An interview with the creators of Ear Hustle, Earlonne Woods & Nigel Poor

Here’s a short take to help makers grasp the potential of co-creation: Check out any number of documentaries about life in San Quentin State Prison — from National Geographic’s San Quentin Unlocked (2006) to Louis Theroux: Behind Bars (2008) or any number of others that have been made over the years. You don’t need to watch the full shows. A few minutes will do to recognize a sort of outside-in caricature of violent criminals that audiences have come to expect. If you can relate to anyone featured in this traditional approach, it’s the guards (or, perhaps, the comic reporter).

Then, listen to Ear Hustle. It’s hard to fathom how this wildly successful podcast focuses on the same place — until you start thinking about how it was made.

Earlonne

Woods and Nigel Poor

Earlonne

Woods and Nigel PoorEar Hustle was created by Nigel Poor, an artist volunteering in San Quentin, and Earlonne Woods, who was incarcerated at the time. (In 2018, Earlonne was released from his sentence by California Governor Jerry Brown and is now working full-time on the show.) Antwan Williams, also an inmate, helped create and produce sound design. As a result of this collaboration, Ear Hustle’s portrayal of life behind bars makes the listener feel as if the place shown in the above documentaries is a wholly different location and experience. Creating the show as an intentional partnership has clearly paid off: Podcast episodes have been downloaded over 30 million times, and episodes reach many thousands more through short-circuit radio in California’s state prisons, where Ear Hustle is also broadcast.

For Immerse readers, it may help to imagine Ear Hustle as a sort of This American Life in Prison. The podcast does its share of translating prison culture for the outside world. Listeners hear, for example, about “fishing” (sending messages and food packages between cells); the art of selecting “cellies” or cellmates; conjugal visits (spoiler: not terribly romantic); birdbaths (bathing in one’s sink); and lockboxes (backup food and supplies in case of lockdowns). But sharing this knowledge is always done through a lens that values and prioritizes those stuck inside.

In an episode on “looking out,” we meet Rauch, who Earlonne describes as looking like the “original Jesus Christ,” dreadlocked, and as if he is “he’s from the earth.” Rauch hangs out on Hippy Row and acts as caregiver to moths, spiders, and baby swallows. Many episodes look at different aspects of sexuality; we meet Lady Jae, for example, a trans woman who landed in San Quentin before prison policy changed to recognize gender identity. One episode I found particularly affecting features men on Death Row. Any words I’d use to describe it would ring empty, so… just listen!

I was thrilled to have a chance to interview Ear Hustle co-founders Woods and Poor by phone in late August 2019.

Can you talk about how the show came about? How did you two initially connect?

POOR: I started volunteering at San Quentin in 2011 through the Prison University Project, a nonprofit organization. I think it’s the only on-site, degree-granting program in the California Department. of Corrections. People in San Quentin can earn an AA degree. I went in teaching a photography class. The longer I was there, the more interested I got in trying to figure out how to do a collaborative project with the men inside. Much of my class focused on using photography as a bridge to talk about personal experience, and it became clear that there would be a fabulous storytelling project if we could figure out a way to work together. I met a bunch of guys, one of whom was in the San Quentin Media Lab, and he asked me to work on a film project with him. We got started on that, but it became way too hard…

Way too hard how?

POOR: Editing film is complicated, and you can’t take the raw footage outside prison, so it felt like I’d be 80 years old before anything was complete. Also, I’m not a filmmaker, I’m a still photographer. I started thinking it might be easier to try our hand at audio, which sounds funny now because I soon realized how hard audio is! But we started doing interviews with the guys inside with the idea that we’d play them on the closed-circuit station inside. That’s where I met Earlonne.

So this was a radio program internal to San Quentin?

POOR: Yeah. When we were working on that, Earlonne was pretty quiet. He was working in the background on technical stuff. But he somehow really stood out as someone I wanted to get to know better and work with. He produced a story on breast cancer for the radio project and I think that’s when we both started thinking that we could do something else together, something that played to our interests.

Earlonne, did you have any media experience before you were incarcerated?

WOODS: No. Prior to being incarcerated, I wanted to go to American Film Institute but I sort of fell out of everyday life and didn’t get my application in. After I was in prison, I was watching the Discovery Channel once during a lockdown and there was a show featuring the San Quentin Film School. Immediately, I’m thinking: “I’ve been to a lot of prisons but I’ve never been to one with a film school!” So, for 6 years I tried to get transferred to San Quentin. When I finally got there, I learned there was no more film school but they still had all of the equipment. The guy there invited us down and we’d shoot videos around San Quentin. Then Nigel Poor entered the picture. That conversation she mentioned moved from video to audio and the radio program that San Quentin launched — or I should say re-launched. There was an earlier one in…what? in the 50s?

POOR: Yeah, ha! There was a show in the 50s.

So the idea for the podcast come about through you all working together?

WOODS: We were doing the San Quentin radio shows for the local radio station. It was a specific format, something like 5 to 8 minutes. Nigel brought up the idea of doing a podcast so that we could do more long-form stories… but, of course, I’m saying, “What the hell is a podcast?” She was able to get some examples cleared, so she brought some in, like Snap Judgment. After listening to it, I’m like, “cool,” that doesn’t sound hard. Let’s do these stories and we’ll put them on the institutional channel,” the closed-circuit channel for San Quentin and hopefully one day we could have it in all of the prisons in California. That was our mission.

POOR: There was nothing wrong with the radio program. I just thought that, together, we could creatively birth a project and not feel hemmed in by a news format. I wanted to do something coming from the perspective of an artist rather than a journalist. Since we were creating it from the ground up, we created the rules for it. When you find someone you want to create with, that’s a real gift.

Where do your story ideas come from? You have very different backgrounds, so how do you hash out what form things will take?

POOR: We all come up with ideas. It’s very collaborative. I’m personally most interested in the small gestures, the everyday small stories that can speak to larger issues. When E was inside — it’s different now that he’s out — he was always ear hustling wherever he was, trying to bring out stories. We had some rules: We didn’t want to repeat ourselves, we didn’t want to do stories about programs or profiles of one person. I personally wanted to stay away from stories about reform or redemption, I feel that it’s such an overdone topic. We get excited about finding interesting characters… and stories that are varied in their emotions. Our stories can be funny, heartbreaking, scary, and charming all in one go.

Were the men in San Quentin interested in participating from the beginning or did you have to pull it out of people?

WOODS: In the beginning no one quite knew what we were doing. People weren’t up on how podcasts work. So, at first, we interviewed people we knew. As we were able to put stories up, and when family members started telling inmates about hearing the podcast, people started approaching us about stories.

POOR: We were under the radar somewhat. We’re both fairly quiet people but we had a plan about what we wanted Ear Hustle to be. Now, people are constantly approaching us with what they think we should do a story on, which isn’t always what we think we should do a story on. But it’s cool that at least inside prison it’s easy to get people to talk to us — except for correctional officers. It’s still tough to get them to participate.

Do they regularly get the episodes inside San Quentin?

WOODS: At first our mission was to have the inside population hear it. But at the time we were under an instructor who was slow to put it up. We’d have an episode done, but this person wouldn’t get it out. So, our episodes would end up airing in society first, and that would push them to put it on the institutional channel. The main population that I wanted to hear the stories was Death Row. Death Row are in their cells almost all day.

POOR: Now episodes are played in all of the prisons in the California Department of Corrections. And we’re getting emails saying, “When are we getting new episode?!” A guy came up to me the other week and said, “We need more episodes!” That’s the biggest compliment, to have guys inside asking us for it.

Have you ever had someone on the program talk who later freak out about it being so public?

WOODS: We talk to a lot of guys who are serving life. And people can be veerrrrry vulnerable. Sometimes they’ll open up and say a lot of stuff. Then sometimes people have to stop and think about how they’re going to need to go to the Board of Prisons… We have a portion who have been on the show and loved it, and then we have a portion who are old-timers who have probably been in the system 40 years or better. There used to be a prisoners’ policy where you couldn’t talk to the media. Ear Hustle became part of the media, so we couldn’t get them involved, though I’ve tried every tactic in the book! [laughs]

POOR: There are guys who won’t talk to us. But I will say, with Earlonne, because he was so respected inside, people would often respect his request. That helped a LOT. He just has that kind of personality, a special connection with people. We’re doing a story this season with a guy on Death Row. We had to talk to him 6–8 times before he agreed to do it. We weren’t badgering him, we just kept trying to get his attention and tried to earn his trust. We don’t mind taking a long time because we understand once a story goes out there, it’s never coming back. We both feel protective of people and want to make sure they’re good with what’s out there.

Do the two of you make most of the editorial decisions or are there others involved? Have you had a lot of debates where Earlonne wanted to include something and Nigel didn’t — or vice versa?

WOODS: Let me start this one off

POOR: I know what you’re going to say!

WOODS: Okay, what am I going to say?

POOR: You’re going to talk about the telephone… [Nigel laughs]

WOODS: No, I’m going to talk about the editorial process! Most of my best thoughts were edited out because they were my best thoughts, they weren’t the show’s best thoughts. So, when I listened to the whole thing edited, I would think, “yeah, you’re right, that didn’t have to be in there.” [laughs]

POOR: We work with Julie Shapiro from Radiotopia, our Executive Producer, and Curtis Fox is our senior editor, so they help us with scriptwriting. We have other guys inside, New York, John “Yahya” Johnson;, and Pat Mesiti-Miller, an outside producer who comes in and really helps the sound design team. We couldn’t do this without Radiotopia. No way. And having a good editor that you trust…

WOODS: When we first started, we had an editor and didn’t know how to use him. We was doing all of the heavy lifting, the cutting, taking forever…. But we figured out we could bring the editor in a lot earlier! [laughs]

POOR: Editors are invisible to the process but critical. Earlonne, I thought you were going to bring up the phone thing. Sometimes there are details I want to keep in a story because it’s so interesting but Earlonne is always the person who’ll hesitate and say, politically, it’s not a good idea. I’m not going to say we have to censor stuff, but we have to be careful.

WOODS: I wouldn’t say censor. We’re not news media, and people don’t necessarily have to learn everything on Ear Hustle. If someone learns how to make a knife in prison, that’s not something we do. If someone wants to learn about how drugs get in prison, that’s not something we cover.

Public radio is known for having a certain type of sound, a certain type of listener. How conscious are you of that expectation?

WOODS: Our initial listeners are prisoners. I’m not focused on society listening that much. I’m focused on how people inside are hearing these stories and how they feel.

POOR: Earlonne, would you be able to describe what a public radio sound is?

WOODS: Only verbatim from Nigel! When I get in the car, I’m waiting to hear BOOM BOOM BOOM, BAM BAM BAM. MUSIC. BASS! Nigel get in the car, there is none of that. There is talk radio.

POOR: When we started this, there was some talk of who would listen. And I thought, “I think everyone will want to listen! Not just the typical public radio audience.” I wasn’t being arrogant, I just thought: This is so interesting, who *wouldn’t* listen? And I believe if you look at our demographics, it’s very broad. There are people in prison, people related to those in prison, soccer moms, college students…

WOODS: Judges, lawyers, governors. What were our projections for the first season?

POOR: We were told we’d be successful if we had 20,000 downloads. One month in, where were we?

WOODS: Over a million downloads.

Whoa. Was that before California made it available in all prisons?

WOODS: We don’t get downloaded by the prisons. That closed-circuit radio. That doesn’t include those listeners.

Do the two of you have different specialties? Are there things where Earlonne is like, “I need to lead on this one…”?

WOODS: Nigel and I know who can get what. Nigel is the queen of those great followup questions. A great example is The Big No No, which is about the right and wrong way to fall in love with a guy inside.

POOR: It was a beautiful story about a volunteer who fell in love and married an inmate. After the story was just about finished I found out what the guy was in prison for: he had murdered his previous girlfriend. And, so, I realized we couldn’t put the story out without asking him about it. I was really nervous. It was really difficult. You could hear how nervous I was, you could hear how hesitant he was, but he really opened up and it was a very poignant, difficult conversation.

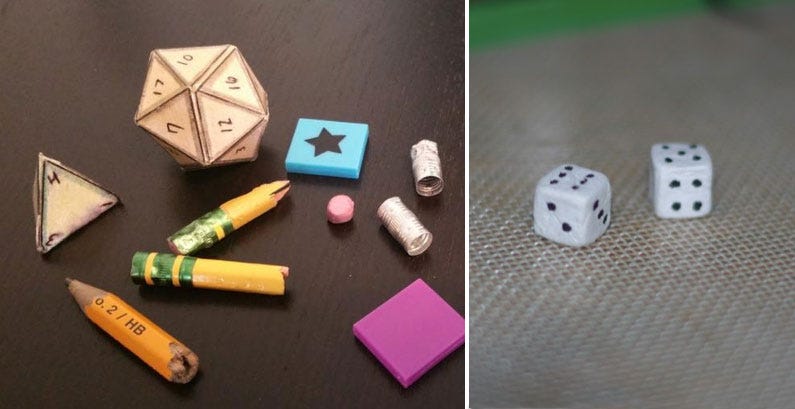

Plastic dice

are banned in many prisons, forcing inmates to get creative to play Dungeons & Dragons. Examples

of alternate randomizers shown above. The six-sided dice (right) were crafted out of toilet-paper.

Objects courtesy of Melvin Woolley-Bey (left), Gabriel R. (right). Photo by Elisabeth de Kleer, who

documented game play in a

maximum security prison in Colorado for Vice.

Plastic dice

are banned in many prisons, forcing inmates to get creative to play Dungeons & Dragons. Examples

of alternate randomizers shown above. The six-sided dice (right) were crafted out of toilet-paper.

Objects courtesy of Melvin Woolley-Bey (left), Gabriel R. (right). Photo by Elisabeth de Kleer, who

documented game play in a

maximum security prison in Colorado for Vice.One of my favorite segments was about Dungeons & Dragons — and how, at San Quentin, D&D is a game that brings people from different racial groups together. Is that unique in San Quentin or are there other games that bring people together?

WOODS: Well, we found out after that episode that Dungeons & Dragons is actually illegal in prison! [laughs]

Nooooooooo! I hope no one got in trouble.

WOODS: No, ain’t nobody get in trouble. But, to me, a prison should always support things that bring the races together. It’s a segregated environment, so if you have a game that brings people together, that should be good. But maybe prisons don’t want things that bring the races together. I don’t know. San Quentin is a different prison. At San Quentin, you will see individuals playing sports and other games together. In season 5, we look to go to different prisons, including maximum security prisons. I think the race conversation will definitely come up there because that’s what runs prisons sometimes.

POOR: Sometimes people say stuff about race inside that we cut because it would not pass on regular radio because of some of the language that’s used. I would like to not do that. I’d like to be real about how people talk in prison. I think people can handle that. Race in prison is not a topic that people run away from; it’s pretty in-your-face, I think much more than on the outside. But it’s not always couched in sensitive ways.

I wonder if it isn’t just as present in the outside world, just not as explicit…

WOODS: Prison is a reflection of what this country was, and what this country still is, in some pockets. But in prison it’s open. And in society it’s not as open. I don’t think people move forward in prison when they segregate. When the country was segregated, the prisons were segregated. When the country desegregated, prisons stayed segregated. That memo didn’t get to the prisons. When the prisoners figure out that to get along means to change the system, then the system will change.

This article is part of Collective Wisdom, an Immerse series created in collaboration with Co-Creation Studio at MIT Open Documentary Lab. Immerse’s series features excerpts from MIT Open Documentary Lab’s larger field study — Collective Wisdom: Co-Creating Media within Communities, across Disciplines and with Algorithms — as well as bonus interviews and exclusive content.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.