When you have six days to put a documentary festival online

T-Minus Six

It is late on 11 March and all the installations have been delivered so that we can start building the CPH:DOX interactive showcase in Charlottenborg, the art gallery in Copenhagen that is also the festival HQ. As curator of the Interactive Exhibition, I was due to travel there from London to oversee the install. This is the moment when it usually starts to feel real – but now, less than a week before the festival’s planned opening, the decision is being made to cancel the physical event and to put as much as possible online.

In the days and hours leading up to this, the core administrative team has been under a huge amount of pressure. They have scores of legal requirements and contracts to fulfil and not to do so would be to jeopardise the very future of the festival. But they also feel an overwhelming responsibility to protect the local community, as well as festival delegates, by not creating an event where Covid-19 could spread. There is no consensus on what to do between the state, the city, and other cultural institutions. The government’s position is that it is up to each organisation to set their own policy, within existing public health guidelines.

Without a clear directive from the government, they find themselves damned if they cancel the festival and damned if they don’t. Inevitably, the moral responsibility weighs more heavily than financial considerations and they start preparing themselves to cancel the event and face a financial catastrophe that could spell the end of CPH:DOX.

The core team (Tine Fischer, the Festival Director; Katrine Kiilgaard, the Deputy Director; the film programmers and the press officers) gathers together in the evening to watch what will be for them a key speech from the Danish Prime Minister. Will there be a clear government directive that they can follow? Or will they be left to decide to cancel the festival by themselves?

Photo:

Niklas Engstrøm

Photo:

Niklas EngstrømThankfully, in this speech, the Prime Minister decisively shuts the country down, announcing the closure of the borders and bringing to an end their lonely period of existential agony. They have already made the mental leap to cancel the physical festival, but this makes implementing the decision a hell of a lot easier. However, they can’t bring themselves to leave it at that. As Katrine puts it, “Everything was printed, posters were hanging around the city. It was impossible to postpone and we were resistant to letting all this go down the drain.” The only alternative is to go online.

Kenneth Sorento, the first-time director of the opening film, The Fight for Greenland (about the evolving cultural identity of a new generation of Greenlanders), is a cinematographer who never went to film school. This was going to be his big premiere.

“All these people who prepared and got selected – it was not possible to let them down. There was no way you could not try to find a solution,” said Katrine. The team also realises that most of the Spring and Summer festivals around the world would likely cancel, so they feel a strong responsibility that they have to make this happen. The DOX team springs into action right away.

Niklas Engstrøm, Head of the Programme Department, starts ringing stakeholders and the first reactions are so encouraging that they just go for it. It is clear from the outset that the industry will support DOX in finding a way to maintain the momentum to continue this event.

He starts with the industry trade journals, who confirm they will cover an online festival. Then the juries all agree to conduct the competition online. Then the sales agents and distributors say they will watch the films streamed. Now this means they have something constructive to offer the producers – that including their film in the festival will be beneficial for them.

“At first we made an agreement with the streaming platform that we would have only 40 titles – that was the maximum capacity they thought they could implement in such a short time, and to be honest, at first we thought it was an ambitious goal – to convince 40 filmmakers to present their films, many of them world premieres, on the internet instead of in cinemas. But we encountered an extremely friendly attitude from everyone in the film community, and so we realised that we should be more ambitious, and we changed our strategy: we would save as much of the programme as possible. We were aware that it would be difficult to keep films in competition if we couldn’t promise producers and filmmakers a sort of world premiere comparable to what they would have had if it had happened physically, with international press attention, international juries and availability of the film to buyers and sales agents online. But as we managed to ensure all of those elements, people could see that they would still get the exposure that comes with CPH:DOX.”

In fact, what they find is that most people aren’t just supportive, but grateful to have the opportunity to carry on their work. In the time available, they can get rights for public streaming in Denmark only, since that was the plan for the original festival, and they agree on a limit of 1000 tickets per film, after which it would be declared sold out. “Having produced festivals for the past 20 years, I found it quite exciting to be put in a situation where we had to rethink everything quickly. We stayed up all night planning in a heightened state of ecstasy, drinking cooking wine out of champagne glasses since we knew that after leaving there, we would all become locked down in our individual apartments,” Katrine tells me.

That night, they compose a letter to all delegates in which they promise a “digital solution.” Now they have to work out what that is.

Whatever that means, it is going to have to cover watching films; conducting Q&As and debates; five days of conferences; workshops with the CPH:LAB participants; a public presentation of the LAB projects; the co-financing Forum, and meetings with decision-makers for the Forum and LAB projects.

T-Minus Five

With no chance to recruit specialist technical staff, no precedent to look to, and everyone on lockdown, Katrine convenes a crisis meeting with myself and fellow conference curator, Sten-Kristian Saluveer, where we decide on a strategy to embrace online. This will no doubt involve a variety of platforms, but what we decide on for the conference programme should also work for the Q&As and debates.

I get in contact with all the speakers at the Art-Technology-Change conference to see if they would be up for moving the conference online. At this stage we have no idea what platform we might use for the conference – we will work that out if they say yes – which of course, they do.

I ask the LAB mentors if they would participate in online workshops. For the LAB project showcase, I contact Rene Pinnell to request teaming up with Kaleidoscope for an online pitch that would be streamed to the international XR community. With just a week’s notice he immediately agrees to step up with a wonderfully collaborative and positive spirit and I ask the LAB participants if they would be up for pitching their projects publicly online.

T-Minus Four

While the film team starts uploading the films, Sten sets about researching conference platforms and I enter the weird world of VR chat rooms with a group of XR enthusiasts calling themselves Embrace Online, who are testing various systems capable of creating virtual events in the wake of SXSW’s cancellation. This is definitely fun, although, in a space full of pink leather ninjas, dancing ducks, and introvert carrots, it’s really hard to find the other VR curators I’m supposed to be meeting here, especially since most people present seem to be teenagers.”

Photo:

Laura Loonstein

Photo:

Laura LoonsteinT-Minus Three

We regroup and discuss the conference. There are a few options.”I am not in favour of learning as we go, but we have three days to develop, test, and implement this plan”, Katrine reminds us.

Elsewhere in the festival, the team’s worst fears are being realised. It has become apparent that the Festival Scope film transmission system will not be able to cope with the increased demand of moving from servicing industry needs to also going public. Now, the film team has recruited specialised video streaming service Shift72 in New Zealand to work alongside them and are busy uploading the films all over again. As a result of this collaboration, Shift72 has now merged with Festival Scope to create a highly sophisticated system for digital transmission for festivals and without their combined openness and agility we never would have been able to pull this off.

My experiences with the Embrace Online VR group are eye-opening and make me more convinced than ever that within three years VR will be used for everything: remote working, conferences, demos, festivals, exhibitions. But that’s three years away and I can’t find a solution for replicating the immersive installations at the interactive exhibition that will work for enough people to make the effort worthwhile – yet – especially while I have the conference and LAB to plan. I look forward to seeing what my colleagues at the other immersive events will do with a bit more time to prepare.

T-Minus Two

Sten has managed to talk to every major tech platform in just a few days and has come up with a solution: “The key issue is embracing a culture of change. The CPH team was outstanding: management trusted us. Everything starts with the capacity of leadership and their understanding of what it means to connect to an audience. There is an implicit connection at DOX between the curatorial vision, the brand, and the audience. Plus we had this incredible effort and persistence from the conference curators. It was a time for mobilising people, to foster community and action.”

He suggests WebinarJam for the conferences and debates. It has a Green Room function which enables the tech team to prepare speakers before going live and allows playback from the cloud, which means that we can approach it like broadcast TV. It helps enormously that the tech team has plenty of experience in broadcasting.

We take a deep breath and we go for it, scheduling times for trials with the conference curators and speakers. We now have precisely 48 hours before it will be used for the Q&A of the opening night film. He reassures us: “The conversations we are having now will become standard for events over the next few months. Even if we deliver 70%, we are still making history. We are cursed by being the first. But people forgive us for that too.”

T-Minus One

In discussion with the other conference curators – Jessica Harrop, Patricia Finneran and Lauren Boyle – Sten and I agree on some parameters on how to use the platform. We decide not to restrict the conference programme to delegates: we might as well take the opportunity to go as broad as possible.

We share concerns about how long people could tune in without getting restless, so we settle on blocks of three hours, starting at 13.00 CET to make it easier on speakers and attendees from USA/Canada. If speakers are unable to join in live, they would be able to pre-record their talks – although if there is too much of this we might lose the feeling of a live event. We discuss how speakers need to create a quiet home environment and to dress their space to make it fit for broadcasting.

We decide to set up different channels within WebinarJam so the tech team can prepare speakers for their session while the previous speaker is already online. The speakers would be able to operate their own PowerPoint or Keynote slides, although clips had to be uploaded separately and it would work best if the tech team ran those. We are quite happy with our preliminary tech checks: the transmission quality is very good. We will be going live for the debate after the opening film in just 24 hours.

T-Minus Zero – Copenhagen, We Have a Problem

Our hearts in our mouths, we tune in at the allotted time for the debate after The Fight for Greenland, only to see this

Technical difficulties. We’ll be back as soon as possible.

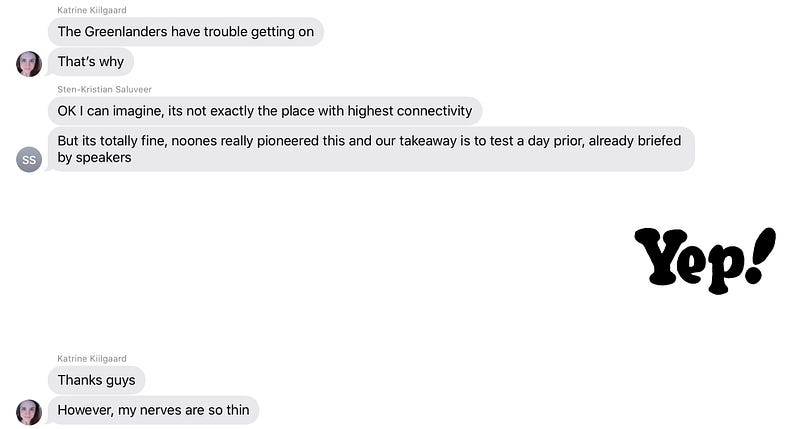

Katrine, Sten, and I are staring at this in horror in our lockdown homes, SMSing each other.

Despite Katrine not wanting to learn as we go, it’s exactly what is happening – but it’s not like we had much wiggle room.

We Have Lift-Off – The Public Programme is Go!

The next day comes around and the tech team has worked out some of the peculiarities of the system that didn’t work well last night. You can’t use the same link for the tech checks as for going live – you need to get people into the virtual space and don’t let them leave again, otherwise they are going to have trouble getting back in. Plus they have figured out how to relay the transmission to Facebook, so we will see how that looks this evening.

We regroup.

So that decides things. We will use WebinarJam as our virtual studio but direct the public to Facebook. This creates an added complication for speakers since they can’t follow how people are reacting on Facebook. Now we need to make sure that moderators will monitor the comments in order to cut and paste questions into the WebinarJam chat so the curators can see them for the Q&A.

Just a few days later, we have 75,000 people tuning in to An Evening with Edward Snowden, who is logging in live from Moscow for the debate to accompany Tonje Hessen Schei’s chilling and prescient film about artificial intelligence, iHuman. It goes without a hitch. The public festival is underway. And films are starting to sell out.

Next week we face five intense days of the international industry programme. Will they be as forgiving?

The Digital Conference

By now, in our frequent online planning meetings, my Danish colleagues are showing up with perfect hair and cool monochrome outfits against plain grey walls and I realise that I need to up my game. Time to move the furniture, take pictures off the wall, and create a somewhat decent-looking home studio space. And start wearing real clothes again. We have five days of conferences planned, in partnership with our friends at Documentary Campus.

First up is Jessica Harrop with Science Is Culture. Owing to time-zone constraints, she has a mixture of prerecorded and live sessions. She does a terrifyingly good job.

I’m up the next day, with the Art-Technology-Change conference. All of a sudden we’re on. My sessions are 100% live. It’s been so hectic that I haven’t had enough time to think about this moment. This is when I realise that this is nothing like a conference. It’s more like a radio broadcast that I am producing as well as participating in. I can’t see the audience and I can’t see the tech team. I can’t get the attention of the speakers without brusquely interrupting them. I am having some tech issues and I am sending WhatsApp messages to the team in Denmark while trying to hold up a conversation with panelists that’s being live-streamed on Facebook – although I can’t hear one of my speakers and there’s a time-lag. Thankfully, we reset in between each session – but so it goes on.

With each session, there’s a new challenge. It’s the most stressful thing I have ever done. A few years back, I managed the complex digital production for a live link from NASA in Houston to astronauts on the International Space Station, which was being transmitted on prime-time TV and a variety of social platforms to an audience of millions. This was way more stressful.

Afterwards, Sten, who curated festival day three, said, “We tend to be critical of kids on YouTube but they are the Jay Lenos and Oprahs of our times. I’ve developed so much respect for them.” Katrine agrees: “Unlike in a real conference, you don’t know who you are talking to. You tend to be solemn under those conditions. Then you come out of it and see that most other people are slouching on their sofas in pyjamas with a cat on their shoulder and you ask yourself, why did I have to be so serious?

My final session is an interactive film about online extremism, The Believers Are But Brothers, in which the audience participates live through WhatsApp groups. I finally have the hang of it – although Javaad Alipoor, the director, is ill with suspected Coronavirus and can’t participate in a planned discussion. (I am pleased to report he has made a full recovery.)

Cisco announces a 350% increase in internet traffic during the week of the festival, which causes problems for us, with the conference reliant on each individual speaker and curators having a decent internet connection. We learn that promised 24-hour platform support isn’t necessarily there in a time of international crisis. Even Facebook becomes overloaded on the final day and we need to shift over to YouTube mid-conference. We have to be constantly agile.

In terms of creating a festival feel, the downside of this system is that, although there probably is a community forming on Facebook, and we can see there are plenty of viewing parties planned, the speakers don’t feel part of that. That said, the conference programme reaches well over 95,000 people on Facebook and YouTube. Audience numbers average 650 viewing live, rising to an average of 5150 views per day (as opposed to a capacity of 200 in the physical venue). Our audience for the conference is 25 times greater than ever before. Now this is something we need to think about for next year.

What I now realise is that “live” within a digital context really means any time over that five-day period in which something remains active across international social feeds. The actual live moment is less important, although it provides necessary energy. In retrospect, I think one or two pre-recorded sessions would have provided some stability and extra time to wrangle any tech issues on the day.

Creating an Online Co-Financing Forum

At the same time as the conference programme, we are also running a couple of other high-profile Industry events that matter enormously to the individuals involved: the co-financing Forum for pitching documentaries and the final CPH:LAB workshops and project presentations.

The Forum is where documentary producers present work in development to funders and other stakeholders in order to secure finance, distribution, and exhibition opportunities. Projects are invited after a rigorous and highly competitive selection procedure and the event usually takes place in a closed room with a carefully chosen audience to protect IP.

Katrine calls some of the selected producers to ask whether they think we can recreate The Forum by holding a pitch and meetings online. The feedback is that most producers aren’t keen on an online pitch. For a start, no-one thinks that you can watch digital pitches for four hours, which was the way we had planned things for the physical festival. They don’t believe the shared screen facility on Zoom provides adequate transmission quality for trailers. WebinarJam, which we are using for the Conference programme, provides better quality but is more stable when viewed on Facebook and YouTube. Not only do most of the producers not trust those platforms with their IP, they also want to know who exactly is in the room. So we redirect our intentions to only hold individual meetings. We give producers the option of creating a recorded pitch, which we make available, along with the trailer and catalogue, for the invited audience to review ahead of the meetings.

We arrange 450 meetings across three days and an additional 450 matches for the producers to follow up on individually. We use Zoom for the meetings and make sure that each is scheduled with enough buffer-time to account for technical mishaps, problems logging on, and so on. We ask each of the decision-makers to enter a common lobby where they are met by DOX ushers who direct them to their meetings in break-out spaces. That lobby becomes an unexpectedly social space, where people genuinely enjoy hanging out together. You never quite know who you will meet there. Our delegates really enjoy it and although it demands some additional organisational capacity, it is far more of a human experience than just clicking through to the one-on-ones.

It’s actually fun and many report that this is the first time they have felt part of something since The Lockdown. It is allowing us all to reconnect with our international network. In addition, Tine observes, “There was a strong sense of community responsibility to not let the business die down, so the meetings were very productive.”

Putting the CPH:LAB online

The CPH:LAB is the DOX initiative for bringing together artists and creative technologists to develop new forms of expression in documentary. We started with nine projects in an intensive workshop in September in Copenhagen, where we worked on story development, audience and platform, and the creation of a proof-of-concept prototype. Now, after ongoing mentoring sessions, the creators were due to return to Copenhagen to discuss the financing, exhibition and distribution of their projects and to present them to the international industry.

It is relatively easy to run the LAB workshops on Zoom by creating group sessions for mentor and peer review of the project presentations ahead of the Showcase on Kaleidoscope in a few days. I’ve already done heaps of this sort of online mentoring in the past, so it doesn’t feel at all unusual.

The Showcase of the projects on Kaleidoscope ends up being quite a lovely event. Kaleidoscope essentially integrates Zoom into its own online platform, which works better for this kind of pitching than Zoom by itself. By going online we can invite more people than we would have been able to do in real life, both to the pitch panel itself as well as to watch along on Kaleidoscope.

There is a strong connection to a vibrant and engaged community here, which is very much due to the vision and collaborative spirit of Rene, Ana, and the team. The panel is generous with their market intelligence and offers of support to the pitch teams. Meanwhile, there are 600 people watching and commenting online. They are engaged and vocal and I am able to weave some of their contributions into the conversation. It is very useful for the pitch teams to be able to watch the session back online afterwards. We can send them the comments that came in via the chat, along with a list of all the people who watched the pitch, so that they can follow up.

Most of this is more than we would have been able to achieve in a live-only event. The following day, the creators have individual meetings planned in parallel to the Forum.

There has been so much energy and support and a lot of serious interest shown in the projects and this is enormously gratifying and fills me with hope. Nonetheless, coming down with a few gins in a Zoom Bar afterwards, I can’t help but miss the magic of the meetings that happen after these events in a real bar or cafe, where so much unexpected business happens and destinies become intertwined.

My next challenge is to devise this year’s LAB. The September event was intense and interactive, with plenty of face-to-face brainstorming and a ton of shared equipment. What is the version of this that will work under present circumstances?

Was it worth it?

It was far from perfect but absolutely YES.

In the end, the festival was able to run 150 out of the planned 220 films, along with 20 talks and debates to engage civil society; plus five days of conference programmes and three days of a very productive industry programme. We even managed to make four of the works from the interactive exhibition available to Danish audiences (Suvi Andrea Helminen’s Flux; Jakob Kudsk Steensen’s Deep Listener; Mikas Emil’s Where’s My Shadow, and Francesca Panetta and Halsey Burgund’s In the Event of a Moon Disaster).

The festival viewing period was extended as more and more films started to sell out. “Sold out” films meant people moved on to try something else. The festival has reached more of the country than ever before. Audience numbers are high – higher even than ticket sales suggest since streaming services tend to average 1.7 viewers per stream, so the reach has been extraordinary.

And there could be lasting consequences. Tine says, “Although normally we wouldn’t be able to show films in this way due to rights situations, it meant a lot of people discovered what are really challenging non-fiction films that would never be on public broadcasters or American streaming platforms and this might change the film landscape here.”

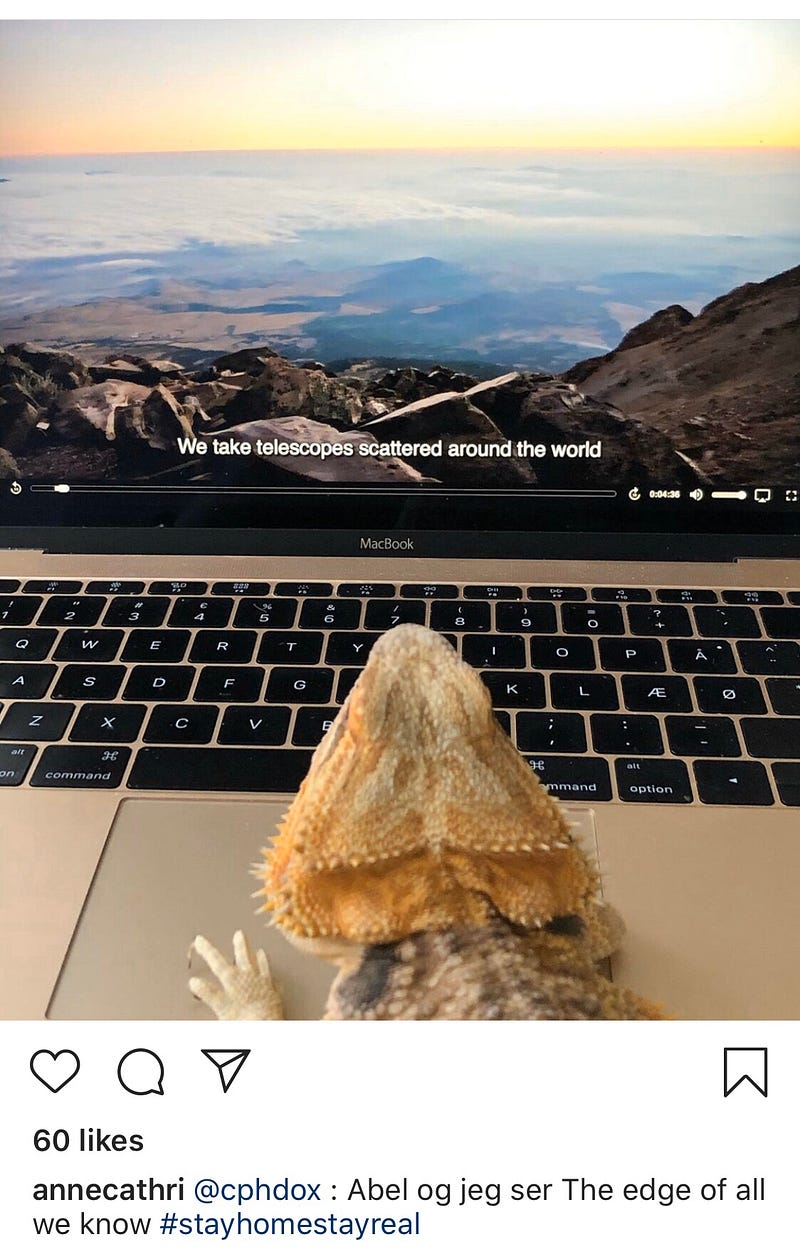

The festival has received a lot of press coverage. The Danish population and the international industry seemed to be amazed at what we were doing and were incredibly supportive. The newspapers have been reviewing the films. There has been a lot of buzz on social media and the public even started creating their own “Stay Home Stay Real” memes showing their home cinema set-ups for DOX. Considering that we were all so worried that the city would turn against us if we had gone ahead with a physical festival, this was an incredibly touching response.

Photo:

Anne Catherine Sauerber

Photo:

Anne Catherine SauerberThis intimacy went both ways, as the DOX team started to reveal more than just a blank wall from home, for instance when Niklas and his daughters handed out the Next:Wave Award during the online awards ceremony. “It kind of says everything about how the event became much more intimate, because everyone opened up their homes to each other, virtually,” he said.

Photo:

Niklas Engstrøm

Photo:

Niklas EngstrømIn the end, there has been a lot of positive press for The Fight for Greenland and we were able to create the public debate around the film that it required: it is the most-watched film of the festival and remains part of the public discourse.

What about next time?

If we were planning a digital festival from the outset, we would do things a little differently. Communications, marketing and outreach, and creating context around films is all different online and the film team didn’t have the opportunity to be strategic about this. Had Niklas known from the beginning that the festival would be only online he would have made a slightly different selection.

Katrine considers, “When a lot of what we do is to create public debate and when people aren’t so intimate, maybe you need to create an event that is different from a film and a debate. A digital version of the festival would be different in the future.” Sten’s advice is: “As festivals go forward, we need to consider skill sets and infrastructure. We need new skills as service designers and additional tech competencies. You need to plan back-ups.”

He reflected, “It is hard to foster a sense of community digitally. We didn’t brainstorm how to do that.” This year, we didn’t have the time for that but next time we will. Luckily for us, it is somehow in the DNA of the festival, so what carried us through anyhow was a community-minded attitude that was universally embraced. None of this would have been possible without the tremendous support of the local community and the industry, which Tine says has touched her more than anything else in the past 15 years.

People were grounded at home and you can’t compare it to other years, so you can’t take anything for granted. But Katrine wouldn’t go back to not doing an online component to the festival. “The wish to do an online DOX has been there for years. Necessity is the mother of invention and we had to do it. And it was an amazing test. With the film programme we reached people we never reached – 30% outside Copenhagen.” Even though the streaming tickets were half the price of the planned cinema tickets, they did very well. In fact, admissions have even exceeded last year’s record of 114,000, which means that in combination with various financial help packages that we will now apply for, there is a good chance we can survive into next year after all.

Mark Atkin is Curator of Interactive, CPH:DOX, and Head of Studies of the CPH:LAB.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.