The Real Potential for Solidarity in Virtual Communities

As a period of escalating political dissent looms, activists, journalists, and the communities they engage are looking to digital tools to widen the reach and impact of their message. Whether via the immediacy of live streaming, the immersion of 360 video, or the network effects of social media, digital platforms offer possibilities for creating virtual communities around real issues. But it’s worth revisiting the question of whether the likes of Periscope, Facebook, or Twitter serve as a basis for genuine solidarity.

Many of those facing the militarized police in Standing Rock were moved to action as a result of an increasingly scandalous narrative carried primarily on social media. Videos streamed from the front lines — both from activists and independent journalists, such as Democracy Now!’s shocking account of dogs sicced on unarmed protesters — gained traction as thousands shared them in collective outrage. By the same token, when a man fired a rifle inside a Washington D.C. pizza restaurant in November, he was emerging from the tail end of what amounted to a transmedia fantasy narrative, given life among platforms such as Instagram, Reddit, YouTube, myriad comment threads and so-called fake news sites, reinforced within the feedback loops that our social feeds have become.

For better or worse, the multimedia, multimodal nature of today’s various digital platforms have shown incredible power to inspire, organize, and motivate people in the real world. Can this capacity be put to better use in supporting communities standing up to injustice or abuse?

Putting networks to work

During Brazil’s 2013 Vinegar Protests, Filipe Peçanha, member of the citizen journalism collective known as Mídia Ninja, live streamed his own arrest to some 5,000 people. News of the event spread fast and mobilized crowds to surround the police station where he was being detained. According to Peçanha, the police heard the roar of the crowd from deep within the station.

“They didn’t understand that it is not a camera, not a reporter,” Peçanha said afterwards, “This is a network.”

Such events offer compelling evidence that the connective, organizing potential of digital platforms can offer new and powerful means of engagement between concerned citizens and the issues that concern them. A mass of witnesses connected via live streaming video can indeed make their presence felt on the other side of the screen.

Mobil-Eyes Us, a project of activism innovation nonprofit WITNESS, explores how the organizing power of networks and the experiential impact of real-time, immersive media might be wielded on the front lines of activism.

One of their ideas is making the number of viewers for a livestreamed protest, vote, or negotiation visible to those being filmed. They also suggest an “Assembled Action” workflow, stringing together Google calendars, Meerkat livestreams, Twitter, and IFTTT applets — ‘if-then’ commands that integrate with and trigger a variety of services. Together, they could form a dynamic, automatic alert system that contacts and mobilizes people in real time based on their particular expertise for specific circumstances.

Slide taken

from Sam Gregory’s talk at TFI 2015 on Co-Present

Storytelling and Action

Slide taken

from Sam Gregory’s talk at TFI 2015 on Co-Present

Storytelling and ActionTechnology already makes connecting distant viewers to a critical event in real-time and in rich detail an easy feat. You can browse a map of the world and decide where and what to watch. If only you could then engage in more ways than simply observing, sharing or donating money.

“A fair amount of activism is about this intense experience we share as participants,” says Sam Gregory, program director at WITNESS. “But a lot of the way we try and motivate people is still quite abstract. We send an email saying ‘try and feel what it’s like to be this person who suffered X,’ and then we ask people to participate in a fairly generic action. It’s unlikely that the best use of anyone’s time is donating ten bucks or clicking something.”

Forget haptics — this is about making something happen

What if there were pre-existing channels offering qualified viewers of a police confrontation the chance to contribute legal advice, or real-time translation, to report what’s occurring to local civil rights organizations, all the while knowing that they could contribute more if they wanted to? Deepening the capacity for making a difference could draw more people in, and would be felt more acutely on the other side of the screen.

Forget haptics—this is about making something happen. Through networked platforms, there is a range of possible engagement that could redefine the term “armchair activism.”

Comparisons

of the features of telepresence (left) with co-presence (right), from the IFTF

blog

Comparisons

of the features of telepresence (left) with co-presence (right), from the IFTF

blogThis all points to a mode of digitally mediated interaction dubbed co-presence. Through live streaming, video chat, and 360 video (which can also be streamed live) we get whiffs of co-presence. It’s distinct from telepresence in that not only does one feel, sensorily, that they are sharing a space with someone, but also that they are enabled to participate directly, in ways that transcend what’s possible in person. Rather than sharing a moment, even if virtually, you’re also sharing an object of action. This is related to what the Institute for the Future calls “attentional proximity.” According to the IFTF the technology is already here, all that’s missing is the plan for leveraging digital platforms to support these kinds of interactions.

One’s body is its own form of invaluable, non-counterfeitable civic currency, but it’s not always available to offer. Yet our minds, skills, time and effort are also of great value and can be invested in many new ways thanks to digital tools. The devices in our pockets and on our desks afford us windows to the world. What’s needed are ways of reaching through them to lend a hand.

Engagement vs. involvement

While on trial for copyright infringement, Pirate Bay spokesman Peter Sunde was asked why he and his partners chafed at using the term ‘IRL’ — In Real Life — when recounting the story of how they met.

“We don’t like that expression,” he replied. “We say AFK, Away From Keyboard. We think that the internet is for real.”

No doubt, what is experienced and expressed online carries tangible consequences. Digital platforms have proven instrumental in sparking movements that spill into the streets. But in theses cases the role of technology tends to recede as the ephemeral, emergent, fast-twitch connections give way to the grinding mechanics of analog organizing. Easy as it is to confuse new forms of media as revolutionary messages unto themselves, movements live or die on what happens outside of the screen. Solidarity is a commitment, not a gesture.

“Most of the people who were marching in Egypt didn’t even have access to Facebook, yet it was called the Facebook Revolution,” says documentary filmmaker and sociologist of new media technologies Sandra Rodriguez. “If you follow the salesman’s pitch discourse, it becomes, ‘How can you use social media to make sure we have a political or social impact?’ Cinema, documentary, radio, even TV shows and music were really, really important in the social movements of the ’60s, but there’s no way you can prove it’s the TV that changed the social movements.”

At the end of the day, any form of solidarity pertains to something that happens in physical space

What’s real is what these mediums carry. Maximizing their strength as experience delivery systems or creating ever denser networks, while valuable, is not what will define their value as transmitters and amplifiers of solidarity. Indeed, quite small — but organized — groups of people have proven powerful agents of change over recent decades. As Bill McKibben reminds us, no more than 1 percent of Americans ever participated in a civil-rights protest.

McKibben goes so far as to describe peaceful protest itself as a technology, perhaps the most important of the 20th century. Protest is both medium and message. It’s a practical system for organizing people and directing their energy effectively. Accordingly, there’s something to learn about the movement-sustaining potential of digital platforms from peaceful protest.

Protests are an invitation to take part in a larger movement, manifested. At their most effective, they are issue-focused and form-flexible, built around a principle of open inclusion and broad involvement (and, of course, nonviolence). Ideally, they offer opportunities for long-term, deepening commitment rather than seeking to cause maximum immediate impact. That’s not exactly the digital M.O.

Facebook

users can now interact with events in real time, as in the livestreamed police shooting of Philandro

Castile

Facebook

users can now interact with events in real time, as in the livestreamed police shooting of Philandro

CastileThe Black Lives Matter movement offers another interesting example. BLM organizers managed to forge and maintain a relatively horizontal network across various social platforms — driven in large part to a surge of horrific videos of police violence in 2013 and 2014 carried by those very platforms — which has created a meaningful and shared sense of purpose among those who identify with the movement. However, on the whole, the network simmers while smaller groups within the movement activate in response to specific, local issues. Standing with gives way to standing beside.

At the end of the day, any form of solidarity pertains to something that happens in physical space — a lack of food or clean water, beatings or killings perpetrated by state power, a lack of jobs or the theft of resources, and so on. While there are many interesting technical possibilities for providing material, moral and other forms of support through networked devices, lasting community, accountability, and therefore solidarity are generated where people meet face-to-face. The opposite form of unaccountable solidarity looks something like a sea of Pepe the Frog avatars. Trying to mobilize such a community IRL — sorry, AFK — can get messy.

Productively channeling the emotional heft of something like Standing Rock — to which most people could not contribute more than what was available on their screens — requires offering ways for people to participate and feel directly invested in the issue. That means striking a balance between the larger movement and particular issues which people can actually (as in physically) reach.

What if instead of suggesting thematically related pages to distraught viewers of distant abuses, Facebook connected them to protests scheduled to take place nearby them? Or directed them to their representatives’ inboxes, and provided names and addresses of local advocacy organizations that need bodies?

The revolution will not be Facetimed

Admittedly, this is unlikely. Facebook’s self-assigned mission after all is to connect the world, not correct it. Maybe that’s for the best, because real change doesn’t descend from the synthetic hilltops of Silicon Valley, but from the grassroots up. Facebook and its ilk are probably more revolutionary in their capacity for commodifying attention and outrage than organizing and applying it productively to social ends. And anyway such platforms are prone to various forms of censorship.

Even the range of expression itself is defined by the platform owners. Such bounding of permitted speech is pretty much exactly what protest is designed to subvert and rebuke. These compressed expressions of support or outrage may be less like the virtual spaces unbound by the architecture of the public square than the digital equivalent of a free speech zone.

Breaking out of the strictures imposed by platform owners is key to their use as tools of genuine solidarity and revolution. Small groups of people demonstrate that democracy is in the streets by seizing them in peaceful protest, to great effect. So too can they seize the formidable power of networks and digital platforms for themselves.

There is great potential in mesh networks, for example. Comprised of local, line-of-site connections, they allow communities to operate and define their own telecommunications infrastructure. This offers communities greater agency and control over the very means by which they communicate. Why use a corporate-owned telecom to talk to your neighbor anyway when you can build and use your own, more resilient network?

In New York City, in preparation for Trump’s America, rapid response networks are forming to direct aid to those who would prefer not to call the authorities — whether for domestic or racial violence, ICE raids, basic medical needs, and so on. Small groups of citizens are building their own operator networks, using cell phones, anonymized and encrypted IRC and group chat platforms, and other tools, while providing training for first aid and self-defense. Though smaller in scope, they offer a more reassuring network for those in need of solidarity and support than anything funded by venture capital.

Stepping up the ladder of engagement

All of this is not to say that there is no role for what seem like small, even meaningless gestures enabled by the gargantuan digital platforms. Everything fits within a spectrum of engagement.

“I’m not dismissive at all of what people think of as clicktivism, things like turning your Facebook profile pic a different color, or signing in at Standing Rock, because they’re simple ways in which you can start to participate,” says Gregory from WITNESS.

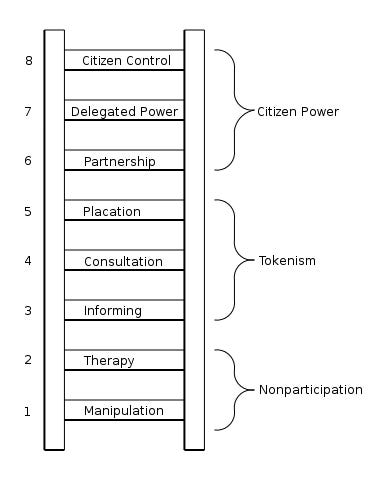

Sherry

Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation

Sherry

Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation“It’s a classic activism idea of the ladder of participation. In some ways we’ve stunted that ladder in a lot of online activism by making it very basic, not really providing enough steps up, and not making it very experientially connecting. That connection is really important if we do it right, to feel closer to frontline communities, to stand in solidarity. That’s not the same as having empathy or pity. It’s the idea that, particularly using these forms, it’s possible to stand with people, not just take actions for people.”

Technology can and should reduce the impediments to those far from a front line who wish to contribute more than cash or a floating thumbs up. Real-time, immersive media can connect people to an issue in more personal, visceral ways. Networked platforms can channel that connection into a number of productive ends in real time. People can build their own networks and tools on what is now a ubiquitous range of devices and platforms.

There is much potential for encouraging lasting and meaningful forms of solidarity on digital platforms. But any technology will only be as effective in generating change as the movement it channels.

Read responses to this piece

“Real solidarity” Isn’t the Problem — Effective Action Is

Beyond Tweets and Streets: Standing Up to Hate

Immerse is an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.