployed a range of organizational strategies: inviting participants to improvise (A Symphony of Noise VR, Nerd_Funk), to reflect (The Waiting Room VR, Bodyless), and to engage in a more-or-less linear trajectory (Common Ground, Lagos at Large, Rozsypne).

A Symphony of Noise VR, the most abstract of the projects, elicited descriptions of the process and evaluations of the experience (“fun,” “like playing a really beautiful video game”). None of the respondents described their encounter in narrative terms. Nerd_Funk, improvisational but also more tangible, elicited what might be termed narrative frames: “an XTC trip, all by myself, intense, distracted by the telephone, alone, loved it”; and “digital LSD, immersive, grotesque … the way we’re going to party in 20 years”. Nerd_Funk’s imagistic vocabulary resonated in particular with younger users, one of whom described it in dream-terms: “I think I was holding a phone and liked the part where the phone gives a notification. (I was trying to take a selfie with the phone. Curious about how I look!)”

The Waiting Room VR was embraced — or rejected — as an experience. Female-identified participants — and those who mentioned having friends with cancer — generally embraced it as emotionally moving. These descriptions were empathetic rather than sympathetic, sometimes in the first person, with participants identifying through the VR character or through their friends. Those who rejected the experience as “boring” and “static” generally described the situation (“a woman is getting chemotherapy,” “someone is dying”), and dismissed it. Common to both sets of responses was an acceptance of the project as an experience (of chemotherapy, of coming to terms) and not as story. Bodyless, by contrast, elicited comments about its mechanic — flying, floating — and often about the narrative world (“the story of my journey after death,” “in a twilight world between memory and fantasy in Taiwanese history,” “a visit to the gateway of hell”). Interpretive latitude was extensive, and Bodyless offers a good example of how the framing of a project through information and reviews can structure an experience, or be ignored, opening up quite divergent readings.

Nearly all of the reactions to Rozsypne agreed on basic elements (“sunflowers,” “falling bodies,” “an old lady”). However, users experienced them as either witnesses or participants. Using the “I” or “you” form, participants described textures and at times expressed a reluctance to explore the emotionally charged events. While the story was well-known from the news, the project’s intimacy and the freedom it gave users to look or not evoked emotional responses.

The

Waiting Room VR, Victoria Mapplebeck (2019)

The

Waiting Room VR, Victoria Mapplebeck (2019)Common Ground likewise elicited strong responses, giving users access to the intimate side of gentrification. As with Rozsypne, users came to the project with a relatively clear understanding of the underlying events, giving greater latitude to their exploration of the world. Beyond repeating the project’s informative text, users commented on their closeness (sometimes bordering on transgressive) with the Estate’s inhabitants.

Lagos at Large was “like visiting Lagos with a friend,” said one user. Many commented on the feeling of “being there,” a feeling complicated by the soundtrack, which evoked quite different responses. Much like Nerd_Funk, many users inscribed their experience of Lagos in narrative frames (“I wandered the streets,” “a tourist information movie”); but virtually none discussed their encounter with the world in narrative terms. Only Expansion, an immersive sound project that mixed recorded with amplified live sounds, was described in much the same way. The narrative frame drew attention, and the sound mix was assessed; but discussion of the experience itself, as well as any sense of story, were generally absent.

Across the projects, the clearest correlations appeared between relatively inexperienced users and both the use of person (beginners say “I” more frequently than others) and the physicality of effect (“I flew,” “you rode around Lagos”). For our investigation of narrative, variation among narrative frames (what position does the user embody?) was pronounced, even in those examples where the intertextual frame was clearly defined (gentrification in Common Ground and the downing of flight MH17 in Rozsypne). Interestingly, users of both relatively abstract productions (Nerd_Funk) and narratively-structured (Rozsypne) spoke in equal measure about their narrative frames. This “framing” is a key variable, both shaping and revealing how users approach an experience. And it seems to be a variable that can be controlled through the staging of a project more than through pre-existing knowledge. Although Reflector fit poorly into this immersive group, it offered a great example of the power of framing: those who read about the experience first seemed to enjoy exploring it, and those who didn’t seemed lost. The project represents an important step in personalized story generation, and we are exploring it in the context of an ongoing AI project.

Our research instrument needs considerable improvement. Too often, questionnaire respondents “reviewed” projects rather than sharing their narrative experience. Audio interviews produced richer data, and for the next round, we will focus more on individual and group interviews. We have gathered a number of tantalizing correlations in the responses regarding perspective and tense as indicators of agency, and are eager to test them with both real-time capture VR and 360 video. And we will drill down on the notion of narrative framing as a determinant in “story finding” for the project’s next iteration, trying to better understand its role.

Rozsypne,

Nienke Huitenga-Broeren, Lisa Weeda (2019)

Rozsypne,

Nienke Huitenga-Broeren, Lisa Weeda (2019)Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.