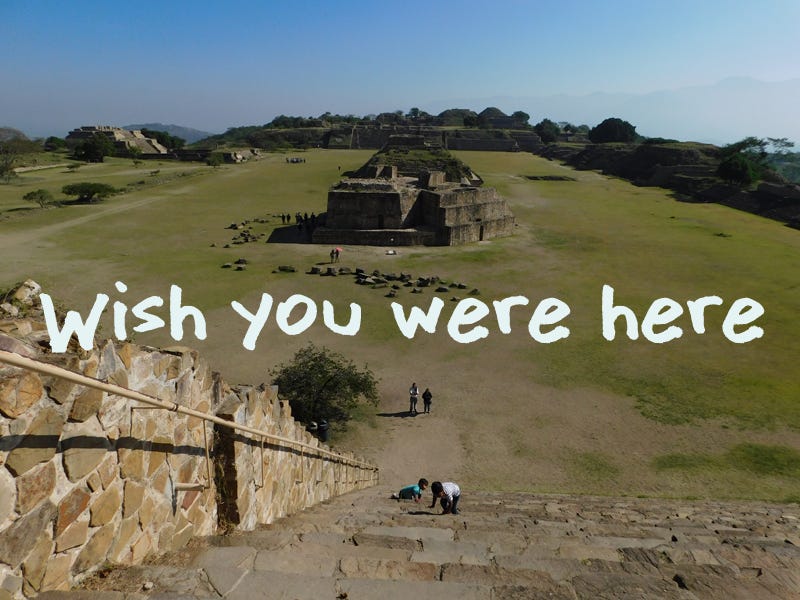

MONTE ALBAN, Mexico—Summer vacation 2018: I am staring at an obelisk, pondering my place in the universe.

Physically, I am incontrovertibly here, surrounded by pre-Columbian ruins, many engineered to interpret the movement of the cosmos from this precise spot on the planet.

Mentally, though, I am wandering through a haze of associations: other archeological sites I’ve visited while remaining keenly self-conscious of my own role as a tourist, the resonance of ruins as a trope for understanding our own evanescence, the way the bowl of the sky and the configuration of the stars once served to both situate and awe our predecessors.

It’s this twin feeling—of being both embraced and dazzled by the heavens—that VR film Biidaaban: First Light—taps into. Premiering at Tribeca Immersive, where I experienced it, the piece brings viewers into a future Toronto where nature is reclaiming the ruined city.

Beautifully executed, the room-scale VR rains down stars, which coalesce into words written in three First Peoples languages: Mohawk, Wendat, and Ojibway. These phrases prompt consideration of our relationship with nature, and our assumptions about linear history.

Charmed inside this imaginary scene, I wander to peer over the edge of a rooftop—and, jarringly, find myself inside a green-gridded matrix. Like Daffy Duck battling with his animator, or Truman sailing to the edge of his world, I’d come face-to-face with the boundary of this reality.

My confusion is further compounded when I remove the headset and exit into an antechamber which separates me from the main exhibit space. There I encounter a lone turtle in a lighted tank, staring at itself in a mirror. I photograph it, looking at itself, or perhaps looking at me looking at it.

I can tell from the text written on the wall that I am supposed to be contemplating my relationship with both language and nature—it reads, in part, “The original book is, of course, the world itself.” But at this moment I just feel a bit sad for the turtle, trapped in meta-commentary.

If Biidaaban: First Light brings the stars down to earth, another piece at this year’s Tribeca Immersive exhibition, Spheres: Pale Blue Dot, brings users up into the galaxy to witness the Earth’s origins.

This, too, is a tethered VR experience, which gives me freedom to roam a few steps as the Big Bang unspools around me, narrated by Patti Smith. The feeling of space here is vast, arid and lonely, emphasizing the beginnings of sound as well as matter. The installation where users stand is itself sterile—a smooth round room, painted white but coolly lit in a glowing blue. It strikes me a bit like the planetariums of old—grand and swooping but not emotionally gripping.

Space and sound are also married in Where Thoughts Go: Prologue. While the graphics in this VR experience are less sophisticated than many of the other pieces in this exhibition, its power lies in the intimacy of hearing others’ dreams and confessions, and the prospect of sharing your own.

Here, space is neither a friendly companion to our terrestrial journey, nor a mysterious void from which we came—but a symbolic backdrop, signaling our suspension in another world where users interact with animated orbs representing previous participants’ answers to intimate questions. The set of this installation, too, was different: a kind of harem tent, where you sit on cushions and snuggle into the interaction.

In the end, the projects that I found most intriguing at Tribeca this year weren’t the ones that evoked the celestial but instead created concrete spaces to explore here on Earth.

At first, Objects in the Mirror AR Closer Than The Appear just looks like the jumble of boxes that some of us might be trying to avoid in our own basements. Begin to poke through the piles with an augmented reality (AR) headset, however, and surprises begin to pop out.

“The piece is about our relationship to objects,” co-creator Graham Sack tells me. “The theatrical show that it was adapted from, The Object Lesson, is about people’s relationships to physical objects…and what we’ve done with this media exhibition is extend that to the digital realm. What we wanted to do with AR was give people an experience where they pick something up out of context in the environment and it suddenly becomes a jumping off point for a memory or a previous relationship.”

Part of what makes this interaction delightful is the array of whimsical AR headsets that users can choose from: a wooden box, a welder’s mask, an actual lampshade you wear on your head. “Because the exhibition is about our relationship to things, we wanted to make sure the viewers were themselves beautiful objects,” says Sack. “In working with our budget we discovered these 19th century stereoscopes that have exactly the same optics as modern viewer goggles. Using them was a way to juxtapose the bleeding edge of technology with its history.” Through these, participants can see, hear or explore digital experiences prompted by directing their gaze towards boxes or objects.

“Every asset is carefully curated, but there is a bit of a treasure hunt involved in terms of the user finding exactly what will trigger it,” says Sack. “The space is organized as an archeological dig, with a digital layer and a physical layer. We wanted to convey the sense that everything has the capacity to take us to another place.”

I stop in front of a painting with my headset and suddenly find myself inside of it. Sack explains that this 360 video has been altered to “create the appearance of a 19th century world. When you use it with the AR headset the painting comes to life and you break through the frame and are fully immersed in the scene.”

While this technology is not perfect, the ability to wander freely in the space and explore, and the familar junkshop feeling of snooping around other people’s semi-public memories does the trick. I feel for a moment engaged and transported, wrapped in someone else’s creation.

The same sort of logic applies to a more melancholy installation, Queerskins: A Love Story. Created by Illlya Szilak, the experience was inspired by her work in the 1990s as an AIDS doctor.

Participants are led through a re-creation of the attic bedroom of the story’s subject, Sebastian, a young gay physician who is estranged from his rural Catholic family and dies of AIDS. There, they experience a virtual ride to the cemetery in the backseat of a car with his conflicted parents, next to a virtual box of his belongings that they can comb through. Those same actual objects populate the installation space, where visitors are encouraged to pick them up, move them around, and be photographed with the one that moves them most for sharing on the project’s Instagram site.

“As a physician, I understand how embodied material, historical reality, is really important,” says Szilkak. “And there’s this human reach for transcendence — through art, through technology, through sex — but at the end of the day you’re going to take your VR set off and you’re still going to be gay or you’re still going to be black.”

Queerskins is striking in its range of both entry points and souvenirs. A poster-sized handout offers a map of the space, along with stats and resources about AIDS treatment. An online interactive narrative includes the diary, audio monologues, videos, and photos. Hand-crafted “take-aways multiples” provide participants with a poignant one-of-a-kind object to bring home—I choose a vintage postcard overwritten with text from Sebastian’s diary. Giving participants permission to move the props gives them a sense of authorship. As I leave, I reposition the contraband vintage Tom of Finland porn front-and-center, so that it is no longer hidden from the next visitor.

All of this is subjective, of course. Having a resonant physical space to explore is not necessarily the secret to more profound immersion. The physical does not always trump the digital.

Back at Monte Alban, I never do quite click in to the requisite sense of mystery and history. The ancient city is mostly empty, populated only by other early tourists and vendors selling reproductions of ancient gods and archetypes. The narrative of the site feels closed, already written. The sense of local particularity is diluted by the global visual language of explanatory plaques.

So, I dutifully do my part to steal one more sliver of the site’s aura, by transmuting the space into digital memories.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund, and is fiscally sponsored by IFP. Learn more about our vision for the project here.