Image

courtesy of i2 media research limited

Image

courtesy of i2 media research limitedYou, me, and Judi Dench… and maybe a hot priest

We hear the word “immersive” so much nowadays, spoken as if it’s a new concept that has suddenly entered our world. That’s not to say what it represents isn’t “new,” but I think one of the first forms of immersive experience in cultural spaces is centuries old: cathedrals and churches. Story was etched into the walls and windows with the tools available at the time: The combination of song and stained glass windows with the light reflecting into the space, changing according to the time of day, temperature or weather. The sound of the human voice bouncing against the acoustics of stone and wood.

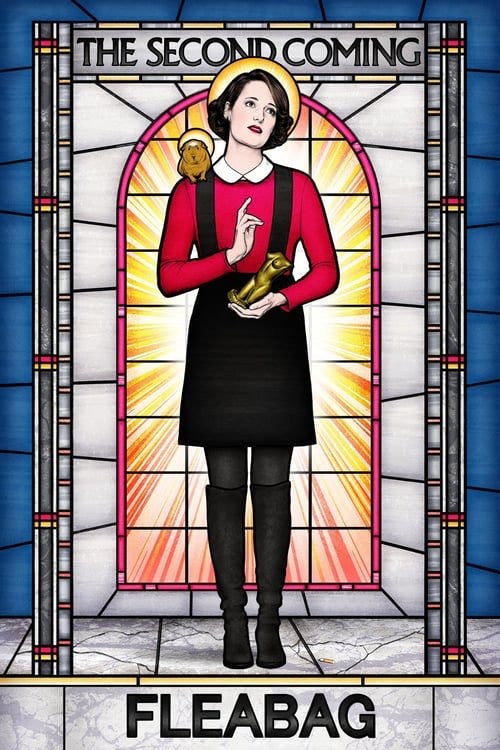

My religious knowledge is limited and only really engaged in the presence of hot priests, per recent streaming hit Fleabag. But I imagine sitting in those spaces reading the lines of code written into sand and glass in languages I cannot read. Those centuries-old ideas inform how I think of immersive experiences today.

At the Royal Shakespeare Company, my remit is to bring together artistic partnerships and imagine the future of theatre by exploring how we can create immersive experiences using new tools and technologies. When you visit Stratford-upon-Avon (which I hope you will) and come into the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, in the foyer, you will walk across the floorboards from our old stage, before a 2010 transformation. It’s an introduction to the building, to what you’ll see when you go into the next layer, which is the auditorium: A space which changes according to the story it is telling and builds worlds for performances to happen with a different audience every night.

Some people know the history of those floorboards, others don’t. It’s a subtle and simple reference, but there is no denying the ritual of having memories inscribed into that foundation — the actors who’ve performed on them and now the public who’ve walked on them. Whether that’s you, me or Judi Dench — cultural spaces immerse us.

Image

courtesy of Royal Shakespeare Company

Image

courtesy of Royal Shakespeare CompanyIn Western tradition, cultural space has been defined by a social hierarchy and rendered visible through buildings — theatres, museums, music halls, and galleries. But what if a “cultural space” could be anywhere? What if anyone could define a cultural space? Could your home be a cultural space? Could your phone become a cultural space? How does that differ from an entertainment space? Or does it? Could we use your floorboards? Your tables, your walls, or your memories for those immersive experiences? Maybe you’d welcome me and Judi Dench into your home?

If it were no longer defined by a social hierarchy, could cultural space be defined by us together?

Image

courtesy of Magic Leap

Image

courtesy of Magic LeapOver the past few years at the Royal Shakespeare Company, we have experimented and delivered a range of experiences that explore these questions.

Our latest piece in partnership with Magic Leap was a volumetrically captured performance of the famous Seven Ages of Man speech from As You Like It by Shakespeare, performed by Rob Gilbert with music composed by Jessica Curry. With this project, we thought about the stages away from our buildings, in your home and other places theatre has not traditionally been performed, and how we could immerse ourselves in the audiences’ space.

The work was showcased at Magic Leap’s LEAP Con in 2018 and premiered at Sundance’s New Frontier programme in 2019. Audiences of three to four people experienced the performance through Mixed Reality together, standing, sitting, being with the performer and seeing each other. Audiences moved like a flock of birds — connecting together with the rhythm of the performance and at points stepping out of formation to explore. The immersion and connection was defined by some of the best storytelling technology there is — the actor.

Image

courtesy of Royal Shakespeare Company

Image

courtesy of Royal Shakespeare CompanyIt’s no secret Shakespeare and his contemporaries broke the fourth wall with asides from actors asking audiences what they should do. They would give their truth and break from their world into the audience’s world for a moment. As we become the Fleabag generation, Shakespeare still travels with us. Fleabag’s look into the camera, a teasing glance, an opinion, a prediction: her relationship with us makes us feel special. She is ours and we are hers, and we are invested.

But what about him? The hot priest? We invested in him too. He’s the only character to get close enough to Fleabag to see her come out of their world and into ours. He holds her heart but he is not ours. She owns the key to that relationship, when he wants to know where she goes when she’s with us and acknowledges us in their story. We want to speak to him at that bus stop. Change a future. But, instead, we make up their future stories, and deconstruct meaning and code on social media feeds as we bear witness and share opinions, saying it’s our hearts that are also broken.

Technologies are now regularly helping us discuss story, character and also re-imagine cultural spaces and experiences, whether that’s a volumetrically captured performance on your table-top shown through a mixed-reality device or converging our virtual and physical worlds.

Institutions are exploring the many ways we can create those immersive experiences in their own space but also for you, with you and on your stages. It’s different from the broadcast model we have seen thrive in the 20th century. This content is circulated and distributed and unique to the platform it’s experienced on. It can be amplified, built on and experienced together in real-time.

Our challenges are myriad. We wait for the technology to keep up with our imaginations, so we can dive into a story or a space that we aren’t physically at and when we do attend them — use the technology — AI, data and connectivity to create a more personalised, immersed set of experiences that take those floorboards further.

Image

courtesy of Royal Shakespeare Company

Image

courtesy of Royal Shakespeare CompanyBut. Arguably the focus in recent years has been thinking with a “technology first” brain, often missing an audience-first perspective. Start with your hands and what you hold. Start with what you can see and who you’re with. Then bring the story into that space and use the tools that are necessary to help make that happen. Make the rituals you need to define and enliven the space to go to where new communities congregate and converge.

Image

courtesy of Royal Shakespeare Company

Image

courtesy of Royal Shakespeare CompanyBuild on what we know. We assume that in conventional theatre we are not interactive or immersed. However, every cough, sigh, laugh, silence, and tear is a connection; we don’t need to look at each other to be present together. Our presence is felt by the actor and audience. We experience this, and create worlds in time and space. Those real-time experiences can now happen across multiple spaces and stages through new technologies. Let’s take the volumetrically captured performance further, give the audience agency and enable them to use their senses within the piece — touch, smell — become more meaningfully immersed.

The tools we have now are bringing us closer and closer to being in and making those stories together and sharing them across multiple stages. Maybe we’ll save a few heartbreaks by getting closer to the hot priest or maybe we won’t. But think of the adventures we’ll have if we break all the walls and invite you to touch and change not only the world you’re in but what you do has an affect on someone else’s experience.

Could you play a part from your home in a play in Stratford-upon-Avon? Can we make a narrative for you, persistent in nature, like the world you inhabit, which is still there for you when you come back to it? Physically this is true, the coffee cup or the book left on the table. So let’s think about the virtual world in this way.

This is what we are exploring in the Audience of the Future project — a consortium of 14 partners all dedicated to exploring the future of live performance. Prototying and testing through innovation and a diverse range of people all with unique superpowers, committed to finding new sustainable ways of making this work.

The next frontier: Your story, your experience, immersed in your own narrative world in your time. A narrative you can come back to every time you come into that space — that can speed by more quickly or last longer than a conventional play or performance. Content that finds you. Content that remembers you. Content that responds to you. Imagine if what you touch moves in the virtual world. Your interactivity is experienced through the variety of senses.

As curators of cultural spaces, we are thinking of audiences all the time—when you’re with us and when you’re not. How do we connect with you and come into your world? The immersive experiences curators are making are not just about space but time and how we connect physically and virtually in the moment. How do we create those rituals that make you feel you are with us and also outside of your everyday? How do we make you think, and how do we move you?

We no longer expect you to come to us — we want to be with you, sit with you, and — whether it’s you, me or Judi Dench — be together.

This piece is part of an issue of Immerse sponsored by the Knight Foundation in conjunction with Knight’s call for ideas to advance immersive arts experiences. Open for applications through August 12, the call offers recipients a share of $750,000 in funding, as well as optional technical support from Microsoft. Learn more.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.