Covid-19 has hit the emerging technology storytelling community hard. From all corners of the industry, we are feeling the impact of cancelled festivals, whiplash from the heightened fear of contaminated devices, and the intensifying uncertainty of what is to come.

Will things return to normal? What is the role of festivals when more than 10 individuals cannot meet in the same space? Can we still have meaningful gatherings and build community? How do we fund and create our emerging technology work?

These next few months will require us to push ourselves to think in innovative ways to create work and tell our stories. We will need to think beyond the headset to find funding, to manage our teams, and to have human connection while maintaining a social distance.

One good thing? Our industry is built on innovation. We have never had a road map on how to create our work, so uncharted territory is the norm. But we need to remember to help each other, and to ask for help when it’s needed.

I had the opportunity to speak with members of our emerging technology community who are dealing with lost opportunities but finding ways to create and invent new ones. Each person has unique advice and insight into their experience, how they are continuing to make work and how they plan to move forward:

Stuart Campbell (Sutu Eats Flies)

Sutu (aka Stuart Campbell) has created 360 animated virtual reality films and interactive comics. He is the co-founder of EyeJack, an Augmented Reality (AR) company. This year he relocated from the Australian Outback to Los Angeles. I spoke to Sutu via What’sApp from our apartments across town where we were both sheltering in place.

Sutu was set to premiere three virtual reality films at SXSW this year. On top of that, he had invested about $10,000 into an installation being built in Texas which is now on hold indefinitely.

As someone who is used to working remotely from the Australian Outback, it’s not working from home that worries him — it’s the cancellation of events. EyeJack does location-based events, including AR murals and activations. Four of the company’s upcoming events have been cancelled. Even with pivoted pitches toward creating AR face filters (like those used on Snapchat) and other remotely accessible projects, the biggest struggle the EyeJack team is facing is that businesses and clients are not keen to sign off on any new projects during this period of unease. In order to keep their international team of remote workers employed, the company needs projects in the pipeline. Without contracts signed and next steps laid out with clients, it’s hard to feel secure.

Outside of hustling to keep his company afloat, Sutu is using this time at home to focus on skill-building. He is learning Blender and Medium as a way to make the most of this time at home. He wants to make sure that he and his team are well-prepared for remote working, as it is uncertain how long this will last. He is optimistic and sees a silver lining for the VR community in all of this chaos — now is a great time for the world to embrace VR in their homes and Sutu thinks there might be opportunities for artists to license their work. Until then, he is pitching constantly and using this time to set up conversations with potential clients. Audiences are home on their phones and looking for high-quality and fun interactive entertainment.

Alethea Alvramis

Alethea C. Avramis works at the intersection of experiential and interactive content, and traditional filmmaking. She is currently an LA–based content director for immersive entertainment company Meow Wolf.

Outside of her work in immersive content, she has been working on a film for the last seven years, which was set to premiere in Greece in early March. The festival ultimately shut down the day she was meant to travel internationally, three days before the festival was to start. She is saddened by the loss of this opportunity to share her film with the world. Instead of being in Greece, she’s back in Los Angeles. I spoke with Alethea as she took a walk to get some fresh air and she told me about what she’s learned from the experience.

Her advice to festivals: Facilitate connections between creators and press that would normally happen in festival environments. Right now, filmmakers urgently need press for their projects. If a film was accepted to a festival but there was no press, did it go there at all?

Getting media coverage is a necessary step in getting distributions and sharing a film with the world. Festivals could help out filmmakers by making introductions to journalists, sharing writing about selected films and immersive works online, and helping to create buzz for the projects that will allow the work to thrive.

Makers have many questions at this moment: If a film has been accepted to a festival but was never screened at the festival, how does this impact future festivals the film may travel to? Would it be a premiere? How will this be handled by festivals internationally?

Alethea plans to wait out the Covid-19 storm before making any major distribution choices. During this time she plans to think through what online distribution could look like for her film.

Kate Parsons and Ben Vance (Float)

Kate and Ben are the immersive video artists behind FLOAT LAND, an LA–based collective focused on the intersection of art and interactivity. Kate also teaches Interactive VR at Pepperdine University. As artists, the closure of public spaces and events has had a major impact on the way their work is experienced. I sat down with them via Skype as we drank our morning coffee in our respective homes.

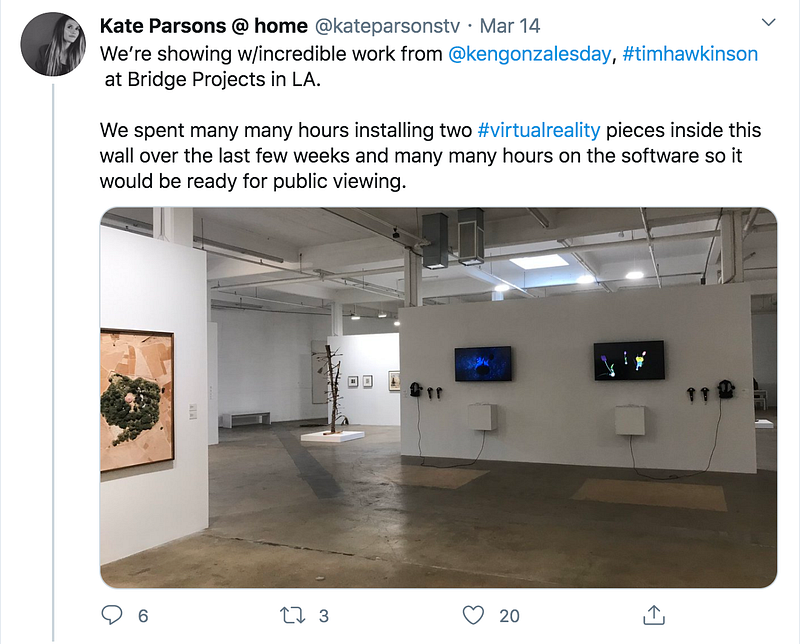

That week, To Bend and To Bough — a fine art exhibition at Bridge Projects Gallery in Los Angeles — included a virtual reality installation by Ben and Kate. As many interactive technology and VR creators will understand, it can be extremely difficult to get your experiences into fine art spaces, so this was a big achievement for them. The pair had put a lot of time and resources into the launch of the show, which was to be open to the public for the next two months. With wipes and hand sanitizer available to all, the show was up for the day of March 14th before closing to the public.

While the show was still open, the team was able to share its installation with audiences in New York City through a virtual tour. The tour had been organized as a way to share art with individuals across the country — conveniently, this also allowed folks self-isolating at home to see the work. They hoped that they could continue to run virtual tours from the gallery as a way to share the work while limiting guests in the physical space. Now that too is impossible.

Kate had been planning to present years’ worth of research at this year’s SXSW festival in Austin, Texas. She found out about the cancelled festival as they prepared the launch of the Bridge Projects show. Speaking and presenting in major festivals can gain artists exposure and future work. While the loss of this experience does not translate into monetary value, it impacts her future projects and income.

At the time of chatting with them, classes at Pepperdine had all moved online, posing challenges for Kate as to how the students were going to get hands-on interactive VR lessons via a virtual platform, and students were being asked to vacate their dorms and head home. She discovered that using a platform such as Twitch to stream VR lectures could help address the problem.

Ben and Kate hope that organizations and festivals with available resources could use these funds to support artists who are no longer able to make an income. What are other ways organizations and festivals can support their communities right now? Femmebit, the festival Kate founded, plans to stream content from its artists online in the upcoming months.

Arnaud Colinart

Arnaud is a Producer of immersive entertainment and animation at Atlas V, one of Europe’s leading virtual reality companies. It was founded by Paris-based VR creators Antoine Cayrol, Pierre Zandrowicz, Arnaud Colinart, and Fred Volhuer. I spoke to Arnaud over Skype from his teenage bedroom. During the Covid-19 pandemic he had relocated with his wife and children to be with his mother in his childhood home.

Despite having plans for projects to premiere at now-cancelled festivals, Arnaud is optimistic. He figures that for now, their company has enough work in the pipeline to keep operations moving as usual. Their team is used to working remotely and with collaborators around the world so that new restrictions do not daunt them. Priorities for Atlas V during this time are to continue to pay the freelance team. If the production pipeline can continue as normal, Arnaud hopes that they will be able to move through these challenging times unscathed. He recognizes that Atlas is a young company, in a young industry, dealing with a very experimental platform. The risks for his team are quite high.

One of the challenges he sees is how to have creative breakthroughs with artists in the development and writing phase that are crucial to the success of a project. While most production can be done remotely, these breakthroughs often occur face-to-face and in-person. Projects that are already in production and have made it past development are not at risk; it is the projects that they are just starting, or collaborations that are just forming. That moment in the life of a creative project is so important, and that energy often sustains the project across distances as the team’s work toward a shared goal. How will work be energized without that spark of connection?

Personally, he notices that the current climate (with the addition of working from home with two very young children) is not great for his own focus. Script reading does not come easy during a crisis.

Atlas V is in a relatively good position because early on the company decided to diversify, adding distribution and creative development to production work. Their team has produced a number of successful VR projects, and this body of work could be made available for streaming and distribution online. The team has noticed a significant spike in audiences streaming VR content, with downloads multiplied by 100. These downloads are mostly free, but it is a sliver of hope for virtual reality creators and the industry as a whole. There is interest in emerging technology experiences during this time, and audiences are craving high-quality content.

Antoine Cayrol, who leads Atlas V’s sales, has also noticed an increasing appetite for 360 video. People are finally ready and interested in looking around places they cannot travel to. Looking at a video-on-demand model, Arnaud could see how Atlas V’s survival as a company could work if it shifts online and focuses on accelerating downloads. Of course, a major issue is that most would-be audiences do not have VR headsets. How could they encourage the adoption and distribution of personal VR headsets so people can watch VR content from home?

Arnaud notes that he fears for small, indie companies focused on location-based entertainment. Location-based entertainment is one of the major rising practices in the field. How will the experience of COVID shift the business model for teams working in this space? How can we as an industry support and uplift such experiences and indie distributors who will need help now to keep going forward?

Arnaud shared with me his personal conflicts about the mixed nature our industry. Immersive entertainment companies are the forefront of our virtual relationship with the world — both a solution for connection and a threat to natural resources. Humanity’s negative impact on nature has forced us to move towards an increasingly virtual connection. Our industry is financed by some of the biggest polluters on earth, from the energy consumed at data centers, to precious metals taken from the earth to create GPUs and CPUs, and the electricity it takes to power our systems.

Arnaud notes that he finds it a bit uncomfortable that so much of the success of his business and our industry relies on the collapse of nature. No more fish in the sea? No problem — we will just make a virtual aquarium where you can visit species of fish that we can no longer see in nature. At the same time, we are potentially inventing how people will discover and connect with the Earth through immersive entertainment and social VR platforms. The Covid-19 crisis is proving that people are turning to their devices for humanity and connection. Spaces such as social VR and virtual museums offer a way for people to discover and interact with culture and each other.

Kent Bye

Kent Bye is a journalist who hosts the “Voices of VR’’ podcast, featuring interviews with creators across immersive media — virtual reality, augmented reality, and artificial intelligence. Kent called me on Skype from his home in Portland, Oregon.

Kent has traveled around the world attending conferences and festivals, checking in on different local VR communities. With the COVID pandemic, he believes the golden era of VR conferences is over. For Kent, this means radically shifting the way he conducts his interviews and rethinking how to best share his work.

Last year Kent was asked by Sébastien Kuntz, the creator of VR teleconferencing software, why he doesn’t just interview his subjects in VR. Kent responded honestly, by sharing that he prefers face-to-face interviews. From fidelity to body language, he gets more out of speaking with people in person. VR doesn’t yet allow for the high-quality human interaction he believes leads to the best interview content.

According to Kent, two important elements have made physical presence at VR conferences so important: access to technology and social cohesion. You needed to be present there in the physical space in order to try the technology. For many years, if you didn’t attend conferences you had no other place to test out technical innovations. He suggests that we are now at a place where technology has stabilized and is becoming commercially available, thanks to devices such as the Oculus Quest, Mobile VR, and PC VR. While we once relied on those physical gatherings to share work, now we need to use technology that is available and get it into people’s hands in innovative ways.

Kent emphasizes that public screenings of VR during a global pandemic would be a nightmare. The public health implications of things living on surfaces, the difficulty of trying to demonstrate technology when maintaining a 6-foot distance from your audience, combined with the asymptomatic transmission of the virus all go to show that we need to steer clear of public VR displays for the foreseeable future. Even if you have the best protocols and safest cleaning practices, people would still not feel comfortable putting on a public headset.

The other key factor in the success of conferences is social cohesion, Kent says. When people sign up to attend a conference, they are committing to the magic of the event. They agree to be somewhere, fully, with their attention. They set aside whatever is happening in the rest of their lives. There are two main parts to conferences: one is the content of the conference (talks, sessions, and the technology demos and VR experiences) and the second is the hallway chatter, or what happens outside of those sessions.

These are the spaces for what Kent calls “serendipitous collisions.” A serendipitous collision is when he meets someone at an event in an unexpected way. A well-organized event should be designed to foster these collisions. When someone is fully committed to being at an event, they are likely to be open to possibilities, including conversations with strangers — collisions. Kent’s method for quantifying the magic of a gathering is whether a serendipitous collision leads to an interview for Voices of VR.

Kent is frustrated by the lack of serendipitous collisions in social VR spaces. He wonders if the global pandemic will force people to commit to the virtual worlds in a way that will push the limits of online interactions: Can we have these magic moments in virtual spaces?

I asked Kent if he’s one of those people who saves their badges from each conference. He isn’t. In fact, he loves the ephemeral nature of conferences and disposes of the badge following each conference as a personal ritual to signify the end of the gathering.

Kent believes that people will find new ways of having social events online, and bringing with them the ephemeral magic of physical conferences. A large role of festivals is curation, so maybe there will be new, decentralized curation opportunities for more individuals. He is fascinated by the opportunities we have now to translate face-to-face interactions to the virtual world. More conferences are making the jump into the virtual space: HTC had their ecosystem conference, GDC had twitch streams, and just this week, IEEE VR announced a venue change from Atlanta and moved the entire conference online.

Kent will be covering the conference from VR, just like he did in the physical world.

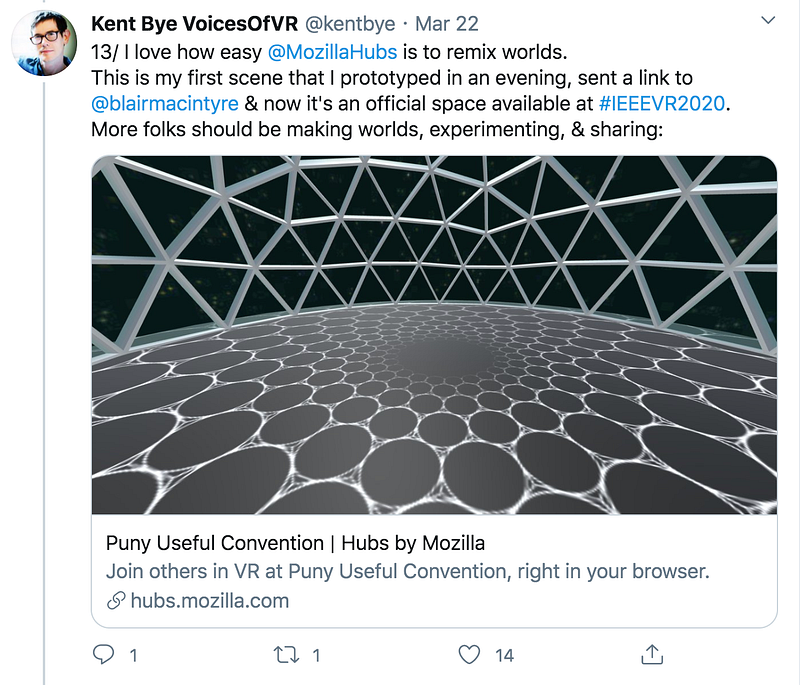

IEEE VR conference is using Zoom links as well as Mozilla hubs (virtual rooms you can hang out in with friends), and running its own server with open WebXR. Because it’s an open space, Kent is able to create his own world and actually put some of his own theories of experiential design into practice.

Screenshots from Kent’s room at the IEEE VR Conference in Mozilla Hubs.

Kent finds this switch from covering events to help build out the tools exciting and full of possibility. Suddenly, he is a participant, helping to tell the story of open web technology: how can people participate, how can people collaborate, and sharing how can we use these virtual social tools to experience social presence even when we are physically distant. Kent shares a running commentary of his experiences at the virtual conference on his Twitter account.

To examine the opportunities of moving conferences online Kent uses the SAMR framework. SAMR was created by Dr. Ruben Puentedura to measure the integration of classroom technology. There are four stages: Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, and Redefinition:

- Substitution: How do we replace restricted practices? For example, we used to host break-out sessions at physical conferences, so let’s move these to Twitch. Certain things can be substituted. But what about the social dynamics that cannot?

- Augmentation: What can be added to the existing model? Maybe there are things you can do slightly better, or do things you couldn’t do before? When attending virtual conferences, Kent now has the ability to be in two places at once. What does that mean? What else is added to our experience? You don’t have to travel, you can save time and money. You can do things more efficiently.

- Modification. How is the technology changing your design and what you want as your outcome? How can you reimagine what your goals are?

- Redefinition. You can completely redefine what is possible.

Now that so much of our lives are changing, Kent wonders how we can use virtual technologies to supplement life as we know it, and potentially augment and modify and completely redefine what is possible?

So what does this mean for the industry? “I think there’s a dialectic between the expansion and constriction,” he says. We’ve been in a very expansive phase to look at all the possibilities [of emerging tech] but now that we’re in a restrictive phase. It’s actually these constraints that can catalyze enormous amounts of creativity. For any artist, you know that working with constraints can be one of the most inspiring things for creativity. As a collective society we’re trying to inspire ourselves to see what we can do with all of these technologies.”

He wonders if he should redefine his own work. Over the last six years he’s conducted more than 1500 interviews from the golden era of conferences. Could he use virtual technology to create a museum people could visit? How should he distill the massive amount of information he’s collected? Should he roam around the open online world, reporting on what is happening in these virtual spaces?

Kent is supported by Patreon so he’s trying to figure out what would be of value to the larger VR community. He’s listening to what people want to learn about, what they want to hear about. For now, he’s focused on remote conferencing. While Covid-19 and social distancing create restrictions which disrupt our lives, he hopes the crisis might be a catalyst for the VR industry to create a sustainable future.

How has Covid-19–19 made an impact in your work? If you have a moment, please take time to respond to these impact surveys:

- Americans for the Arts — Impact Survey and list of relief funds.

- California Arts Council — For All California Arts Organizations and/or Individual Artists Directly or Indirectly Impacted: In announcing the statewide policy on mass gatherings, Governor Newsom stated “These changes will cause real stress — especially for families and businesses least equipped financially to deal with them. The state of California is working closely with businesses who will feel the economic shock of these changes, and we are mobilizing every level of government to help families as they persevere through this global health crisis.” The California Arts Council is surveying the arts field at large to gather data on the potential financial impacts of this public health emergency. If you are an organization or individual in the arts field that anticipates losing personal or business income related to Covid-19, please consider filling out the brief survey at this link. This is a quickly evolving situation and this data will be an important resource to inform our agency and the state.

Please be sure to check out the Immerse Covid-19 Resource list, and feel free to comment if you have any relevant information. We also invite you to join the Immerse Slack channel, where we will be discussing our experiences and offering peer support in the “howareyoucoping” channel.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and it receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing media projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.