History museums and cultural sites exist in part for the dissemination of information and experiences. Curators decide how best to illustrate the lives of bygone peoples and relay the significant events that changed them, shaping their narrative as it brings them to the modern day. One approach may be to communicate about a culture through artifacts (like the endless shelves and glass cases of the British Museum). A further step may be recreating the living space of someone who belonged to the time and circumstances, personalizing the circumstances of our ancestors’ lives so we might find points of divergence and commonality (like the Heard Museum or National Museum of Singapore). Finally, we might formally stage notable events in history (like the Shootout at the OK Corral), conduct ceremonies (the Changing of the Guards at Gyeongbokgung Palace), or simply adopt the dress and mannerisms associated with traditional culture (as with the Highland Games). Here, to varying extents, having an experience requires fewer stretches to the imagination as people see and portray a living history in which they may transition from observer to participant. Being immersed in history and tradition fuels our enthusiasm and, if we’re open, allows us heightened opportunity for personal connection.

Approaching

Colossus of Rhodes by Ship in 7 Wonders VR

Approaching

Colossus of Rhodes by Ship in 7 Wonders VRXR excels in producing digital copies of artifacts and architectural treasures. An Etruscan bowl, for example, could be recorded with a 3D scanning app, turned into an asset in a game engine, and infinitely duplicated in a medieval open-world VR game. Developers may also painstakingly model humanity’s long-lost wonders based on the artistic renderings of ancient texts, as was accomplished with Seven VR Wonders; here, visitors can sail past the Colossus or Hanging Gardens to see the grand works from all angles. Meanwhile, there is a push to capture culturally significant sites from around the world to faithfully preserve them in the case of human-made or natural disaster. One example is Cyark, a digital heritage organization that was inspired to preserve these sites after the 2001 destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan. Digital copies aid in the recovery process of a damaged site while openly providing immersive VR experiences.

The possibilities are now even greater with the release of VR apps that recreate not just the objects and places but entire events from history, be they mundane or monumental. Reliving history in this way is much more resource-intensive, as it requires the prior modeling efforts in addition to sculpting, animating, and voicing the characters present at the scene. Titanic VR, released last August, might be the biggest example to date, but there are a handful of other historical apps — many funded by local municipalities and released for free —well worth mentioning.

Waiting for

Supplies in Kokoda VR

Waiting for

Supplies in Kokoda VRKokoda VR recreates the lesser-known journey of an Australian reserve force trudging through the terrain of Papua New Guinea to slow the advance of Japanese forces during WWII. The historical documentation is done through old-timey newsreels and users are intermittently plucked from the cinema screen and dropped into a recreated scene from its history, which includes: sitting in a tent to fight off swarms of flies, waiting at an air strip for a drop as your supplies run low, and, finally, being in the middle of a battle as comrades to either side of you are wounded. As a history novice, I hadn’t known about these events before experiencing them here but, having been there virtually, the name “Kokoda” has a new resonance. I have greater awareness of surrounding events, and I’m not soon likely to forget them.

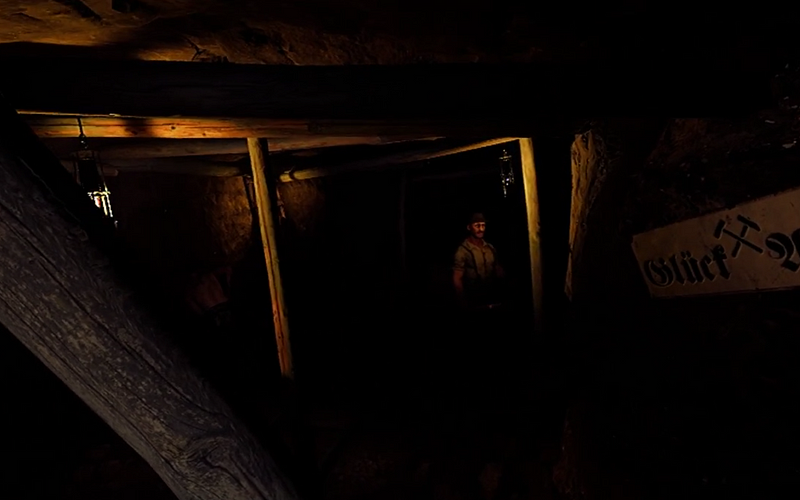

Brave the

Darkness of Meet the Miner

Brave the

Darkness of Meet the MinerMeet the Miner takes place in the same WWII era but this time in a German mine amongst men that suffering through conditions just as harsh as combat. The historical context of the story is again shown through live images and narration on a newsreel; finally, you descend the coal mines as a new hire. The men share your downward elevator joke with each other, both humanizing them and introducing emotional stakes to the experience. You are briefly trained on how to do the job of coal miner and do it for a few minutes out of what would have been, in reality, a grueling day, until you and your colleagues are faced with the risks associated with mining and work quickly to overcome them. Meet the Miner also gives heightened perspectives on lives throughout history and an appreciation that the standard of living, for many, has improved since then.

Scenes from

Vivez Versailles

Scenes from

Vivez VersaillesVivez Versailles is a history experience in VR that encompasses two somewhat major events in the famed French palace. The history of the palace and its present nobility are told from within the courtyard as you people-watch and eavesdrop on its inhabitants. Though the narrative tone of the history app is indulgently self-aggrandizing, the two main historical incidents covered in the experience remain interesting and, to my 21st century ears, comical. As you learn about the visiting ambassadors of Siam in the time of Louis XIV and a bizarre costume party put on by Louis XV, we experience the contours of Versailles Palace and the customs of nobility at the time. This education on France’s royal past is done through word, picture, and direct observation.

Scenes from

Timelooper

Scenes from

TimelooperApart from events that are being individually recreated for VR, there are efforts in mixed reality to use present-day reality as a canvas on which to place scenes from history. Timelooper is an app going to several of the world’s landmarks and placing a historical scene on the existing locations so that the past may be reborn. From New York’s Time Square to Ephesus in Turkey, this scene includes actors in historical dress re-enacting a ceremony, important event, or daily scene, which would give visitors a greater understanding of the people who lived there and their relationship to the place on which they stand.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more about our project here.