Surveying recent social media archives of street projections that subvert official narratives in South America

In November 2020, Peru — which already had been one of the countries most affected by the pandemic and the global economic crisis — experienced a moment of extreme political instability, leading to the impeachment of then president Martín Vizcarra. This sparked a massive wave of civil unrest, as it was seen as a coup orchestrated by the opposition forces in the parliament.

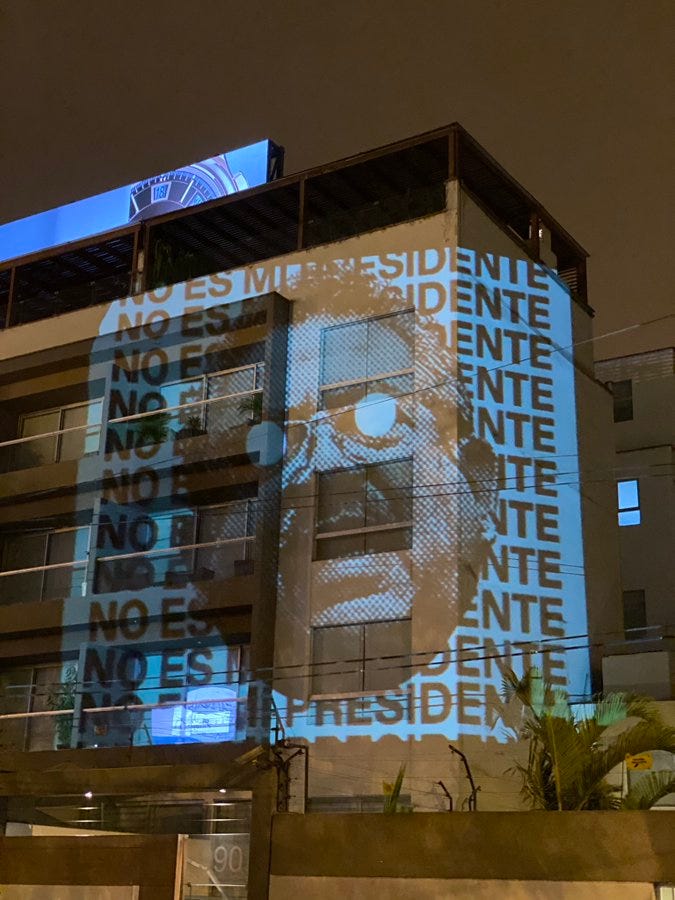

As the crisis unfolded, the use of a particular tactic stood out: street projections. Ingenious protesters reached the house of Manuel Merino — Vizcarra’s replacement in the presidential palace — to tell him that he was not their president, making clear that they wanted him out of office. This tactic also targeted TV stations, which were deemed to be accomplices of the illegitimate regime for their negative portrayal of the people marching in the streets.

Projection in Manuel Merino’s house. Translation: “Not my president.” Lima,

Peru. November 13, 2020. Source: https://twitter.com/helloketty_pe/status/1327448773749051392

Projection in Manuel Merino’s house. Translation: “Not my president.” Lima,

Peru. November 13, 2020. Source: https://twitter.com/helloketty_pe/status/1327448773749051392

Tragically, during the night of November 14th, two young protestors — Inti Sotelo and Jack Bryan Pintado — were killed by the police. The morning after, Merino stepped down from government after five catastrophic days in office. Activists continued to project statements, but now they had a different tenor. Projections were no longer a tool of protest. Projections now were a tool of memory: to memorialize the deaths of those who valiantly confronted an illegitimate regime.

Projection in the streets of Lima made by artist Claudia Coca. Translation:

“His name was Inti like the sun and the sun never fades out” [TN: inti means sun in Quechua].

Lima, Peru. November 16, 2020. Source: https://twitter.com/jfowks/status/1328503859308867584

Projection in the streets of Lima made by artist Claudia Coca. Translation:

“His name was Inti like the sun and the sun never fades out” [TN: inti means sun in Quechua].

Lima, Peru. November 16, 2020. Source: https://twitter.com/jfowks/status/1328503859308867584

Luminous interventions have been gaining ground globally in recent years for multiple purposes. However, artists and activists in Latin America seem particularly keen to employ projections as a remembrance of historic political episodes. This has been the case in Chile, where the 2019 and 2020 protests employed projections to remember the cases of human rights abuses committed by their military and police. Similarly, in Argentina projections bring back the faces of the desaparecidos of the military dictatorship. In Brazil, activists remember fallen fellows, recent victims of violent right-wing extremists.

The affordances of projections certainly offer two prominent advantages: portability and spreadability. First, in contrast with other expressions such as graffiti and posters, the message of the projections is not fixed to the support (e.g. walls). So, as long as one can move the necessary devices around the city, the same message can appear in different spaces and/or at different times. The file containing the message can also be distributed to different individuals with adequate equipment and, with enough coordination, the message can be projected in different places simultaneously. But whereas graffiti and posters remain in their places until they are taken down, projections are only visible while the device is on. Paradoxically, the messages compelling us to remember fade when the light goes off.

Mobile

artistic intervention by artist Juan Castillo. Translation: “We demanded dignity and they

declared us war.” Valparaíso, Chile. March 3, 2020. Source: https://www.instagram.com/p/B9UHsRtJS1E/

Mobile

artistic intervention by artist Juan Castillo. Translation: “We demanded dignity and they

declared us war.” Valparaíso, Chile. March 3, 2020. Source: https://www.instagram.com/p/B9UHsRtJS1E/

Social media users have worked their way around this issue. The custom of capturing and posting remarkable moments or events have created — sometimes inadvertently, others purposely — an archive of these luminous manifestations, storing their message in a more stable form: bytes in a database. Here the message acquires a second layer of spreadability. As publications are shared, the message reaches new persons: these memories are now not only available to those who witnessed a projection in a public space as it was happening but also to those who come across a post on social media.

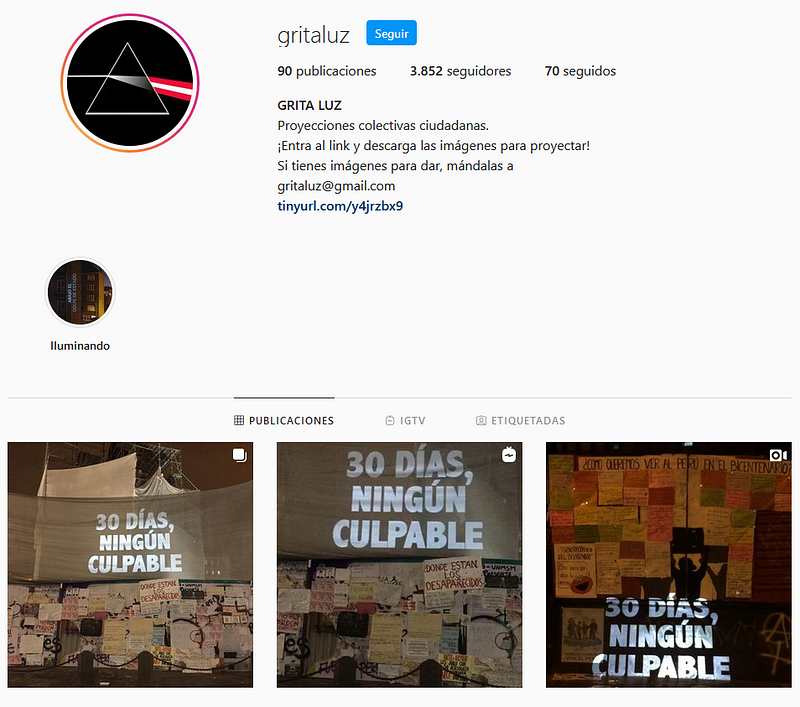

Screenshot of the Instagram feed of project gritaluz, Peru. Bio: “Collective

civic projections. Follow the link and download images to project. If you have images, send them

to [email address].” The projected text in the three images at the bottom: “30 days, no one

guilty.” Source: www.instagram.com/gritaluz/

Screenshot of the Instagram feed of project gritaluz, Peru. Bio: “Collective

civic projections. Follow the link and download images to project. If you have images, send them

to [email address].” The projected text in the three images at the bottom: “30 days, no one

guilty.” Source: www.instagram.com/gritaluz/

Certainly, these platforms have their own high dose of ephemerality. As any social media user knows, there is a propensity to quickly jump from one topic to another. Without any indexation or curatorial labor, these images of messages fade away when the projector is turned off. Fortunately, there are users dedicated to preserving these images in dedicated social media accounts. By storing, curating, and indexing these shareable images, these users create what we could name as spreadable archives.

Examples of these practices of archiving can be found in different platforms, although Instagram seems to be the preferred choice. For instance, Coletivo Projetação from Brazil is a long-standing collective that started in 2013 and does projections on a wide range of topics — from anti-racism to abortion legalization. A much more recent initiative is La Nueva Banda de la Terraza from Colombia, which started in 2020. Under their motto #aisladosperonocallados (#isolatedbutnotsilent), they started making projections as an alternative way of protesting during the COVID-19 pandemic.

These archives are not free of complications such as ownership. These platforms are owned by corporations and there are no publicly owned alternatives. As a consequence, the registers of all these messages invoking the public memory are ironically privately owned. They do not belong to the public and our access to them can change according to corporate decision-making processes. The luminous messages that moved across an open public space, once turned into digital images, now circulate through private digital infrastructure.

Besides these general technological issues, Peru has its own complex relationship with historical memory. After the period of internal conflict during the eighties and nineties, the transition government of Valentin Paniagua in 2001 organized a Truth Commission in charge of clarifying the crimes and human rights abuses committed during these decades. The commission produced a detailed report composed of nine volumes. Given the evident impracticality of such work for dissemination purposes, an abridged version of the report was produced. Still, this version was more than 500 pages long. An even briefer publication containing only the conclusions of the report was also produced. Other alternatives, such as comics focusing on particular events, were also published.

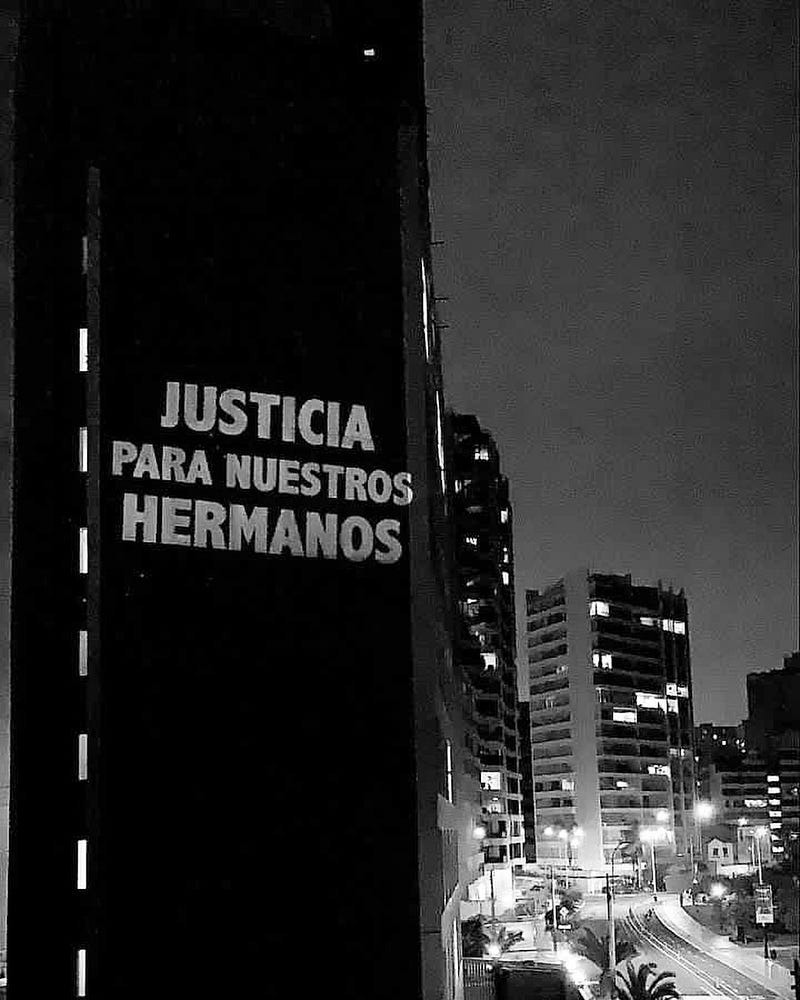

Projection in the streets of Lima. Translation: “Justice for our brothers.”

Lima, Peru. November 29, 2020. Source: https://www.instagram.com/p/CIMqWBfpVo-/

Projection in the streets of Lima. Translation: “Justice for our brothers.”

Lima, Peru. November 29, 2020. Source: https://www.instagram.com/p/CIMqWBfpVo-/

Written accounts of our collective memory are still necessary because they stabilize narratives. Over the centuries, the book as a media form has been fundamental for the dissemination of information. People also share and discuss what they read. But, unlike the projections highlighted in this piece, with books information consumption happens primarily between one person and one object. Furthermore, the fact that Inti and Jack died as a result of recent state-sanctioned violence complicates the production of official media memorializing them. In contrast, public projections have been mostly led by artists, activists, and common citizens.

Projections in public spaces do not replace expressions in other media forms. What they offer are new possibilities for how memories can be told and retold. They move memories out of books or museum exhibitions and into the streets. In this sense, it could be said that projections in these spaces make memory truly public. Moreover, their ephemerality also reminds us of the continuous labor that memory requires. Names, events, and ideas that are not mobilized are destined to wither. It is up to each one of us to bring them back. Let us not forget.

For more news, discourse, and resources on immersive and emerging forms of nonfiction media, sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Immerse is an initiative of the MIT Open DocLab and receives funding from Just Films | Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. IFP is our fiscal sponsor. Learn more here. We are committed to exploring and showcasing emerging nonfiction projects that push the boundaries of media and tackle issues of social justice — and rely on friends like you to sustain ourselves and grow. Join us by making a gift today.